Fun with the skandhas ? Are you kidding! Yes! No! … We have to have sense of humor about the human condition; otherwise we would all be nuts, because it is not always easy and not always fun. Sometimes life can be terrifying.

One of the problems for spiritual ‘seekers’ is that we tend to have a fantasy view of enlightenment/awakening and continue to compare our immediate experience to this fantasy. Nothing more frustrating and depressing then this side trip along the path. Observing the skandhas in action, just as they are, is seeing the human condition up-close and personal. No fantasy needed. Reality speaks. But keep your sense of humor to balance the inevitable anxiety/fear/terror that arises!

(For an intro to the 5 skandhas, see the earlier post linked here.)

The term skandha is a Sanskrit word means heaps or aggregates and refers to the various components of what we refer to as ‘consciousness’. In fact, the word ‘consciousness is used to describe the fifth aggregate, the integrated expression of the first four. The skandhas are not added together as much as entwined realms of experience. From simple to complex the five skandhas are: (1) the basic encounter of the spirit with the world of form at incarnation: (2) the immediate resonance with the world of form through sensation/perception; (3) an impulsive response/action to the sensation/perception;

(4) the story/memory/plans, concepts and schemes that organize our impulses in our relationship to a complex world; (5) the personality/egoic structure as an integrated entity.

We need the skandhas to function in the world, but they need to be functioning from wholeness, and not a sense of separation. Healing them is the goal of an embodied spiritual practice.

Skandha 1. The unbounded spirit incarnates into the limitations of the human form and the arrival into this realm creates a bit of a shock. There is a cosmic imperative for life to continue and flourish and to do so, it must survive. In an impermanent world, this is no simple matter. Thus fear is an inevitable and necessary component to the energy field of this new being. It needs to be able to identify danger and respond accordingly. However, the skills to do so have to evolve over time and in the beginning, the new being is totally dependent upon its caregivers. And the caregiviers are not always present and available, or even conscious of their role. This is especially true in utero.

In utero, the soul being is immersed in the physiological and emotional state of the mother and the emotional stability of her immediate environment. Any stress, fear, anxiety or trauma happening to the mother is immediately passed on to her unborn child, who, at this point in time, has no sense of a separate self. This comes much later. There is certainly no time, presence or maturity to quietly reflect on the current condition, so these fears become encoded in their tissues. If we look even more deeply, we can trace the traumas of the mother and father back through the generations, just as we can trace the genes.

Fortunately, the healing process usually begins immediately as well, as when (or if ) there is unconditional love coming through the mother from one of both parents, a nest of non-dual wholeness is created, and the emerging pre-natal being can temporarily relax and let go into the flow. The challenges and complexities of life doesn’t usually let these moments last very long.

The intensity of birth and the birth process, unfortunately sets up another set of traumas for this new being, and with the cutting of the umbilical cord, true separation or ‘aloneness’, arises. The biblical metaphor for this stage is Adam and Eve being ejected from the Garden of Eden for the ‘crime’ of becoming self-aware. A separation occurs, one is naked and alone in the world, and the life journey begins. Because at this stage in the infant’s development there are no words, ideas or concepts attached to the fear, the fear is absolute and primal. This is the wonderful world of the first skandha. This primal fear can be transformed and healed and this is the core of an embodied spiritual practice.

As in the pre-natal world, unconditional love from one or both parents, and others throughout life holds the space of wholeness and healing, but in life the traumas also keep coming. The word trauma is used here in a general sense to describe any experience that reinforces the feeling of being separate and alone and strengthens the egoic structures that are built on the foundation of separation. The acute trauma of violence is an extreme example of this and does far more long lasting damage than the smaller ones, but thousands of small ones add up in their own way.

In PTSD language, an embodied being’s response to this primal fear is to contract around the place where the fear localizes, (usually the heart and 1 or more of the chakras, or organs) and then to dissociate to escape the pain of the contracted fear. In dissociation, we ‘leave the body’, or more accurately, cut ourselves off from what the body is telling us. The first skandha is called “ignorance of form” or just ‘form’. Spirit, through its connection with its expression in the world of form known as ‘soul’, has to figure out how to integrate the reality of impermanence into its moment to moment experience.

