Lesson 2

Mindfulness / Mindful Awareness What is Mindfulness?

What is mindful awareness and why is this the very first theme introduced in this course? Along with concentration and insight, mindfulness is one of the three aspects of meditation articulated by the Buddha 2500 years ago and refers to the capacity to be fully present to what is arising, on as many levels as possible, right here, right now, in this moment. It is  the primary practice in the Vipassana lineage of Buddhism and is beautifully articulated in the writings of contemporary American teachers Sylvia Boorstein, Joseph Goldstein, Jack Kornfeld, Larry Rosenberg, Sharon Salzberg and John Kabatt-Zinn.

the primary practice in the Vipassana lineage of Buddhism and is beautifully articulated in the writings of contemporary American teachers Sylvia Boorstein, Joseph Goldstein, Jack Kornfeld, Larry Rosenberg, Sharon Salzberg and John Kabatt-Zinn.

In the Anapanasati Sutra (mindfulness on the flow of inbreath and outbreath) Buddha teaches mindfulness as 16 very specific practices exploring what he calls the ‘Four Foundations of Mindfulness. These are: awareness of the bodily sensations, awareness of our feelings and emotions, awareness of our thoughts, and awareness of the ultimate impermanence of anything that arises in the moment. We will return to these explorations later, but first we will look more deeply at just what we mean by mindfulness.

Sustaining a mindful state, that is, being fully present, moment to moment, over time, is not necessarily easy because it requires the developing and stabilizing of a meta-level of awareness, an outside of time observing or witnessing state that is quite different from the time bound mental activities of thought, memory and perception that tend to dominate the mind of the average human. However, and this is the hidden gem of the practice, the mindfulness state is always available, again and again, in every moment, as it is the moment. It is the ‘Now’ of Eckhart Tolle’s popular book, “The Power of Now”.

What is the opposite of mindfulness? I guess we could call it mindlessness, but it is a mind that has forgotten the present moment because it has become lost in the past and/or future, which only exist in the realm of thought. From this point of view, mindfulness must be something that will arrive in the future. Scientist and spiritual practitioner Jon Kabatt-Zinn captures this paradox, and the power and urgency of awakening mindfulness in the beginning of his book “Coming to Our Senses”.

“I am not speaking of some distant future in which, after years of striving, you would finally  attain something, taste the timeless beauty of meditative awareness and all it offers, and ultimately lead a more effective, and satisfying and peaceful life. I am speaking of accessing the timeless in this very moment–because it is always right under our noses, so to speak—and in doing so, to gain access to those dimensions of possibility that are presently hidden from us because we refuse to be present, because we are seduced, entrained, mesmerized, or frightened into the future and the past, carried along in the stream of events and the weather patterns of our own reactions and numbness, attending to, if not obsessing about what we unthinkingly dub ‘urgent’, while losing touch at the same time with what is actually important, supremely important, in fact vital for our own well-being, for our sanity, and for our very survival. We have made absorption in the future and in the past such an overriding habit that, much of the time, we have no awareness of the present moment at all. As a consequence, we may feel we have very little, if any, control over the ups and downs of our own lives.”

attain something, taste the timeless beauty of meditative awareness and all it offers, and ultimately lead a more effective, and satisfying and peaceful life. I am speaking of accessing the timeless in this very moment–because it is always right under our noses, so to speak—and in doing so, to gain access to those dimensions of possibility that are presently hidden from us because we refuse to be present, because we are seduced, entrained, mesmerized, or frightened into the future and the past, carried along in the stream of events and the weather patterns of our own reactions and numbness, attending to, if not obsessing about what we unthinkingly dub ‘urgent’, while losing touch at the same time with what is actually important, supremely important, in fact vital for our own well-being, for our sanity, and for our very survival. We have made absorption in the future and in the past such an overriding habit that, much of the time, we have no awareness of the present moment at all. As a consequence, we may feel we have very little, if any, control over the ups and downs of our own lives.”

This feeling of being out of control as Jon describes is known as suffering (dukha) in Buddhism and is a universal human experience. Mindfulness offer us a radically different point of view that is the path away from suffering and into a way of being that is inherently sane, creative and balanced. Many students come to yoga because of a desire to change something. Maybe they want a more flexible and strong body than the one they have now. Maybe they want to relieve their back pain, or want to learn how to relax. Or maybe they want to improve their self-esteem by becoming spiritual or getting better and better at doing the yoga poses and sequences. The hidden suffering behind all of these seemingly reasonable desires must be seen as quickly as possible.

