Who could ask for anything more?

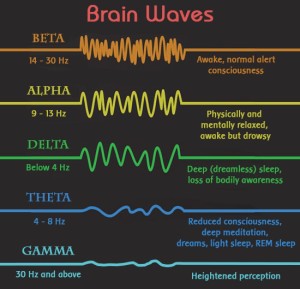

One of the major means of facilitating shamanic journeying is the rhythmic beating of a drum or shaking of a rattle, to help the brainwave patterns shift to 4 – 8 cycles per second (Hz) theta waves, the range just above the delta waves of dreamless sleep, but just below the alpha waves of waking consciousness. This dream state band is a rich source of information about not only our inner world, but also about the hidden dimensions of the outer world. What is it about rhythm that is so powerfully transformative? There is no culture on the planet that does not have a rich tradition in music and dance, including India, home of yoga, so we may discover the roots of yoga embedded in the inner rhythms of our embodied being. What is the connection between rhythm and our aliveness?

Many eons ago Mother Nature decided a nervous system would be useful for life on planet earth. Animals (as opposed to plants, which do not have nervous systems) needed to be able to move about their environment, to find food, mates and shelter, while simultaneously avoiding danger. The nervous system evolved to coordinate perception, prediction and movement so animals could learn and master certain survival skills that could be called upon in a moments notice. Mother Nature’s secret to coordinating this complex system is rhythm.

Rodolfo Llinas, In ‘I of the Vortex: From Neurons to Self’ develops a model of how timing waves generated in localized neuronal structures modulate global neuronal activity, much as a conductor sets the pace and dynamics for an orchestra. He describes the origins of the nervous system, and the related mind and ‘the mindness state’ as the need for “predictive interactions between mobile creatures and their environment.” (Here is the beginning of dance.) “Neurons arose within the space between sensing and moving. This space mushroomed to become the brain.” (The possibilities of dance became more and more complex.) “Neurons came into existence in order to facilitate and orchestrate the ever-growing complexity of sensori-motor transformations.” (Action and perception are integrated rhythmically. As we yogis know that samyama is the integration of the organs of action and the organs of perception with the intelligence to create a single conscious movement within the entire body, we can now say that yoga involves learning how to shake your buddhi. )

Rodolfo Llinas, In ‘I of the Vortex: From Neurons to Self’ develops a model of how timing waves generated in localized neuronal structures modulate global neuronal activity, much as a conductor sets the pace and dynamics for an orchestra. He describes the origins of the nervous system, and the related mind and ‘the mindness state’ as the need for “predictive interactions between mobile creatures and their environment.” (Here is the beginning of dance.) “Neurons arose within the space between sensing and moving. This space mushroomed to become the brain.” (The possibilities of dance became more and more complex.) “Neurons came into existence in order to facilitate and orchestrate the ever-growing complexity of sensori-motor transformations.” (Action and perception are integrated rhythmically. As we yogis know that samyama is the integration of the organs of action and the organs of perception with the intelligence to create a single conscious movement within the entire body, we can now say that yoga involves learning how to shake your buddhi. )

From the back cover of ‘I of the Vortex’: “At the heart of Llinas’ theory is the concept of oscillation. Many neurons possess electrical activity, manifested as oscillating variations in the minute voltages across the cell membrane. On the crests of these oscillations occur larger electrical events that are the basis for neuron to neuron communication. Like cicadas chirping in unison, a group of neurons oscillating in phase can resonate with a distant group of neurons. This simultaneity of neuronal activity is the neuro-biological root of cognition. Although the internal state that we call the mind is guided by the senses, it is also generated by the oscillations within the brain. Thus, in a certain sense, one could say that reality is not all “out there”, but that we live in a kind of virtual reality.”

Not that we need to ground our shamanic experiences in science, but here we are. We are resonant with the world around us at a multiplicity of frequencies, both internal and external, and we build a sense of reality and self from our perceptions of these fluctuating rhythms. How many of these resonances do we actually perceive, how many are fully activated and integrated into our daily activities, how many others are available to explore in our practice?