As more mature beings encountering this primal fear of impermanence * in our practice, or in life, we can recognize that it arises because we have ‘forgetten’ that form and the formless are one, not two, and we have become ‘lost’ in the world of abstract thought that was created in the next few skandhas. To heal is to awaken to our True Self as unconditional love and unbounded spaciousness, spirit and soul, which is the source/ground of all the sane and crazy stuff we humans experience. * (This primal fear is known as abhinivesha, one of the 5 kleshas mentioned in Buddhism and Patanjali ( sutras II-2 – II-12))

The second skandha, vedana, is usually translated as feelings, but this skandha is about pure sensation and perception, before labels, judgment or interpretation arise. Emotions arise in the third skandha. The embodied being feels/hears sound, perceives tactile vibrations through the sense of touch, sees light, smells the odors of its environment, and tastes whatever it can get into its mouth. We live in a world rich with sensation, most never reaching the conscious level. Psycho-tropic substances highlight how much we miss because our ‘doors of perception’ are often very limited. There is a survival purpose to this, of course, as too much sensation can overwhelm the nervous system. Spiritual training helps expand our capacity to take in the vast majesty of creation safely. As Arjuna discovered in chapter 11 of the Bhagavad Gita, absolute fullness is not so easy to digest! The second skandha involves life’s moment to moment encounter in the present moment, in and with the world of form or what Samkhya and Patanjali call Prakriti. A mature mindfulness practice takes us here and helps us find a stable ground. (See PYS I-12 – I-14)

The third skandha, impulse is where craving and aversion are born in response to the sensations and perceptions that arise and the underlying fear of impermanence. These sensations/feelings of the second skandha are quickly divided into ‘likes’, ‘dislikes’ and neutrals. This is totally natural and desirable, up to a point. To survive, the being needs to move towards safety, healthy food, water and air and away from danger. To grow and evolve, we need to seek out teaching and lessons that nurture our higher selves and avoid situations that drag us back into unconscious pathology.

Unfortunately, the sense of being ‘separate’ can distort a healthy action. The likes lead to craving, the dislikes to aversion and the neutrals to indifference. This separate ‘me’ begins to experience the world through these three lenses and impulsively reacts when triggered. Healing and growth are ignored for immediate gratification of the unconsciously terrified egoic self. ” I want my wall. I have to have my wall.” Not to point out the obvious, but we all have our moments like this. The magnitude of the delusion and the damage caused by Trump are extreme, but we are all needing to wake up to our own unconsciousness.

This stage is often described by the action of The ‘Three Poisons’ of Buddhism. These are often translated directly from the first three (of five) kleshas (see sutras II-2 through II-10 in Sadhana Pada of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras), as avidya or ignorance, raga or craving/grasping, and dvesa or aversion/avoiding/hatred. (The other two kleshas are asmita or confusion about the ‘I’, and abhinivesha or fear of death.) Raga and dvesha, grasping and avoiding are both expressions of avidya/ignorance and are the first two poisons in action. Frank Ostaseski pointed out in his book, “The Five Invitations”, and I agree fully, that in our moment to moment lives, distraction is really the third poison. Avidya comes immediately in the first skandha. So we will call distraction as the third poison.

In “The Network of Thought”, consisting of talks from 1981, Krishnamurti describes the trap of distraction. He observes that as humans begin to have more and more leisure time, are they “going to be absorbed in the field of entertainment? … Or are they going to turn inwardly, which is not entertainment but something which demands great capacity of observation, examination and non personal perception. These are the two possibilities. The basic content of human consciousness is the pursuit of pleasure and the avoidance of fear. Is humanity going to increasingly follow entertainment?” One hopes these ‘Gatherings” are not a form of entertainment.” (The Gatherings’ are Krishnamurti’s famous public talks, many of them given here in Ojai.)

Distraction is a very common expression of the third skandha, ‘impulse’, where our moment to moment strategies to avoid the locked up fear and pain mask as something ‘useful’. Entertainment is a tricky example of this, as one can be ‘entertained’ while abiding in a place of wholeness, and experience a sense of joy, delight and learning in the creativity of Mother Nature, or possibly writers, artists, athletes or entertainers. So we are not saying the entertainment is a problem. But if its pursuit stems from a forgetting of our True Self as infinite Love and leading a life of continuously avoiding the inner pain and conflict we all carry around, then that is unhealthy, from a spiritual perspective.

