Falling Awake

Keep up your meditation practice, with the primary intention to relax into Awareness and let everything flow through you. We can call this resting in Stillness or Silence, with no attempt to inhibit the flow of thoughts, ideas and emotions. There is an inhibition of our reactivity to the stream by shifting in attention from the constantly changing world on the surface of the mind to the inner depths. Then, like falling asleep, we let go, falling awake, dissolving into awareness. Awareness resting in and as itself.

This is not easy to do, or should I say ‘not do’. But if we can open-heartedly accept the reality of your mental states, every once in awhile, we will forget the efforting and, voila, the magic of presence is there, resting as the ultimate stability of the unchanging Ground of Being. This is the ‘Ishvara Pranidhana’ of the Yoga Sutras, (PYS I-23), letting go into Divinity in its fullest sense. We need to practice, abhyasa, with open hearted devotion, continuously, for a long period of time, like forever, to be truly anchored here. (See PYS I-13 and I-14). This is the nivrtti marga mentioned in the previous post.

Now, back to our engagement with the wonderful world of form, or what Patanjali refers to as Prakriti, as we traverse the pravrtti marga in our somatic practice. The on-going goal of our practice is to continue to open our human energy field to become more balanced, integrated and coherent, within our unique selves and the Cosmos as a whole. This allows the Ground of Being to shine more clearly through the world of form, which makes it easier for the meditation practice to get stronger, deeper and more grounded, which allows the energy fields to become more coherent, which strengthens the human collective energy field, in an evolving spiral of deeper integration on the personal level and expansion of the collective intelligence. This is the evolutionary leap of our historical moment. This interplay of the inner and outer journey, our personal and relational lives, and as we will see, heart and hara, is the natural unfolding of a spiritual life.

Awakening the Lesser Peritoneal Sac

To continue to deepen our embodied integration and coherence, we will return to our Daoist models of the human energy field. (This section is long and detailed, and we will continue this theme, in differing ways, over the next few blogs, but this is the core of what you need to know.

To continue to deepen our embodied integration and coherence, we will return to our Daoist models of the human energy field. (This section is long and detailed, and we will continue this theme, in differing ways, over the next few blogs, but this is the core of what you need to know.

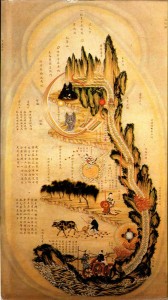

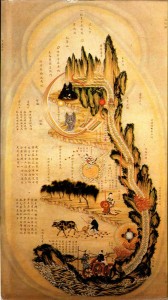

The diagram on the right shows the three dantiens, or elixir fields, as they are described in Daoist practice, along with the yin’conception vessel’ and the yang ‘governing vessel’. On a gross level, the dantiens are easy to access as they correspond to the three bony cavities; the skull, rib cage and pelvis. Physiologically, they represent organizing centers of our psycho-biological life activity, further depicted in much more metaphorical detail in  the Neijing tu.

the Neijing tu.

On yet another level they can be seen as the centers of the three means of knowing: through the abstraction of the intellect, the relational compassion of the heart and gut level intuitive instinct of the hara. The abstract intellect is the most recent in evolution, and the most problematic in modern times. It took the universe at least 4 billion years to create this mode of knowing, so we must honor it as a precious and valuable gift, but it needs to be integrated into the older wisdom of heart and hara to not be damaging to our evolutionary journey.

The organizing center of the lower dantien, known as the hara in Japanese, is the center of gravity of the human body, or the energetic center of our movements. The first and second chakras can be found in the lower dantien, and this is also the center of the lower burner as we will see in the diagram below. As a movement center, it helps coordinate the action of two legs and tail with the spine. When our attention is centered here, there is a sense of being rooted or grounded, whether while sitting in stillness, or in movement. It is the place of embodied stability, the sthira in shtira sukham asanam. Further cultivated, its opening takes us down into the mysterious depths of Mother Earth and the 4 billion years of wisdom accumulated by life on this planet.

The center of the middle dantien, the heart center, is our spiritual center, the 4th of the seven chakras, the home of Shen, the Daoist term for spirit, and is also home of the upper burner, as we will see later. It is the source of our relational intelligence and our capacity to know we are one with all of creation, manifesting as love and compassion.