Llinas goes on to propose that in the background of the brain, “continuously humming”,  are 40 Hz coherent electrical waves linking the thalamus and cerebral cortex in timing waves that may be the basis for a ‘self sense’. As we mentioned above, the shamanic journeys often involved traveling on the 4 – 8 Hz theta wave frequencies in the brain. There are many other rhythms of aliveness available for exploration as well.

are 40 Hz coherent electrical waves linking the thalamus and cerebral cortex in timing waves that may be the basis for a ‘self sense’. As we mentioned above, the shamanic journeys often involved traveling on the 4 – 8 Hz theta wave frequencies in the brain. There are many other rhythms of aliveness available for exploration as well.

Practitioners of Chinese and Tibetan medicine learn to read the pulsing of the heart and circulatory system and a skilled practitioner can differentiate 24 – 29 different types of pulse. Heart beats run in the 40 – 100 beats per minute, translating to .8 – 1.6 cycles per second. Craniosacral therapists tune into the three tidal rhythms of the cerebro-spinal fluid system. These much slower rhythms include: the cranial rhythmic impulse at 8 – 12 cycles per minute; the middle tide at 2 – 2.5 cycles per minute, and the very subtle long tide is 90 – 100 seconds per cycle. We will explore these craniosacral rhythms in a future post.

Yogis and other somanauts learn to travel on the physiological frequencies of the respiratory system, and our exploration in the next few posts will be to play with these in pranayama practice. The breath is universally acknowledged as a gateway into the inner functioning of mind and body as it links the structures, diaphragm, ribs, spine and limbs with all of the emotions, from fear and anxiety, to delight and joy. We will learn how to ride the rhythmic oscillations of the breath like a surfer and possibly discover new worlds and new rhythms of connectivity between our selves and the inner realms of creation.

The first step, and our practice today, is to establish contact with the feel of the breath and dive deeply into its waters. In yogic terms, it is dharana – dhyana – samadhi aka samyama applied to the flow of energy we call breathing. The fundamental rhythmic pattern has four stages: inhalation where the lungs fill; exhalation where they empty; a brief pause where the inhalation ends and before the exhalation begins; and another pause after exhalation and before the inhalation begins. In a normal healthy breath, these pauses are smooth and fluid. There is no residual tension. If very relaxed, the pause after exhalation may be quite long, revealing a deep inner stillness. (Remember that all energetic processes arise in stillness and look to find completion by returning to stillness.) These pauses are unique and very important in our practice.

Either lying or sitting in a comfortable position, let your attention move to and stay with the breath. (This is meditation 101.) Sustain the sense of being suspended in the breath while your curiosity awakens. Some questions to consider: How does the skin move/respond to the breathing? the bones? the large outer muscles? the smaller, inner muscles?, the pelvic organs? the abdominal organs? the heart and lungs? the neck, throat and face? And: can you feel your diaphragm? your intercostal muscles? Many questions for many days and years of practice. Perhaps only one is needed to nourish you in this practice session.

Allow the breath to become smoother and softer by dropping whatever tension and sense of effort you can. Pay special attention to the pauses. The breath may become more shallow, or possibly deeper. Either way, let the breath lead you. You are feeling, listening, receiving sensation riding on the waves of breath. Let the breath lead you deep into the stillness and rest there. Let the stillness radiate out through your cells. Nurture this state so it becomes easier and easier to access. Then bring it into your daily activities.

Here is Patanjali on pranayama, (with my commentary) from the Sadhana Pada.

Here is Patanjali on pranayama, (with my commentary) from the Sadhana Pada.

II- 49 tasmin sati shvaasa-prashvaasayor gati-vicchedah praanaayaamah

The mastery of asana allows the exploration of more subtle life energies through regulating the natural flow of inhalation and exhalation.