Impulsive behavior is just that, so the emerging ‘egoic self’ needs to organize these impulses, crave, avoid, distract, into coherent action. Therefore, the fourth skandha, concept, develops, where we create memories and habits, concepts, and strategies that enable us to live our lives within a coherent framework which may or may not be based on delusion. All of the mental processes oof the first four skandhas, taken together as they arise moment to moment, comprise the fifth skandha, consciousness.

In “The Untethered Soul”, a beautiful and powerful book on the enlightened state by Michael Singer, chapter 11 is titled ‘pain, the price of freedom’. Without using the term ‘skandha’, he nails the process of the skandhas precisely. The chapter begins…

In “The Untethered Soul”, a beautiful and powerful book on the enlightened state by Michael Singer, chapter 11 is titled ‘pain, the price of freedom’. Without using the term ‘skandha’, he nails the process of the skandhas precisely. The chapter begins…

” One of the essential requirements for true spiritual growth and deep personal transformation is coming to peace with pain. No expansion or evolution can take place without change, and periods of change are not always comfortable. Change involves challenging what is familiar to us and daring to question our traditional needs for safety, comfort and control. This is often perceived as a painful experience.

Becoming familiar with this pain is part of your growth. Even though you may not actually like the feelings of inner disturbance, you must be able to sit quietly inside and face them if you want to see where they come from. Once you can face your disturbances, you will realize that there is a layer of pain seated deep in the core of your heart. This pain is so uncomfortable, so challenging, so destructive to the individual self, that your entire life is spent avoiding it. Your entire personality is built upon ways of avoiding it. Your entire personality is built upon ways of being, thinking, acting and believing that were developed to avoid this pain.”

This ‘personality’ Michael Singer describes is the ‘Network of Thought’ of Krishnamurti,  and the action of unhealthy skandhas. It takes over the mind field and spins a web of delusion using grasping, avoiding, or distracting. The mind demands something to do, so it can avoid the existential terror, and at the same time validate its own existence. It uses fear to create a smokescreen so the reality and perceived pain of emptiness cannot be seen. (Sounds like Trump and his demand for a wall! Spirituality and politics are inextricably intertwined.)

and the action of unhealthy skandhas. It takes over the mind field and spins a web of delusion using grasping, avoiding, or distracting. The mind demands something to do, so it can avoid the existential terror, and at the same time validate its own existence. It uses fear to create a smokescreen so the reality and perceived pain of emptiness cannot be seen. (Sounds like Trump and his demand for a wall! Spirituality and politics are inextricably intertwined.)

A somatic meditation practice offers an opportunity to go back into the body, being present to the pain residing there and just holding it in loving kindness, like a parent would do with a suffering child. Bonnie Bainbridge Cohen, in the Embryology Workshop I attended last August, described bringing your attention to the place of interest and staying there (samyama) as the only action (yang) required. The innate wisdom of the body does the rest (yin). Being this receptive is not easy in a culture where the yang-doing dominates. The restless mind wants to ‘do something so it can avoid actually feeling the intensity of the stored pain.

Pschotherapist and spiritual teacher John Welwood coined the term ‘spiritual by-pass’ to describe the ways in which we can use a ‘spiritual practice’ as a distraction from this deep unresolved pain. I believe this is a natural outcome of our yang culture which is so invested in ‘doing’ the practice’ that there no space or time for pausing, listening, waiting or allowing is created. This is why slowing down and feeling the moment to moment reality of the soma is crucial for practice.

Practice

Of course, to feel and experience the skandhas in action, we need a meditation practice, or at least the capacity to be a still and silent witness to your own mental movements Patanjali calls the citta vrittis and how the soma/body responds to these movements. Sitting is the best way, and if your practice matures, you will be able to keep healing the skandhas as you go throughout your day. Find a comfortable pose, balanced and relatively relaxed. Begin the mantra: Pause – Relax – Open – Allow.

For a beginner in meditation, both the body and mind are infinite sources of distraction. Sitting can be painful for a novice in embodied presence. Use a chair, cushions for support, a wall, (not that one !) or anything that allows you to relax enough to begin to feel and follow your breath. All it takes is one conscious breath. Just one. Then you begin again. Relax, find the breathing and follow it in and out, not trying to change anything. Just receiving.

