An embodied yoga practice allows the possibility of decoding the Sanskrit lessons imparted in the Yoga Sutras without too many trips to the  dictionary, because yoga is ultimately experiential and not a collection of ideas.

dictionary, because yoga is ultimately experiential and not a collection of ideas.

There are two great discoveries offered by Patanjali. First, we are always in direct connection with the infinite Ground of Being, known in the Yoga Sutras as Purusha, or drashtuh, the Seer. In Vedanta, this discovery is known as atma-jnanam, knowledge of the true nature of the Self. However, as humans, we tend to forget this reality, stop feeling whole and at peace, and become spiritually confused.

Therefore, Patanjali’s second great revelation is that there are many psychological, emotional and spiritual practices or disciplines available to us to help dissolve this confusion and help us return to feeling whole. These skillful means or upayas are cultivated by tapping into the wisdom of life itself, awakening the innate intelligence, aka buddhi, and discovering that embodiment of the Divine, whether as a galaxy, a star, or a human being, always involves a balance of complementary forces and energies, known as yin and yang, or the dvandvas. (II-48, tato dvandva anabhigatah)

Patanjali does not spend many sutras on atma-jnanam. He mentions it at the beginning in I-3, as drashtuh svarupe avasthanam, returns to it in the very last sutra, IV-34, and that’s about it. (The Upanishads and the Bhagavad Gita offer very rich and metaphorical descriptions of embodying Self Knowledge, so perhaps Patanjali did not feel the need to replicate those.) But he does an amazing job of offering maps and models of the mind states that create problems, and practices to heal the ones that are dysfunctional. Our on the mat practice will be samyama in asana.

Patanjali does not spend many sutras on atma-jnanam. He mentions it at the beginning in I-3, as drashtuh svarupe avasthanam, returns to it in the very last sutra, IV-34, and that’s about it. (The Upanishads and the Bhagavad Gita offer very rich and metaphorical descriptions of embodying Self Knowledge, so perhaps Patanjali did not feel the need to replicate those.) But he does an amazing job of offering maps and models of the mind states that create problems, and practices to heal the ones that are dysfunctional. Our on the mat practice will be samyama in asana.

The most important sutras come right at the beginning, I-2 through 1-4. We will change the order slightly, (as this is how we actually experience them), and then expand upon them a bit to give us a basic overview before we get into practice. (Please refer to the Yoga Sutras Study Section for the more literal translation and additional commentary to these and other sutras.)

I-4 vrtti sarupya itaratra: Being human is not easy. Our thinking mind complicates the world unnecessarily and this leads to what the Buddha referred to as the state of suffering, or dukkha, where we forget our own infinite spiritual nature. Identification of the self with dysfunctional beliefs and thoughts is the source of this suffering, or to use Patanjali’s terminology, of not being “in Yoga”. This creates a self sense that is inadequate, constantly needing to either add or subtract something in order to find inner peace. This is of course an impossible pursuit and shows up in the body/mind as tension, fear, anxiety, stress and trauma.

I-2 citta vrtti nirodha: This dysfunctional mind activity can be transformed by resolving the energies of these activities back into the flow of aliveness. This harmonious, elegant movement rooted in the eternal is known as the Tao in Chinese and is described in the Tao Te Ching, the famous treatise attributed to Lao Tzu. Patanjali offers many skills and practices that can be called upon to alleviate the distress and shift the self identity and we will focus on one today, samyama, described in Patanjali’s third chapter, the Vibhuti Pada. We are becoming more and more clear about the neuro-science and biology of fear, anxiety and trauma, the roots of suffering, including how they arise and how they can be healed, and we will use this to inform our practice.

I-2 citta vrtti nirodha: This dysfunctional mind activity can be transformed by resolving the energies of these activities back into the flow of aliveness. This harmonious, elegant movement rooted in the eternal is known as the Tao in Chinese and is described in the Tao Te Ching, the famous treatise attributed to Lao Tzu. Patanjali offers many skills and practices that can be called upon to alleviate the distress and shift the self identity and we will focus on one today, samyama, described in Patanjali’s third chapter, the Vibhuti Pada. We are becoming more and more clear about the neuro-science and biology of fear, anxiety and trauma, the roots of suffering, including how they arise and how they can be healed, and we will use this to inform our practice.

I-3 tada drashtuh svarupe avasthanam: When the dysfunctional activity ceases, the Infinite Ground of Being shines forth, the “I AM”, the sense of self, dissolves into this, and remains stable there . There is an ‘Awakening’ to the fact that ‘I am wholeness’ that is both unimaginable and indisputable. In the Zen tradition, this glimpse into one’s true nature is called Kensho or Satori. The Japanese character for satori is depicted on the left.

I-3 tada drashtuh svarupe avasthanam: When the dysfunctional activity ceases, the Infinite Ground of Being shines forth, the “I AM”, the sense of self, dissolves into this, and remains stable there . There is an ‘Awakening’ to the fact that ‘I am wholeness’ that is both unimaginable and indisputable. In the Zen tradition, this glimpse into one’s true nature is called Kensho or Satori. The Japanese character for satori is depicted on the left.