The center of the middle dantien, the heart center, is our spiritual center, the 4th of the seven chakras, the home of Shen, the Daoist term for spirit, and is also home of the upper burner, as we will see later. It is the source of our relational intelligence and our capacity to know we are one with all of creation, manifesting as love and compassion.

This middle dantien is also a movement center for quadrupeds, as it helps coordinate the movements of the upper limbs and head with the spine. Quadrupedal movement involves linking the lower and middle dantiens, the dance of heart and hara. Dogs when running offer a fantastic example of this coordination in action. In the photo above, (thanks to @William_Nettmann), notice the hind legs and tail (lower dantien) extending backward as the upper legs and head (middle and upper dantiens, reach forward.

In the next photo, (courtesy of Dan Gold on Unsplash) , we see the next phase of quadrupedal running, where the energy of the limbs is gathered back to the center, like bakasana, even as head and tail continue to extend out in opposite directions for balance. To begin to embody the heart – hara dance, visualize a dog running; extend – gather – extend – gather, yang – yin – yang – yin, etc. Where do you feel this in your body. I love the fact that most of the time their feet are off the ground, like they are flying across the land. Speed and power arise form this powerful movement integration.

, we see the next phase of quadrupedal running, where the energy of the limbs is gathered back to the center, like bakasana, even as head and tail continue to extend out in opposite directions for balance. To begin to embody the heart – hara dance, visualize a dog running; extend – gather – extend – gather, yang – yin – yang – yin, etc. Where do you feel this in your body. I love the fact that most of the time their feet are off the ground, like they are flying across the land. Speed and power arise form this powerful movement integration.

How can us bipedal humans utilize this

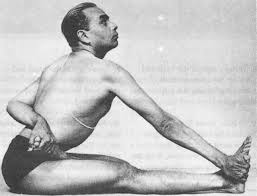

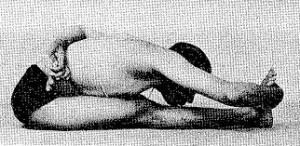

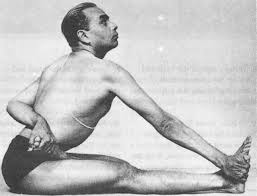

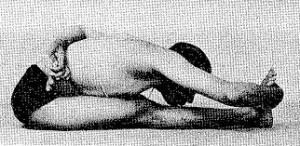

How can us bipedal humans utilize this  amazing coordinating capacity? This dynamic integration is a key action in the yoga of B.K.S. Iyengar, and can be seen in how he presents all of the forward bends in “Light on Yoga”. Ardha baddha padma pascimottanasana is just one example, but they all begin with anterior extension by opening the yin conception vessel, which is a posture in and of itself.

amazing coordinating capacity? This dynamic integration is a key action in the yoga of B.K.S. Iyengar, and can be seen in how he presents all of the forward bends in “Light on Yoga”. Ardha baddha padma pascimottanasana is just one example, but they all begin with anterior extension by opening the yin conception vessel, which is a posture in and of itself.

The forward bend then emerges in the opening/yielding of the yang, back body, governing vessel. These are not spinal muscle actions but pranic/organic releasing in the deep interior structures of the body. Iyengar makes advanced actions look simple, here heart and hara in perfect harmony. But they are not, unless you are a dog!

All yoga beginners know the cat-cow pose which, like the forward bend process of Iyengar, mimics the running action of the dogs through the spine. Unfortunately, as humans, we have less than helpful tail and challenging connection from core to neck and skull. Because of this, and cultural reasons as well, in extending, instead of opening the yin anterior body, we tend to overly contract the ‘yang’ spine (the Governing Vessel or Du Mai), especially the lumbar and cervical regions. Correspondingly, in flexion, instead of softening the yang spinal muscles, we tend to compress the yin fluid body (conception vessel – ren mai).

know the cat-cow pose which, like the forward bend process of Iyengar, mimics the running action of the dogs through the spine. Unfortunately, as humans, we have less than helpful tail and challenging connection from core to neck and skull. Because of this, and cultural reasons as well, in extending, instead of opening the yin anterior body, we tend to overly contract the ‘yang’ spine (the Governing Vessel or Du Mai), especially the lumbar and cervical regions. Correspondingly, in flexion, instead of softening the yang spinal muscles, we tend to compress the yin fluid body (conception vessel – ren mai).