How Mindfulness Relates to Classical Yoga

Patanjali, as an articulate exponent of yoga, understood the nature of suffering, although he used a slightly different language than the Buddhists. What the Buddhists refer to as the ‘end of suffering’ and others call enlightenment, self-realization, being ‘one with God’, ultimate freedom and so on, Patanjali calls yoga. His definitive treatise, The Yoga Sutras, begins with a clear description of how we are either free from suffering, that is, in the state of yoga, or not.

I-2 yogash citta vrtti nirodhah:

Yoga is the resolution of the (dysfunctional/dissociated) mind states.

I-3 tada drashtuh svarupe avasthanam:

Then the identity of the Self with pure Awareness becomes stable.

I-4 vrtti sarupyam itaratra:

(At other times, i.e., in dysfunctional mind states) mind activity is mistaken for the Self.

I-5 vrttaya panchatayaha klishtaa klishtaaha

Mind states can be functional or dysfunctional and come in 5 general categories

With some reading between the lines (always necessary in studying sutras), we can discover that freedom involves coming to an understanding of how the mind functions and how we come to know about the reality of world and of ourselves. In other words, can we become ‘mindful’ of the functioning of our own inner world. Several key points stand out in these sutras.

1. There is a self-sense, a sense of “I” that wants to know itself.

In the Bhagavad Gita, Arjuna is ‘everyman’, the student of yoga and spiritual seeker that yearns to know ‘who am I?” Krishna, the incarnation of Divine wisdom and Compassion, uses 18 chapters to instruct him. We need to be mindful of our own self sense, in all of its layers.

2. This self sense tends to be unstable, oscillating between feeling ‘safe’ and feeling ‘not-safe’.

Our own personal experience of the present moment seems to consist of two aspects of reality: myself (my self-sense, the one who sees, ) and everything else (the seen, the ‘not-self’). Once we start to become ‘mindful’ of our own inner world, that is, we observe the ongoing flow of the mind, we begin to notice that what we call self and what we call not self are often changing and our sense of safety is definitely related to these changes.

Sometimes our self sense is unhealthy and leads to self criticism, self judgement and diminished self esteem. We feel unsafe and threatened from the glare of our own inner gaze. At other times our self sense is relaxed and confident and we experience life joyfully.

Similarly, sometimes our sense of other is unhealthy and we experience something in the present moment as an enemy, as threatening and dangerous, though a rational observation would find no threat. And, at other times, we can sense the world around us with appreciation, delight and awe, or at least compassionate understanding.

As we become more experienced in the capacity to observe the flow of phenomena in the mind, we begin to recognize the relationship between mind activity, the ideas, thoughts beliefs arising in the moment, the mind states that underlie them, and our overall sense of being safe or under threat.

Mind states include not just the thoughts but all of the neuro-physiological activities activities arising in the moment, including blood pressure, respiratory rate, cardiac output, muscle tone, digestive activity and more. These states have roots in the primal structures of the brain that are constantly assessing issues of safety and security. Here the emotional energies mobilize our physiology to fight, flee or freeze if we feel threatened, or to relax, open and curiously approach the moment if we feel safe.

These are total body experiences and are the sub-stratra of the mind-states that give rise to mind activity. I love Dan Siegel’s work because he identifies and emphasizes the embodied nature of mind and relationships, and here is where our hatha yoga enquiry truly meets mindfulness practice as articulated by the Buddha as we see the bodily sensations are connected to our emotions, which give rise to thoughts, and all of these are transient phenomena arising and disappearing in the infinite spaciousness of Buddha Nature/drasthuh svarupe.

3. The self sense recognizing ‘the unbounded spaciousness of Awareness is Self’ is yoga.

This possibilty arrises with establishing a deep seated sense of security and safety in the mind field. The ever present, infinitely spacious openness is always available. Feeling emotional safety, “I am safe”, leads to the possibility of deep openness to the present. I can ‘let go’ of any need to hold on for safety. I trust, I feel, I know that I am safe. I surrender to the mystery of existence.

4. The self sense identifying with mind activity (I am my thinking) is not yoga but is dysfunctional mind activity, or suffering.

