Lesson 3:

Orienting to Weight and Lightness

We continue bringing mindful awareness to the breath, to the moment and now we bring our focal attention to the felt sense of weight and the felt sense of lightness in the body. Amazingly enough, before we can pay attention to, attend to anything, we have to first, consciously or unconsciously, orient ourselves to gravity and then the space around us. We need to locate ourselves in the world. Only then can we make sense of the myriad sensations that are bombarding the nervous system moment by moment, can we isolate one group of sensations and inhibit or diminish the others. If, in your travels, you have ever woken up in the middle of the night in a strange bed, you may remember the disorienting state while the mind tries to answer the question “Where am I?”. From the point of view of the nervous system, ‘where?’ is an on-going enquiry.

The fundamental orientation of the body is down, to the earth, to gravity and the felt sense of weight. The first cranial nerves to myelinate during fetal development are the vestibular nerves. These innervate the vestibular system, the series of bones, tubes and fluids in the inner ears that give us a felt sense of a stable ‘down’ and the corresponding capacity to orient to the space around us.

In “The Brain That Changes Itself”, there is an amazing story of a woman who had sustained damage to her vestibular sense and constantly had the sense of falling. Even lying on the floor, her embodied experience was that of falling. Her vestibular sense could not find ground. A pioneering neuro-scientist devised a helmet which sat on her head to recreate the vestibular information. This was connected to a sensor on her tongue, (an extension of the nervous system), to feed the brain with this information. By practicing with this sensor, she gradually reprogrammed her nervous system, weaned herself off of the helmet, and, through her tongue, restored her innate sense of balance and stability.

The complimentary orientation is to space and the felt sense of lightness. How do we experience the space around us, including the sky above us, and the beings, objects and sets of conditions that occupy this space. In order to move through the world, we need to make sense of where things are in relation to how and where we are moving, or else we will keep bumping into or tripping over things. In earlier times, this skill was crucial in finding food and avoiding danger.

Because the human nervous system does not emerge fully formed, (see the Neuroscience section) some developmental aspects can need extra help in becoming integrated, and this fundamental orienting system is one of them. Now a days there are many children who are diagnosed with various degrees of “sensory integration” dysfunction and my son Sean happened to be one of them. ” Sensory integrative dysfunction is to the brain what indigestion is to the digestive system.” Although this is a complex subject, this essentially means that their nervous system has difficulty processing sensory information and this will in turn affect activity and behavior.

My son was hypersensitive to many sensations coming from the world around him, but very insensitive to the sensations coming from his own body. As an example, when he was in kindergarten, he just could not ignore the random sounds coming from the heating pipes from the floor below, thus could not pay attention to what was going on in class, and would often get in trouble with the teacher for not cooperating. On the other hand, because he could not feel his own body, he would often push or poke other kids to increase his own physical sensations, to ‘find himself’, to help orient himself to the room. As we discovered, these are classic signs of SI dysfunction and we had him evaluated to learn more about what could be done to help. He was not intentionally being a trouble maker, but was struggling trying to organize his nervous system to handle the complex environment of the classroom.

One of the primary therapeutic interventions introduced for Sean was to have him add weight to give him a stronger sense of ground to help find where his body was in space. We had a weighted vest for him to wear, sand bags to put on his legs when sitting, and had him push against heavy objects to increase the feedback of his muscles and bones. His teachers were asked to give him tasks such as carrying stacks of books, even push-ups when he seemed to be distracted.

What fascinated me was that I had been doing such things for myself in my yoga practice for many years. The Iyengar system had taught me how to carefully use sandbags and barbell plates to weigh down the legs, arms and other parts of the body in specific supported poses.  My experience has always been feeling the muscles slowly relax as a surrendering shift of the weight into the bones and from the bones to the gravity and the earth. In the integrated state there is a simultaneous feeling of both weight and lightness. But until Sean’s challenge, I had never realized the deeper implications of a deeply felt sense of weight, felt sense being the operative phrase here. My body has weight and is being supported by the earth. I can relax, and my whole nervous system shifts gears!