Mastery of any asana means the ability to sustain the posture through time without any aggression or dullness in the organism. This is the natural state of the animal kingdom but because the human mind can interfere with this natural state of relaxed aliveness we need the interventions learned in asana. Eventually asana, the innate intelligence of posture and movement sustains itself as we move through life. (We do need to keep practicing to maintain this!) When the outer layers of the body, the musculo-skeletal system, are harmoniously integrated (sattva) the more subtle physiological or organic movements are seen more clearly and they may reveal more subtle blockages in the pranic flow. Pranayama practice is a way to help dissolve these blockages.

II- 50 baahyaabhyantara-stambha-vrttih desha-kaala-sankhyaabhih paridrsto diirgha-suukshmah

The movements of breath are outward, inward and restrained. Practice involves allowing the stages of the breath to become longer and more subtle as you explore where the breath is felt inside the body, how longs the movements take, and how many cycles you can perform safely.

Pranayama is not a practice of the will the way asana can be. It emerges as a natural sensitivity to the pranic flow that you can ride the way a hawk rides a thermal or a school of fish rides ocean currents. The practice involves constantly getting out of the way of aliveness, of dissolving the subtle blockages in the pranic flow from emotional memories and habits, and releasing the inner currents of prana through the organs and cells.

Although Patanjali mentions three movements of the breath, there are technically four: exhalation (rechaka), restraint or retention after exhalation (baahya kumbhaka), inhalation (puraka), and retention after inhalation (antara kumbhaka). The two retentions are different from each other because of the physiology of respiration and are included in the more advanced forms of pranayama

Inhalation is a neurologically initiated action. When the CO2 level in the blood reaches a certain level, the vagus nerve triggers the diaphragm to contract and draw air into the lungs. Exhalation does not have such a trigger and thus we often have to learn to exhale. This is especially true in cases of COPD, emphysema and asthma where sufferers struggle to inhale into lungs that have no room because the exhalations have been forgotten. In yoga, the exhalation is learned first as it is calming to the nerves and mind. Then, when exhalations comes easily, inhalation can begin to be prolonged. Trying to force air into lungs still half full is stressful and pranayama is about releasing stress, not adding more.

Over time, the ribs, diaphragm and spine become more elastic and integrated and the breathing cycles flow more and more effortlessly. Then you begin to notice the natural pauses that arise at the end of the in breath and again at the end of the out breath. These ‘restraints’ are spontaneous and natural. As your pranayama practice becomes more relaxed, you begin to prolong the pause after the in breath. This is known as retention after in breath or antara kumbhaka. As there is no reflex to exhale, this is safe. The ribs are sustained in an open state and the diaphragm is suspended dynamically. Ideally there is no sense of strain or effort but simply an allowing of the lungs to absorb more and more of the oxygen and release more of the CO2.

In baahya kumbhaka, retention after exhalation, the lungs and blood stream have become so saturated with oxygen from the expanded inhalations and retentions that there is no reflex to inhale for quite some time. This is a very quiet internal state and can lead to the experience of a new level described next.

II- 51 baahyaabhyantara-visayaaksepii caturthah

The fourth (in addition to outward, inward and restrained) surpasses the limits of outward and inward.

This suspension of the breath is spontaneous and not the result of the previous mentioned kumbhaka practices. In other words, there is no sense of ‘practicing pranayama’, but of resting in deep neurological stillness.

II- 52 tatah ksiiyate prakaashaavaranam

Then the covering of illumination is weakened.

Obscurations is a lovely Buddhist word describing the nature of the dull or stuck (tamasic) and agitated or chaotic (rajasic) mind states and activities that are said to cover the inner light of seeing, vidya, of the Seer resting in unbounded awareness. Even the breath can be seen as a very subtle disturbance and when the mind is in deep rest, the breath is effortlessly suspended and only light remains. This is not an action of the will, but the result of a natural stillness.

II- 53 dhaaranaasu ca yogyataa manasah

And the mind becomes fit for concentration

Manas is that aspect of mind dealing directly with the senses and thus it is often busy. When it is still and undisturbed, buddhi, the aspect of mind that sees, is now ready for its refinement. The vital energies, as prana, have been calmed and clarified by pranayama practice leaving an alert stillness in the mind field.

Photo of George and Ira Gershwin courtesy of Stephen Pond.