The mind indentifying with fear and anxiety, a mind/body ‘holding on’ to anything it can find, suffers. The suffering can be mild moderate or intense.

5. Mind activity is not the problem. Identifying (confusing) mind activity as the Self is the problem.

When I am safe, my mind is free to blossom, to create, to participate in healing. No need to hold on when I am in the flow of life. No need to inhibit my thoughts. But I do need to weed out the roots of suffering.

6. Not all mind activity is dysfunctional.

7. It is possible to eliminate dysfunctional mind activity.

Mindfulness is an enquiry into the world of awareness, mind/body activity and the self sense. When we are present to what is arising in this moment, we are allowing our attention to take in the outside world, through our senses and sensitivity, and also our own inner world of thoughts, feelings and bodily sensations. These all co-arise simultaneously.

What are the keys aspects to mindfulness practice?

Although mindfulness is most often associated with Buddhism, it is essentially a human practice and if we look more deeply, we see that truly staying in the present moment, over time, is not at all an easy thing to so in the beginning. Much of what arises can be unpleasant, uncomfortable, or downright terrifying and the mind will find any excuse to escape. But with discipline and patience, mindfulness is something that can be cultivated and nurtured by anyone at any time throughout their lives, and can eventually become your permanent state.

Dan Siegel. a pediatric psychiatrist and author of “The Developing Mind” and ‘The Mindful  Brain”, has worked with Jon Kabatt Zinn in mindfulness meditation and is bringing his neurobiological understanding to help promote and explain this ancient practice. He describes four key features of mindfulness that we can use to remain present under difficult circumstances and these will be the foundational practices employed throughout the course. Dan is an anacronym guy, so his mnemonic for mindfulness practice is COAL.

Brain”, has worked with Jon Kabatt Zinn in mindfulness meditation and is bringing his neurobiological understanding to help promote and explain this ancient practice. He describes four key features of mindfulness that we can use to remain present under difficult circumstances and these will be the foundational practices employed throughout the course. Dan is an anacronym guy, so his mnemonic for mindfulness practice is COAL.

Curiosity, Openness. Acceptance, Love.

Curiosity: What is this? Why is this so? Like a young child, the mindstate of mindfulness begins with curiosity. Now this is important because it is possible to be very alert and focused in the present out of fear. The sense of danger can be very helpful in remaining in the present, but the underlying emotions and physiology of this approach can be extremely damaging to ones physical and emotional health. My experiences with two of my main teachers offer stark contrasts in style when it comes to creating a field of attention in the present.

My first experience of studying with B.K. S. Iyengar in Pune India back in early 1982 was a strong lesson in focus by fear. Even before the first class began, as we were milling about on the ground floor waiting to go up to the yoga studio, you could feel and smell the fear of the students. When we finally were allowed into the yoga studio and took our places with Iyengar strolled around sizing us up, we were all focused. He could feel if we were not paying attention from far across the room, and we knew this, and he was not afraid to remind us. He has earned the nickname ‘the lion of Pune”.

Fortunately for all of us, Iyengars ‘moods could just as easily swing in the opposite way. He would relax, lighten up, teach from a radically different place, and I had a very different internal experience. My curiosity would emerge more fully and a whole new level of learning opened up for me. But, as I was to experience again and again, especially in those earlier days, at any moment he could shift back to the fear mode and my own internal contractions returned. It was a great lesson to me that has taken many years to fully appreciate.

Swami Dayananda has as different approach to holding the attention of his students. If he feels that he is losing them, he stops teaching and starts telling jokes. He doesn’t have a staff of writers to keep him up to date, so after a while, you have heard most of his repertoire, but his delivery is impeccable. He knows how to get you to relax, to laugh, to forget about your worries and problems and just let go into the infinite spaciousness of laughing. Then, he will resume his teaching. A worried or unfocused mind cannot hear the teaching. It will not penetrate.

Swami Dayananda has as different approach to holding the attention of his students. If he feels that he is losing them, he stops teaching and starts telling jokes. He doesn’t have a staff of writers to keep him up to date, so after a while, you have heard most of his repertoire, but his delivery is impeccable. He knows how to get you to relax, to laugh, to forget about your worries and problems and just let go into the infinite spaciousness of laughing. Then, he will resume his teaching. A worried or unfocused mind cannot hear the teaching. It will not penetrate.