However, the identification process, a specific type of mind activity, (ahamkara) often eventually reverts back to its habit of feeling separate and lacking. Thus the ‘Awakening’ is often unstable in the beginning. It may last minutes, hours, or even days, but can’t quite stick. Thus Patanjali requires the stabilizing of the awakening to be considered “being in Yoga” by using the term ‘avasthanam’. In sutra IV-27 and IV -28, Patanjali returns to the process of stabilizing the awakening.

The spiritual irony of this is that we are always connected to The Ground of Being, because that is all there is, there is only wholeness. We forget, get distracted, and before we know it, are totally lost in delusion (avidya). This is the story of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, the “Fall from Grace” as depicted here on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

The spiritual irony of this is that we are always connected to The Ground of Being, because that is all there is, there is only wholeness. We forget, get distracted, and before we know it, are totally lost in delusion (avidya). This is the story of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, the “Fall from Grace” as depicted here on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

Our practice on the mat is to re-solve the dysfunctional mental patterns that manifest as thoughts and beliefs that have an immediate affect on the cells, tissues and organs. If we carry the water image further, we are dissolving, like salt into water, these patterns  of mind activity (citta vrttis) into the feeling of Oneness. It is tangible, visceral opening that emerges when the organism feels totally safe and very awake. Usually our being awake carries fear or anxiety of danger, as this is the biological priming of our nervous systems. Danger lurks, and you will survive if you are on alert. And feeling safe by itself usually doesn’t take us into the spiritual breakthrough. There has to be an openness, alertness, curiosity and intention to stay present to whatever is arising known as mindfulness. Mindfulness, a mind state that gets stronger through practice, will allow us to sustain our practice through the moments when we do not feel totally safe and will allow the samyama in the postures to also strengthen.

of mind activity (citta vrttis) into the feeling of Oneness. It is tangible, visceral opening that emerges when the organism feels totally safe and very awake. Usually our being awake carries fear or anxiety of danger, as this is the biological priming of our nervous systems. Danger lurks, and you will survive if you are on alert. And feeling safe by itself usually doesn’t take us into the spiritual breakthrough. There has to be an openness, alertness, curiosity and intention to stay present to whatever is arising known as mindfulness. Mindfulness, a mind state that gets stronger through practice, will allow us to sustain our practice through the moments when we do not feel totally safe and will allow the samyama in the postures to also strengthen.

Our first exploration on the mat will be finding the balance of weight and lightness.

(Follow the link!) From the perspective of the organism, the first question of safety is ‘where am I’. The first orientation, where to bring attention (dharana), is to the felt sense of weight. Find the felt sense of weight. Stay there. Live there. Patanjali calls this embodied state of being grounded ‘sthira‘ and is deepening our connection to Mother Earth, at all levels of reality.

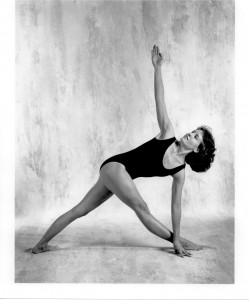

The second orientation is to the space around me. I need to feel safe in my environment. I find this in movement, and through the felt sense of lightness or levity which allows me to float in grounded-ness, like a fish in water. I become 3 dimensional in perception and action. Patanjali calls this ‘sukha‘. Thus, to be fully embodied is to be both sthira and sukham, as Patanjali describes in II-46. Staying in this dynamic state of balance, of weight and lightness, roots and wings, with action, perception and intelligence flowing as an single stream, begins the samyama.

Take this awareness into the standing poses (follow the link), and we will add one more clue from Patanjali to integrate into the samyama. The first two practices Patanjali introduces, even before samadhi, are abhyassa and vairagya. On the mat these are related to how we use energy in the poses. Abhyassa is the disciplined and conscious direction of your energy towards healing. In asana, it means to deepen the stability of the samyama by bringing more cells, organs and tissues into the conscious flow. It is a choice to bring your attention to a highly refined state. Vairagyam is the complementary practice. It involves withdrawing of energies away from patterns that are hyper-tonic (excess rajas) or hypo-tonic (excess tamas). Where in my body/mind am I overworking? Too aggressive? Overly contracted? Where in my body/mind am I dull, unconscious, asleep? Take from here, add to there, all the while monitoring action and perception to feel how the changes are actually manifesting.

the mat these are related to how we use energy in the poses. Abhyassa is the disciplined and conscious direction of your energy towards healing. In asana, it means to deepen the stability of the samyama by bringing more cells, organs and tissues into the conscious flow. It is a choice to bring your attention to a highly refined state. Vairagyam is the complementary practice. It involves withdrawing of energies away from patterns that are hyper-tonic (excess rajas) or hypo-tonic (excess tamas). Where in my body/mind am I overworking? Too aggressive? Overly contracted? Where in my body/mind am I dull, unconscious, asleep? Take from here, add to there, all the while monitoring action and perception to feel how the changes are actually manifesting.

And all the while feeling the ever-present Divinity radiating with more and more brightness from your heart out into the world.