[two_third]

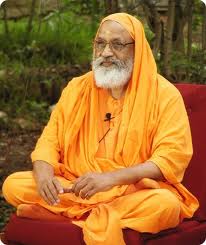

Overview of the Bhagavad Gita ( Based on Swami Dayananda’s home study course )

( Based on Swami Dayananda’s home study course )

The Bhagavad Gita, one of the oldest and most profound articulations of spiritual awakening in human history, is a story within a story. Vyasa, an ancient sage, poet and historian enfolds the story of Arjuna’s confusion and Krishna’s teaching into the epic poem The Mahaabhaarata which is centered around a large battle between two factions of the royal clan of the Kurus. It is a classic story of good versus evil, of right versus wrong, with plots, sub plots twists and turns, culminating an a great battle scene. The bad guys are organized around the 100 sons of Dhrtaraastra. The good guys center around the 5 sons of Paandu, the Pandavas, one of whom is Arjuna.

As the Gita begins, the armies are facing each other, awaiting the beginning of the battle. Krishna, the Divine one overseeing the battle could not take sides, so he offered a deal to the leaders of the two armies. One could have his vast army, the other could have him as a charioteer, although he would not fight. Arjuna chose to have Krishna, and Duryodhana, the opposing leader, was delighted to have Krishna’s army. Arjuna asks Krishna to take his chariot to a place where he might see all of those whom he would be fighting. Upon recognizing relatives and revered teachers among the enemy army, Arjuna falls into a great despair. Krishna’s teachings begins at this point.

Krishna, the Divine one overseeing the battle could not take sides, so he offered a deal to the leaders of the two armies. One could have his vast army, the other could have him as a charioteer, although he would not fight. Arjuna chose to have Krishna, and Duryodhana, the opposing leader, was delighted to have Krishna’s army. Arjuna asks Krishna to take his chariot to a place where he might see all of those whom he would be fighting. Upon recognizing relatives and revered teachers among the enemy army, Arjuna falls into a great despair. Krishna’s teachings begins at this point.

One of the foundations to understanding the Mahaabhaarata concerns the Vedic teachings on the human condition, the four purushaarthas or the fundamental pursuits of all human beings. These are:

Artha: security

Kama: pleasure

Dharma: joy or satisfaction in doing what needs to be done

Moksha: (freedom from all wanting and insecurity, enlightenment).

The teachings of the Mahaabhaarata center around upholding dharma and in the Gita, Krishna’s teaching to Arjuna expands this into upholding dharma plus moksha, or total freedom from suffering.

All human beings pursue artha and kama, security and pleasure. Security may be very basic: food and shelter. It may be financial, in the form of money, real estate, stocks and bonds; social in the form of power, education, a title; physical with a guard dog, burglar alarm, or karate lessons; emotional security is sought in relationships and spiritual security can be sought in religion or belief systems.

Pleasures of all sorts are also pursued. Sensory pleasures include the obvious food and sex, but also physical activities such as skiing, hiking, basketball and other sports. Intellectual pleasures may include reading, puzzles and games, discussions and debates. Emotional pleasures are derived from following a sports team. Aesthetic pleasures such a music, art and nature are also desired and desirable to all.

If we observe ourselves, we will notice how large expenditures of energy and time are devoted to these first two pursuits.

Dharma is a Sanskrit word with many layers of meaning. Here it refers to a pleasure different from artha and kama. It is not based on acquiring or achieving anything but rather on being friendly, compassionate, honest and trustworthy. It is the delight in gratefully doing what needs to be done. There is an inherent joy in being nice and at some point in our maturing, this becomes even more desirable than security and pleasure. In fact we can say that becoming more mature is awakening to the role of dharma in our lives and living more and more in conformity with it.

As maturing beings we can now re-prioritize our pursuits: dharma, atha and kama. Without violating dharma, we are free to pursue security and pleasure. This is the way an intelligent society self organizes, and without the concept of dharma as a guide, the pursuits of security and pleasure can lead to much suffering. The concept of dharma plays a large role in the Gita as we will later see.

Moksha is the most important of the purushaarthas but is rarely recognized in human societies. Perhaps a few wise ones in any given generation will have the maturity and wisdom to recognize the subtle and not so subtle dead ends hidden in the previous pursuits. Moksha means freedom from being a wanting person, freedom from wanting or desiring to be different, freedom from a lack of self acceptance. Moksha is freedom from seeking itself. Krishna’s teaching to Arjuna is, in Vedantic language, brahma vidya, knowledge of Brahman, a term which signifies wholeness, fullness, The divinity plus creation, the world of time and space and the times unbounded source out of which creation appears and into which it (including time and space itself) dissolves.

As Krishna points out, this wholeness is the Truth of ‘I’, of everyone, but most believe themselves to be limited, small, wanting and thus suffer struggling to overcome this confusion. It takes 18 chapters to unfold the simplicity of this, as confusion arises continuously in the seeker. Part of Arjuna’s confusion involves the differences between two approaches to acquiring this wisdom, the path of knowledge known in India as sanyaasa, and the path of action, karma yoga. He feels that sanyassa, which involves dropping out of society and leaving behind all social obligations, is the only path to self knowledge. Krishna’s teaching goes into depth as to why karma yoga is an equally valid path, if understood, and that moksha is available to anyone, not just the renunciates.

Although we will not study each chapter in depth, I recommend you go through the whole 18 chapters several times to get a feel for the approach Krishna takes. Find a translation that speaks to you. Find verses that speak directly to your heart. The one I first discovered in 1971, the Penguin Classic translated by Juan Mascaro, is very simple, (120 pages), beautiful and rich. Swami Dayananda’s home study course has four 500 page volumes. Stephen Mitchell, translator of the Tao Te Ching (and husband of Byron Katie, an Ojai neighbor ) has a new translation out, but I have not seen it yet. This web site will focus on a few key verses to help in the understanding and we will tie these into to other teachings and the study course. Everything here is based upon the brilliant expositions of Swami Dayananda, my primary teacher for the Gita and other Vedantic teachings as well as the Yoga Sutras. Om tat sat!

|

|

[/two_third]

[one_third_last]

Related Links

Essential Verses of the Gita

Yoga in the Gita

Sthita Prajña (Stable Wisdom)

Summary of the 18 Chapters

[/one_third_last]