It is important to be focused and relaxed. This is the attentional state of curiosity. The organism feels safe and secure and the whole nervous system reflects this. We need to nurture this state, not the fear state.

Openness: Well, what if we are afraid, if we do feel fear? Can we be open to that reality, and have some curiosity about the fear? It is easy to be curious about things that feel good, that are pleasant. Things that are unpleasant, I don’t think so. The second aspect of mindfulness is the quality of being open to whatever arises, and this usually refers to those thoughts, feeling, or emotions that I want to reject or repress because they are too painful to look at, to re-experience. It is important to be able to separate fear based on real life situations (an automobile coming at me as I cross a street) from our own confusion coming from the past and learn to work with each differently.

Acceptance: Acceptance is even more difficult than openness. Can I not only be open to whatever the present moment brings, but can I also fully accept what is arising. Can I own my own faults, weaknesses and mistakes without being afraid of them. Acceptance begins to arise as I start to realize more and more that “I” am awareness that is noticing, not ‘what’ I am noticing.

Love: To complete our mindfulness state we add the most difficult part. OK, I accept that I have screwed up, that I have aspects that are painful, that the world is not perfect. Now, can I truly, unconditonally love these unpleasant if not repulsive aspects of reality, of my mind, of the world. Again, what begins to change over time is the identity factor. More and more I identify with the timeless presence, which is love, and ‘loving what is’ is the most natural thing in the world. Byron Katie’s book, “Loving What Is” is her own personal story of this level of awakening and is quite moving.

In the Anapanasati Sutra (mindfulness on the flow of inbreath and outbreath) Buddha teaches how the breath is the vehicle to explore the ‘Four Foundations of Mindfulness’ : awareness of the bodily sensations, awareness of our feelings and emotions, awareness of our thoughts, and awarenes of the ultimate impermanence of anything that arises in the moment. (In “Breath By Breath” Larry Rosenberg takes us step by step through the Anapanasati Sutra’s 16 practices, 4 for each of the four foundations.)

We will begin with the first foundation, using the breath to bring awareness, as well as curiosity, openness, acceptance and love, to the sensations of the body, and especially the breath, as we sit.

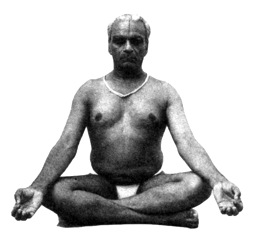

First Posture: Sitting: sukhasana, or the easy pose. This can also be done in a chair. Most students should sit on a bolster or folded blanket so that the knees can drop below the hips and the spine feels spontaneously light.  Adjust sitting bones by rolling back and forth until you find a place of balance. Imagine a line of energy extending through your core, from the heavens down through your crown and on into the earth. Feel the earth energy rising up through your core, through your crown into the sky. Find the balance of ascending and descending energies and rest there. Then, notice the breathing and following its movements through the body. Where do you feel movement, where do you feel heavy, where do you feel stuck, where do you feel free? We are just taking notes, no need to correct the posture. Just observing, being mindful of what sensations and feelings arise moment to moment. And noticing that the mind may drift off in other directions as well. Gently bring your attention back to the breath, the sensations the feelings.

Adjust sitting bones by rolling back and forth until you find a place of balance. Imagine a line of energy extending through your core, from the heavens down through your crown and on into the earth. Feel the earth energy rising up through your core, through your crown into the sky. Find the balance of ascending and descending energies and rest there. Then, notice the breathing and following its movements through the body. Where do you feel movement, where do you feel heavy, where do you feel stuck, where do you feel free? We are just taking notes, no need to correct the posture. Just observing, being mindful of what sensations and feelings arise moment to moment. And noticing that the mind may drift off in other directions as well. Gently bring your attention back to the breath, the sensations the feelings.

If the back muscles get tired, use a chair, or lie down. Just try not to fall asleep. Just notice all the thoughts, sensations, emotions and movements that come and go. Some may seem to stay, but even they will change, mutate, dissolve eventually. When you can do this for 10 minutes at a time, try 15. But try not to get discouraged if it seems impossible. We often are resisting unconsciously, but with patience and persistence some settling in will happen.

The next level is to bring this sensitivity to all of your daily activity. Remember, this is not about being ‘self conscious’. The point is not to try to watch ‘yourself’. That would drive a saint crazy. Just notice the moment, at as many levels as reveal themselves. You will be surprised at how much is there, waiting to be noticed.