Even after the body becomes relaxed enough that the urge to immediately get up and escape the discomfort, following the breath is still very challenging. Our attention usually wanders off to some’thing’ else that is happening, probably thoughts or sensations. In that case, stay with any of the physical sensations as they come and go (2nd skandha), not the thoughts or stories (skandhas 4 and 5). After a few moments, return to the sensations of the breathing. Repeat. when you discover the mind has wandered because of the unconscious pull of the third skandha, rejoice in your discovery as this is what awakening is all about, and gently and compassionately bring your attention back to the breathing.

This process is known as ‘samyama‘, described in the third chapter of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras. Samyama is the simultaneous practice of limbs 6, 7 and 8 of ‘Ashtanga Yoga: dharana – bring your attention to the point of your attention, hear the breath; dhyana – remain there through disciplined resistance to the impulsive desire to wander; samadhi – remaining there effortlessly because you are totally absorbed in the process. Samyama practice recognizes that you will be distracted sooner or later and ask to just begin again, over and over, compassionately and kindly.

If the breath can relax and you can stay in the flow, begin to notice the natural pauses that appear. The pauses are portals to what might be called ’emptiness’, groundlessness, or ‘no-thing’. A taste of this may be temporarily relaxing, but in the beginning our attention cannot find ‘ground’ there and inevitably returns to ‘something’, as opposed to ‘no-thing’. Rarely, the primal fear may arise, as a PTSD moment. If this happens, Pause, relax, bring the breath down into the lower dantien. If it is too intense, get up and move to keep the qi flowing

If your breathing can stay relatively relaxed and easy, try to let your attention rest in the pauses and let the breath fade into the deep background. Feel the ’emptiness’ as a vast opening into larger dimensions of consciousness. Do not try to grasp anything. Pause – relax – open – allow. If your ‘mind’ will not let this happen, slow things down if possible and notice the process of the skandhas. Dharana … dhyana …

For most of us, the core of the practice is continually returning to skandha 3 when you realize that the mind has wandered away. In the beginning, it happens so fast, we do not notice. We just suddenly realize, oh, my mind has wandered. With gentleness and humor, bring your attention back to the breathing. If distraction (the vikshipta mind described by Vyassa in his commentary to the very first of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras) is strong, as it is for most of us for a long period of time, the usual instruction is to give the mind something regular and repetitive to follow.

The breathing is the most common ‘seed or bija‘ to use, but it can be a simple mantra or phrase that is repeated over and over again. A favorite of mine is from Thich Nhat Hahn: ‘Breathing in, I know I am breathing in. Breathing out, I smile.” Counting the breaths to 10 and then repeating is another simple way to focus attention. This is dharana – dhayana of the 8 limbed Astanga Yoga of Patanjali, preparation for samadhi and deeper states.

Perhaps the distraction is not so subtle. Maybe you are jsut settling in when the neighbors car alarm goes off. Or you forgot to turn your phone off and it starts beeping or ringing. A simple sensation (skandha 2) evokes aversion. Or perhaps you can notice the sound, and notice the psychological reaction to the sound, or the physiological/somatic reaction to your psychological reaction, from a space of open curiosity. Or maybe some tasty smell wafts your way from the kitchen and you think, ‘I want some of that. How much longer do I have to sit here. By the way, that reminds me of a dinner we had ….blah blah blah .. oops …lost in thought…pause, relax, open and allow.

If you are experiencing some mild pre-natal PTSD, you are meeting the first skandha. This seems to be a common occurrence in the world of spiritual practice these days.The trauma of gestation and the birth process is stored deep in the non-conscious levels of the mind and long sustained practice of opening and unfolding eventually gets us there. Working through and healing this trauma somatically is a major goal for those of us in the evolutionary field.

