I love the circularity, or pehaps the cyclicality of the universe.  I have been immersed in a Taoist phase of practice for quite a while now, exploring all levels of reality through the lens of embodiment (spirit becoming flesh) and the yin/yang polarities of the cosmos. (By the way, Patanjali is also a Taoist. The very first practices he introduces, early in the Samadhi Pada come as a pair, abhyasa and vairagya. He also refers to the dvandvas, the pairs of opposites, in Sutra II-48, his third sutra on asana.)

I have been immersed in a Taoist phase of practice for quite a while now, exploring all levels of reality through the lens of embodiment (spirit becoming flesh) and the yin/yang polarities of the cosmos. (By the way, Patanjali is also a Taoist. The very first practices he introduces, early in the Samadhi Pada come as a pair, abhyasa and vairagya. He also refers to the dvandvas, the pairs of opposites, in Sutra II-48, his third sutra on asana.)

Back in my college days, I was introduced to the I Ching, also known as the “Book of Changes” by Huston Smith in his class on Eastern Spirituality and for several years after I immersed myself in exploring the radical wisdom unfolded in the I Ching. On a shamanic adventure in Sedona Arizona a few years ago I was reintroduced to the hexagrams and had an immediate re-awakening to its importance to the somatic explorations in my practice. I recently pulled out my old copy from college, started some enquiries and have been further blown away by how alive, dynamic and relevant it is! I decided to do a blog post on the basics of I Ching, and asked the I Ching to comment on my decision.

I Ching, also known as the “Book of Changes” by Huston Smith in his class on Eastern Spirituality and for several years after I immersed myself in exploring the radical wisdom unfolded in the I Ching. On a shamanic adventure in Sedona Arizona a few years ago I was reintroduced to the hexagrams and had an immediate re-awakening to its importance to the somatic explorations in my practice. I recently pulled out my old copy from college, started some enquiries and have been further blown away by how alive, dynamic and relevant it is! I decided to do a blog post on the basics of I Ching, and asked the I Ching to comment on my decision.

I will explore the answer in a minute, but want to mention that in reading the introduction to get some background info, I found that Carl Jung,  when asked to write a preface to Richard Wilhelm’s famous translation, (and the one I use) had a similar idea. He asked the I Ching to comment on his idea of presenting the I Ching to the Western mind. I will include the answer he received a bit later as well.

when asked to write a preface to Richard Wilhelm’s famous translation, (and the one I use) had a similar idea. He asked the I Ching to comment on his idea of presenting the I Ching to the Western mind. I will include the answer he received a bit later as well.

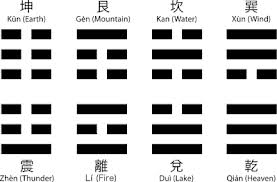

It is difficult to explain the I Ching to Westerners as there is no obvious correlate in either Western spirituality or science. The modern world tends to see a universe of independent, or even isolated causality. The I Ching emerged from an understanding of absolute wholeness or interconnectedness, at every level, at all times. Dating from as early as 1000 BCE, the hexagrams are essentially ways to explore how your sub or unconscious is aligned with the fullness of what is unfolding in the present moment. As the universe is in constant motion, life conditions are constantly changing. Is it time to move, or time to wait? Move with caution, with joy? Many layers and nuances are enfolded into the teachings of the I Ching, allowing you to have a cosmic perspective on decisions or choices you may be making and on the overall dynamics of the natural world. The I Chng immerses you in a world of fire, water, earth and wind, of safety and danger, of growth and decay, of teaching and learning, leading and following, of fundamental creativity and fundamental receptivity.

You approach it by first asking a question, then building a hexagram composed of 6 lines, each either yin (divided) or yang (solid) and finally reading the commentaries that accompany that hexagram in the book. The hexagram is seen to be composed of 2 trigrams, each representing an aspect of the natural world, the seasons, or the mother, father, 3 daughters and 3 sons. There are 8 possible trigrams, 64 possibles hexagrams.

The interpretation of the hexagrams in the I Ching involves both comparing the two trigrams and their aspects to each other as well as the relationship of each line to each other line.

The classical approach to constructing the hexagram uses either a bundle of 49 yarrow stalks or three coins. Using coins are easier to explain. Heads are assigned the yang number 3, tails the yin number 2. The coins are shaken and tossed and the sum is calculated. Three heads gives 9, three tails gives 6. These lines are called old yang and old yin. They are known as moving lines and add relevance in the commentary. The sum can also total 7, young yang, or 8, young yin. These young lines are static and do not invite further commentary. The first line is the bottom line of the hexagram and you build up to line six at the top.