My experience has always been feeling the muscles slowly relax as a surrendering shift of the weight into the bones and from the bones to the gravity and the earth. In the integrated state there is a simultaneous feeling of both weight and lightness. But until Sean’s challenge, I had never realized the deeper implications of a deeply felt sense of weight, felt sense being the operative phrase here. My body has weight and is being supported by the earth. I can relax, and my whole nervous system shifts gears!

Eight years later, Sean is very embodied, active in sports, and much more (relatively speaking!) relaxed. He was never interested in soccer (needed to be grounded in his legs) but very interested in baseball, swinging and throwing with his upper body. He finally found his legs through the surprisingly demanding discipline of fencing and it is amazing to see how his personality and self confidence grew by the day with his practice. He can feel his own embodied strength and actually continue to increase his own self integrating capacities. Today he is a serious hiker and kayaker, and does weight training and running. This whole process has been hugely influential in my understanding of how the yoga poses can be utilized to accelerate our own continuing integration process.

Tadasana

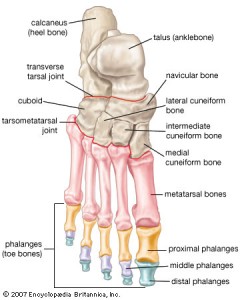

We humans, as bipedal creatures, rely tremendously on our feet to be the energetic link from our nervous system to gravity. Our feet, all 52 bones of them, provide the foundation for integrated body movements and the key to understanding the nature of the upright posture. For an untrained body, the feet are a place of tension, confusion and suffering. Plantar fasciitis, ankle sprains, achilles tendon problems, and bunions are just some of the challenges that are felt in the feet. In yoga, we learn how to use the feet wisely, how to distribute the flow of support through all of the bones into ground. (Feet as Tensegrity Structures)

In this course, we are going to use the skiers pose for tadasana, our staring point of exploration. In skiing, (or ice skating, snowboarding, skateboarding, roller blading etc) the knees are relaxed and slightly flexed to allow the felt sense of ground to come into the feet. You would never try to ski with straight legs because you lose resilience and connection. Why should a yoga pose be different? As the body learns to relax downward into the feet, and beyond the feet into the center of the earth, there is a felt sense of balance and flow. Even though there is no obvious outer movement, as in skiing, the ease of relaxed balance remains, and we discover balance involves non-stop micro-adjustments and subtle movements. Visualize a tight-rope walker sustaining balance. This is the crucial reference for all of our yoga postures. Can I feel relaxed, fluid and grounded.

A deeper look at feet offers us more insight into posture.  From standing we begin to move and we use our feet to initiate movement. Both walking and running involve the feet having a dynamic relationship with the ground underneath us. How we push off determines the speed and direction of our movements. Take a walk around the room noticing your feet. What parts of your feet do you feel? Where is your weight? What happens with the heels, the arches, the toes? Stop and pause again in tadasana

From standing we begin to move and we use our feet to initiate movement. Both walking and running involve the feet having a dynamic relationship with the ground underneath us. How we push off determines the speed and direction of our movements. Take a walk around the room noticing your feet. What parts of your feet do you feel? Where is your weight? What happens with the heels, the arches, the toes? Stop and pause again in tadasana

An important insight arises if we are attentive. We never lift our arches to move! On the contrary, we push down through the arches into the earth to create a springing rebound that propels us through space. Visualize skiing or skating and how you push down through the edges/blades to create movement. This is fundamental and very much misunderstood in the yoga world. so many teachers ask student to lift their arches to wake up the feet. While it is of utmost importance to awaken the feet, lifting the arches actually hardens them, makes them less elastic, and blocks the healthy flow of grounding energy necessary. All yoga postures are expressions of natural movements that the body does. If you cannot get into and out of a yoga pose fluidly, you do not belong there! All beginners should learn how to move in and out of postures easily before staying longer in them. Do not “hold” postures, but sustain them like a singer will sustain a note. No constrictions or dullness, no rajasic or tamasic activity, but a balance of stability and mobility to sustain the pose.

Next we will look at going into and coming out of postures as we look to sustain this felt sense of balance at all times.

.