When PTSD kicks in a stronger form, it is more then just simple aversion. It is acute panic in the nervous system with terror and dissociation fighting, like trying to jam the brake pedal while the car engine is racing at 6,000 rpms. If you have had some experience with Peter Levine’s Somatic Experiencing, you know the first step is to identify the present moment: this is PTSD in action. It is a somatic memory arising in the present moment and I am perfectly safe and totally loved right here right now. This is called changing the narrative. Then call upon your resources that you have developed in your home practice; Pause, get up and move to keep the qi flowing. Get out into nature if you can. Feel where in the body you feel the ‘freeze’ or closing down and invite the breath to soothe this area. Repeat a mantra. Find someone to help hold the space.The body naturally wants to complete this experience, heal and move on. The body will do this if we understand the process, although it will take time.

You should seek professional support with a somatically trained psychotherapist if your resources are totally overwhelmed. Fortunately for all of us, this is a field co-arising and growing with he increasing number of people engaged in spiritual practice.

Just remember, as this vulnerable being, you, me and everyone else, becomes conscious and begins to interact with the world of form, it begins to notice that the nature of the world of form is impermanent and ‘other than me’. It thus feels separate and alone and forgets that the emptiness and the vast groudlessness in the background is actually unconditional love continuously giving birth to form. Duality is born, a certain level of fear sets in and the being contracts. “Make the smallest distinction, however and heaven and earth are set infinitely apart.” (Hsin Hsin Ming)

But ultimately, this is the process of life awakening. We are all held and supported by infinite love and the wisdom of all of creation. Let it all flow through you as you move and are moved through your day. Be the expression of your soul’s wisdom that brought you here in the first place and join in the celebration of the moment.

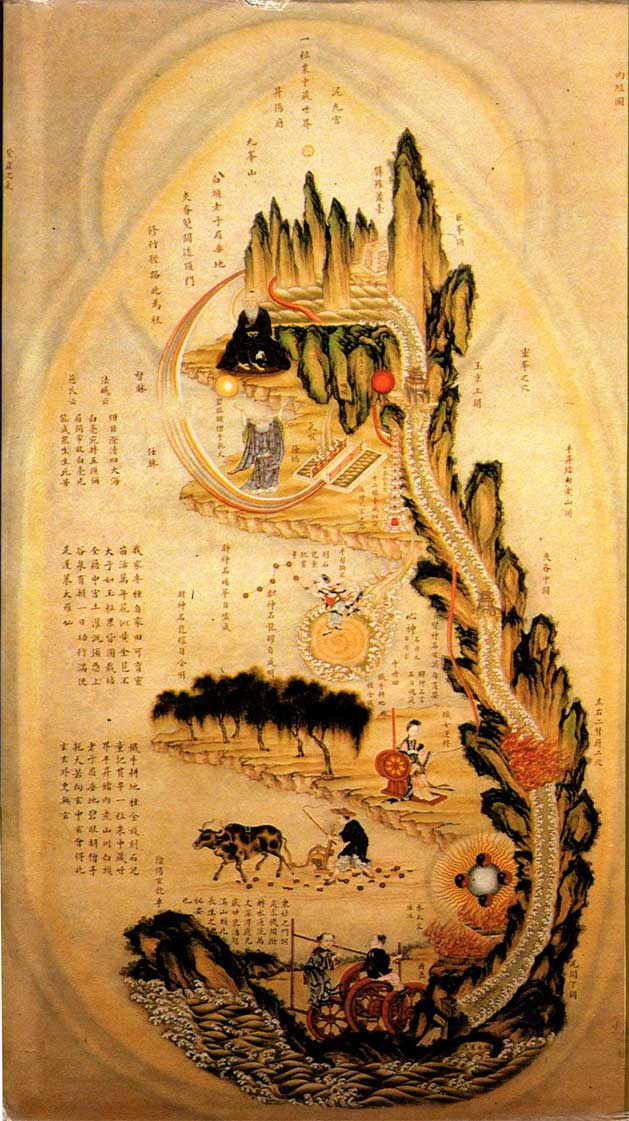

Guidance from my teacher’s teacher, Dr. Jeffrey C. Yuen, an 88th generation Taoist priest from the Jade Purity School, Lao Tzu sect, and a 26th generation priest of the Complete Reality School, Dragon Gate sect.

Guidance from my teacher’s teacher, Dr. Jeffrey C. Yuen, an 88th generation Taoist priest from the Jade Purity School, Lao Tzu sect, and a 26th generation priest of the Complete Reality School, Dragon Gate sect.