[two_third]

Lesson 2

Attending to the Breath

In our second lesson, we again bring mindful awareness, mindful attention, to the breath. To pay attention to, to attend to something is a fundamental human experience that can be practiced and refined. I am always telling my son that if he keeps his attention focused on his homework he will finish in half the time it would take him than it would if he keeps spacing out when a challenging problem arises.

But the mind does wander, does space out, does become distracted, especially when confronted with a new challenge, something unfamiliar, something that does not have pre-created neural pathways it can refer to. The 6th limb of Patanjali’s 8 limbed path of yoga is dharana, a nice Sanskrit word for the practice of bringing the mind back to the point of attention, again and again, again and again. Knowing ahead of time the mind becomes distracted, we have a goal, a plan, a mental suggestion to return the attention to our chosen focus. This takes discipline (tapas), will power, effort. This is the beginning of spiritual practice. Patanjali introduces the term abhyasa, the practice of stabilizing the mind as his first discipline in Chapter I on the Yoga Sutras.

What begins as a disciplined reminding to stay focused gradually becomes a continuous sustaining of attention. This state is the 7th limb of Astanga Yoga, dhayana, which is the Sanskrit origin of the word Zen in Japanese. Implied here is the continuing tapas, the effort to resist the habituated state of restlessness and sustain attention. It is a more advanced state than dharana as the discipline has become stronger than the conditioning, but the conditioning is still lurking in the background, waiting to resume its restless or dull behavior if the discipline breaks down. Eventually there is a shift in the nervous system, the disciplined attention becomes the normal state, the restlessness subsides and the attention is sustained effortlessly. This is the 8th of Patanjali’s limbs, samadhi, remaining the same (sama), unchanging, relaxed awareness. Tough grader that he is, Patanjali calls samadhi the beginning of yoga.

Various schools of spiritual practice use different focal points to cultivate concentration, another term for focal attention. Some yogis use a mantra, a short Sanskrit prayer repeated over and over in a practice known as japa. Some Zen Buddhists use a mind puzzle, known as a koan to hold the attention. Some Tibetan Buddhists build complex visual pictures in their mind, over months and years.

Almost universal in spiritual practices across cultures is the use of the breath as a crucial anchor for attention and it will be ours for the whole of our adventure together. The breath, (spirit…spiritus is the Latin word for breath…, prana, chi or ki) is the ongoing expression of our innate living energy, our fundamental aliveness, replicating the primary cosmic rhythm of expanding and condensing, yang and yin, we find in stars and galaxies, in our cells and organs. As we will experience directly, our breath is the source of all of our actions, all of our perceptions, and we will return to the breath again and again in all of our practices.

Feeling the Details of the Breathing Process

On a gross level, the breath is the air moving in and out of the lungs.

On the subtle level, breath is the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide from the cells, the blood currrent, and the lungs, as well as all of the energetic actions that arise from the cellular processes, including respiration, circulation, digestion, growth and development of new structures and the dissolving of unwanted structures. The causal breath is the cosmic life force itself, the animating presence of aliveness.

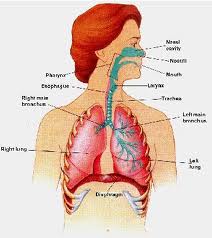

To begin, just notice the fact that you are breathing. Feel the rhythmic structure of the process. There are two opposite movements in every cycle of breath; inhalation brings air into the lungs, exhalation removes air from the lungs. We can imagine a pendulum oscilating back and forth, and, like in a pendulum, in the breathing cycles there are also pauses or moments when the movement comes to a natural state of rest. At the end of inhalation and before exhalation there is what is usually a very brief pause. At the end of exhalation and before inhalation is what is often a slightly longer pause. These pauses are also moments when the breath can be held or restricted and thus these are very important moments to be alert. Read the science section on the anatomy and kinesiology of respiration so you can begin to visualize the diaphragm, the ribs and intercostal muscles and the abdominal wall. This will help bring the sensations of these structures and their movements to your conscious awareness and help you track the flow of breath in deeper way.

Homework: For the next 24 hours, whenever you remember, check in on the breath and notice how often you hold your breath, how often those pauses become constrictions to the flow of your breath. Do not be shocked when the number seems large. Find out how to release the breath in a relaxed way when you find yourself holding on. What you will discover in time is that the restlessness of the mind and the restricting of the breath are directly related. If you look deeply, you might begin to notice where in the body the holding takes place. The diaphragm and ribs are the obvious areas to notice, but also consider your throat, your spinal column and your neck and shoulder muscles.

In your yoga practice, let your intention to feel the breathing be primary. All other instructions require the continuous flow of breath. If you hold or restrict the breath for any reason, the nervous system is receiving the wrong information about the pose. Too many students sacrifice the breath to ‘go deeper’ into postures. Within the practice of the yoga postures, new sensations, new positions, tightness in the muscles, and other factors will conspire to constrict the flow of the breath. Yoga requires the breath to flow. If you are holding your breath, it is not yoga! (Even the retentions of pranayama are not restricting the pranic flow. There is only a cessation of the outer form of the breath. The subtle breath continues to flow freely and easily, when pranayama is practiced safely and correctly).

When practicing the postures, remind yourself again and again, keep breathing, keep the breath flowing, do not hold the breath. As we go deeper in the practice we will discover many different ways to use the breath as the primary focus, but as a beginner, you may find yourself lost in the structural instructions: extend your leg, bend you knee, turn from the trunk, tuck the pelvis etc etc. Tight muscles, collapsing chest and constricted thinking all impede the free flow of breath.

Make sure the breath is an integral part of your own self-talk during your practice. Don’t worry that this can be challenging in the beginning. It will become effortless in time, but the discipline is crucial.

In the next practice theme, “Grounding”, we will discover a way to expand our sense of breath, connecting the diaphragm, through the legs and feet into the earth.

[one_third_last]

Beginning: Related Links

1. Developing Mindful Awareness

2. Attending to the Breath

3. Orienting to Grounding and Lightness

[/one_third_last]