We must learn to awaken the intelligence/dynamic presence of the organs and connective tissue structures in the core of the body, where the coordination in running takes place as our primary support system for the human upright posture. From an evolutionary perspective, this is where the oldest embodied wisdom is stored. We were a gut tube long before we developed a spine and limbs.

A Detailed Inner Anatomy Lesson

We will include both Daoist and western anatomy in the presentation. The key region for integrating flow between the middle and lower dantiens, known as the middle burner in Daoism, includes the liver, gall bladder, stomach, spleen and pancreas, as well as all of the ligaments that hold it all together. These organs are below the diaphragm, but inside the volume of the ribs. The upper burner is the torso above the diaphragm, the lower burner the rest of the abdominal organs including the kidneys. Sometimes the small intestine is included in the middle burner because the upper part, the duodenum, is intimately connected to the stomach and pancreas. We can visualize the three burners as the process that organizes and balances the fire and water elements in the body.

The diaphragm and heart are the primary movers of the energy flow through this space and the diaphragm especially in the movements of the body through space. The diaphragm is intimately connected to the psoas muscles thus linking the legs to breathing. (The integration of breathing and walking is a basic principle in Ida Rolf’s work). So, surprise, surprise, breathing is primary. In the dogs, and other quadrupeds, the diaphragm and organs are vertically suspended downward from the horizontal spine by ligaments and have tremendous freedom of movement. The diaphragm is ligmentously linked to liver, stomach and spleen below and the heart above. As bipeds, we humans carry a lot of vertical compression in our spine, diaphragm, ligaments and organs, inhibiting energy flow. Finding our vertical plumb line, sitting and standing is a key component to helping the relieve compression.

A subtle approach to softening and opening this region uses the breath and comes from Bonnie Bainbridge Cohen’s explorations of the Daoist ‘Embryological Breathing“, and this will be our practice. Watch this video clip and hear how Bonnie describes ‘allowing the breath to emerge from behind the stomach in the omental bursa’, also known as the lesser peritoneal sac depicted in turquoise in the diagram. She contrasts this with more traditional abdominal breathing which primarily engages the lavender greater peritoneal sac. Observe how the lesser sac divides the greater into a front and back, so it puts you in the center portion of the abdomen. Bonnie also refers to the epiploic foramen, where the lesser and greater sacs are linked, which can be seen below.

Now it is very important to know that the volume of the peritoneal spaces depicted in the first diagram are greatly exaggerated. The organs take up most of the space. This is more obvious in this transverse section, taken at the top of the region. What is difficult to see is is that these sacs are the micro-space between two layers of the peritoneum, the continuous membrane which lines the abdominal/pelvic cavity, covers the abdominal organs, and links with various ligaments to provide them a structural support.

The two layers are the parietal peritoneum lining the inner side of the abdominal wall and the visceral peritoneum which has turned inwards to surround most of the abdominal organs. The organs that are surrounded are called intraperitoneal and include stomach liver and spleen. Organs not surrounded by the visceral peritoneum are called retroperitoneal and include kidneys, pancreas, duodenum, oesophagus, ascending and descending colons, and rectum. These greater and lesser sacs, actually very narrow spaces, are usually filled with a small amount of lubricating fluid to help sustain the mobility of the organs in relationship to each other.

Notice how deep into the core of the body this lesser sac space is, and also how it is right in front of the aorta and inferior vena cava. Notice the retroperitoneal kidneys are even further posterior and very close to the outer spinal muscles. A lot of tension is carried in the kidney region because of our overuse of the large spinal muscles just behind the kidneys. We will comeback to an important kidney-lung relationship in a subsequent post. One more thing to note in the cross section is the green costodiaphragmatic recess. This elusive space separates the ribs and diaphragm and all subtle work with the breath has to eventually flow through and open this to further liberate the diaphragm.