In asking the I Ching about my presenting it in the blog, I threw 8, 7, 8, 6, 6, 9, corresponding to hexagram at the left. This is called Mêng / Youthful Folly and is addressed to students and teachers. (Uncanny is a good word!) The upper Trigram is Kên, Keeping Still, Mountain; the lower trigram is K’an, The Abysmal, Water. The commentaries following come from the edition of the I Ching shown above, Bollingen Series XIX from the Princeton University Press.

“The Judgment: YOUTHFUL FOLLY has success. It is not I who seek the young fool; The young fool seeks me. At the first oracle I inform him. If he asks two or three times, it is importunity. If he importunes, I give him no information. Perseverance furthers.”

(my commentary: The I Ching waits for students to come. It is happy to answer an honest question. But it won’t waste time on foolishness.)

“Commentary: In the time of youth folly is not an evil. One may succeed in spite of it, provided one finds an experienced teacher and has the right attitude toward him. This means, first of all, that the youth must be conscious of his lack of experience and must seek out the teacher. Without this modesty and this interest, there is no guarantee that he has the necessary receptivity, which should express itself in respectful acceptance of the teacher. This is why the teacher must wait to be sought out instead of offering himself. Only thus can the instruction take place at the right time and in the right way.

A teacher’s answer to the question of a pupil ought to be clear and definite like that experienced from an oracle; thereupon it ought to be accepted as a key for the resolution of doubts and the basis for a decision. If mistrustful or unintelligent questioning is kept up, it serves only to annoy the teacher. He does well to ignore it in silence, just as the oracle gives one answer only and refuses to be tempted by questions implying doubt.”

The Image: A spring wells up at the foot of the mountain: The image of youth. Thus the superior man fosters his character by thoroughness in all that he does.”

The Lines: Six in the forth place means: Entangled folly brings humiliation. For youthful folly, it is the most hopeless thing to entangle in empty imaginings….Often the teacher, when confronted with such entangled folly, has no other course but to leave the fool to himself for a time, not sparing him the humiliation that results….

Six in the fifth place means: Childlike folly brings good fortune. An inexperienced person who seeks instruction in a child like and unassuming way is on the right path, for the man devoid of arrogance who subordinates himself to the teacher will certainly be helped.

Nine at the top means: In punishing folly, it does not further one to commit transgressions. The only thing that furthers is to prevent transgressions. Sometimes an incorrigible fool must be punished. He who will not heed will be made to feel. The punishment is quite different from a preliminary shaking up. But the penalty should not be imposed in anger; it must be restricted to an objective guarding against unjustified excesses. Punishment is never an end in itself, but serves to restore order.”

(My commentary: The I Ching is a teacher and advises both students and teachers on how to be in a healthy relationship.)

Carl Jung received hexagram 50,  Ting, the Cauldron with nines in the second and third place, in response to his question about presenting the I Ching to the West. The Cauldron represents nourishment. The trigram Li “Fire” sitting above the trigram Sun, “wood/wind”. “Nine in the second place means: There is food in the Ting, my comrades are envious, but they cannot harm me. Good Fortune.” Nine in the third place means: “The handle of the Ting is altered. One is impeded in his way of life. The fat of the pheasant is not eaten. Once rain falls, remorse is spent. Good fortune comes in the end.”

Ting, the Cauldron with nines in the second and third place, in response to his question about presenting the I Ching to the West. The Cauldron represents nourishment. The trigram Li “Fire” sitting above the trigram Sun, “wood/wind”. “Nine in the second place means: There is food in the Ting, my comrades are envious, but they cannot harm me. Good Fortune.” Nine in the third place means: “The handle of the Ting is altered. One is impeded in his way of life. The fat of the pheasant is not eaten. Once rain falls, remorse is spent. Good fortune comes in the end.”

Jung goes on to say that the I Ching was observing that although the spiritual nourishment is available (food in the Ting), it was being neglected (the fat of the pheasant, the most valuable part, is not eaten). But perhaps the new audience will appreciate what it has to offer. (Good fortune comes in the end.)

Here’s hoping good fortune comes to all. Wisdom is everywhere, but there are places where the essence of wisdom is highly concentrated. For those of us immersing ourselves in the natural world, this several thousand year old masterpiece is one such place. May it offer you insight and guidance on your journey through life. Remember ‘youthful folly’ can be the beginning of learning.