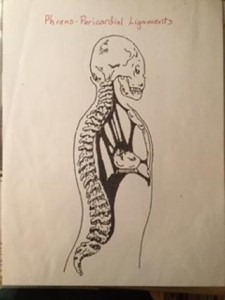

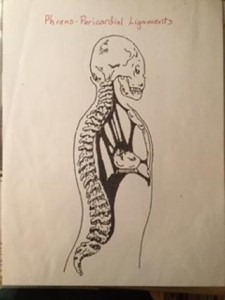

Speaking of the diaphragm, (phreno comes from the Greek root word for diaphragm) there are more ligaments that connect this middle region to the upper burner and these are shown on the left. The phreno-cardiac ligaments connect the heart to the sternum, diaphragm, spine and these are continuous with the ligaments below the diaphragm. If you look carefully at the transverse section, you can see the diaphragm looping around the spine right where the aorta passes through it. These pictures are here to help you navigate/visualize these deep inner spaces when we dive into the practice. Much thanks to the web site, Teachmeanatomy.info and Caryn and Kevin for the drawing of the ligaments.

Speaking of the diaphragm, (phreno comes from the Greek root word for diaphragm) there are more ligaments that connect this middle region to the upper burner and these are shown on the left. The phreno-cardiac ligaments connect the heart to the sternum, diaphragm, spine and these are continuous with the ligaments below the diaphragm. If you look carefully at the transverse section, you can see the diaphragm looping around the spine right where the aorta passes through it. These pictures are here to help you navigate/visualize these deep inner spaces when we dive into the practice. Much thanks to the web site, Teachmeanatomy.info and Caryn and Kevin for the drawing of the ligaments.

On to the Practice

The secret is to embryological breathing is to eliminate all effort and tension. It is a letting go into a natural softening and opening that takes on a life of its own, like the embryological development process, outside the will power. Sounds a lot like meditation practice! Begin lying down with legs supported in any of a number of ways:( knees bent-feet on the floor: knees lifted with bolster or blanket: lower legs up on the seat of a chair).  Relax and allow a few regular breaths to settle the system. Notice if abdominal breathing is your normal breath. Ideally it is, as this is relaxing, like a baby breathing. Chest breathers often have a constricted diaphragm and some level of anxiety as the norm. (Pranayama breathing is a whole other ballgame.)

Relax and allow a few regular breaths to settle the system. Notice if abdominal breathing is your normal breath. Ideally it is, as this is relaxing, like a baby breathing. Chest breathers often have a constricted diaphragm and some level of anxiety as the norm. (Pranayama breathing is a whole other ballgame.)

Visualize the space behind the stomach (the lesser sac) and allow the breath to emerge from and through here. This is much quieter than abdominal breathing, with much less effort. Allow the breath to take on a life of its own. It is not about controlling the breath willfully. If you find yourself tensing through effort, back off and wait a few minutes. Then begin again. Like our sitting meditation practice, patience and a quiet presence are the key. As you allow the breath to flow, it may start to subtly move in all sorts of directions, through all sorts of tissues, through the spaces between layers, in anywhere or everywhere in the body. Let your attention be on the sensations, without trying to manipulate or control them. This is a very yin practice; feeling, listening, noticing and letting go more and more. Patanjali, in his second sutra on posture, PYS II-47, says “keep letting go of effort and allow the cosmic wisdom to flow”.

Once you get a feel for this, you can take the practice into any pose where you can stay alert and relaxed, allowing the pose to flow. Restorative postures are perfect. Supported bridge pose, in any variation, is excellent as it helps you experience the inner opening of the chest as a flow from within, rather than from spinal/muscular effort. Imbalances in the neck and throat, as seen here, can be explored as well by allowing the oesophagus to soften away from the trachea. Some extra height under the shoulders might be helpful here.

Once you get a feel for this, you can take the practice into any pose where you can stay alert and relaxed, allowing the pose to flow. Restorative postures are perfect. Supported bridge pose, in any variation, is excellent as it helps you experience the inner opening of the chest as a flow from within, rather than from spinal/muscular effort. Imbalances in the neck and throat, as seen here, can be explored as well by allowing the oesophagus to soften away from the trachea. Some extra height under the shoulders might be helpful here.

Seated twists also work if you can quietly sustain the double spiral action (right and left). Supported backbends, supported forward bends … be creative. Just remember Patanjali’s instruction: “keep letting go of effort and allow the cosmic wisdom to flow”. Finally, take it into your sitting meditation as another ‘seed’ of attention. By resting in stillness and simultaneously being present to the subtle breathing, the breathing begins to teach you. Both of the spiritual instincts are present, informing each other. Feel the radiance (heart) and the stillness (hara) embracing each other, moment to moment, in the timeless dimension of your True Nature.