The Four Flavors of Love

Some of the greatest advances in modern neuroscience include the expansion of our understanding of the origins and mechanisms of trauma and other modes of emotional disregulation, and the pathways toward healing these wounds. Books by Dan Siegel, Daniel Goleman, Rick Hanson, Allan Schore and others have presented these new insights in a variety ways. * (see below) But, amazingly enough, some of the most profound healing practices for this realm date back to the early Vedic times, 2500 years or so ago. Known as the Brahma Viharas or the four abodes of Brahma, these practices are expressions of the most divine of the emotions, love.

As mentioned in the previous post, practicing the Brahma Viharas is a crucial aspect of preparing the mind and emotions for dealing with death, illness and other challenges and awakening to the depths of love that abide in our natural state. Buddha made these a key aspect of his teaching and the modern Theravadin Buddhists, as exemplified by Western Buddhist teachers Sharon Salzberg, Jack Kornfeld and others have done an amazing job of bringing these practices to the 21st century.

For the yoga students, the ‘abodes of Brahma’, or ‘frolics in God’, as my first Sutras teacher called them, appear in the Samadhi Pada as sutra I-33. They are a direct antidote to the terror of the first skandha and thus are essential for cultivating a strong and open heart. Patanjali doesn’t offer details of ‘how’ to practice the Braahma viharas, so we will introduce those later. The following paragraphs are taken from my Sutras translation and study guide found elsewhere on this site.

I-33 Maitri karuna mudita upekshanam sukha dukha punya apunya vishayanam bhavanatash citta prasadanam.

(The mind becomes purified by) friendliness, compassion, joy, and indifference (equanimity) (respectively) towards those who are successful, suffering, virtuous and unvirtuous.

“Patanjali continues the discussion of eliminating the distractions to samadhi consciousness by addressing the emotions. Because the emotions are so crucial to bringing stability to the mind, this is one of the most important sutras. This sutra also is recapitulated in sutra II-33 where pratipaksha bhavanam, cultivating the opposite mind state, is reintroduced as a means to overcoming negative emotions. These are practices of the heart and are very important in the Buddhist teachings as well.

Friendliness, or loving kindness as it is commonly called in the Buddhist world, is the easiest and most natural positive emotion to cultivate. We all know what it is like to have a friend, to feel the love, warmth and openness that comes when we are with a friend. But also, it is not uncommon to feel envious or jealous over other people’s success or good luck. Practicing maitri (metta or loving kindness) by remembering and recreating these feelings of love, when feeling jealous or disappointed, helps to keep the mind calm and the heart open. And practicing simple kindness in general, like eating good food, nourishes and strengthens the heart. Buddhist teacher Sharon Salzberg has been instrumental in promoting ‘metta practice’, metta being the Pali term for maitri, Pali being the language of the Buddha.

Compassion, karuna, goes right to the heart. When we see others suffering we may either turn away to avoid the depths of feeling, or perhaps take some cruel delight if it happens to be an enemy that is suffering. Choosing to remain compassionate (karuna) in the face of suffering keeps us in our hearts and grounded in being. Being compassionate towards ourselves is also an important and challenging practice. Literally meaning ‘to feel with’, compassion is a profound experience of love and support to another being.

Appreciative Joy: Joy is all around us. From the simple joy of children at play, of lovers in a gentle embrace, to the blooming of flowers and the delight of pets with their owners, life at its core exudes joy. But we do not always feel joyous ourselves so we need to build up a ‘bank account’ of joy. Others may make us feel inadequate, less than worthy, insecure in our selves, if we are prone to engage in comparison. Remembering the joy or delight (mudita) we have felt form others allows us to touch our own joy, and thus strengthen our own joyful, open-hearted self sense. Seeing joy in someone we dislike can also set up feeling of anger and resentment. At a deeper level, life at its essence is joyful. Can we feel appreciative joy at the song of a bird, a flower in bloom, of the night sky?

Equanimity: Seeing suffering and injustice can easily evoke anger and fear. The Sanskrit word upeksha literally means indifference. Here, indifference to suffering and injustice does not mean inactivity or apathy, (See Bhagavad Gita) but a state of non reactivity so that anger and fear do not disturb the mind field with a torrent of negative emotional energy. The Buddhists translate upeksha (upekka in Pali) as equanimity and I like this word much better than indifference. Again the point is to be present to suffering and injustice without falling into emotional turmoil. Then appropriate action (dharma) can be taken with a clear mind and open heart. One of the important lessons from the workshop around care-giving was to watch for ‘pathological altruism’, where our responses to someones suffering are attempts to avoid our own inner suffering and distress that are being evoked. The practice of upeksha can help with this.

Equanimity is the anchor of the four Brahma Viharas as it acknowledges reality. There is suffering. There is injustice. As much as I would love for it all to go away, life is what it is. And this is difficult to accept. Equanimity is the ultimate emotional stabilizer.

The Four Flavors of Love

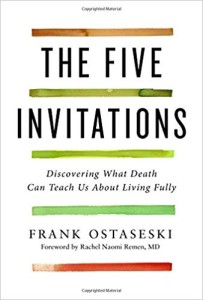

Frank Ostaseski referred to the Brahma Viharas as the ‘Four Flavors of Love’, and both he and Joan Halifax pointed to Sharon Salzberg as the one who impelled them to start working with their own metta practice, which involves repeating specific phrases over and over. The metta phrases are relational, heart centered, and very effective if practiced with sincerity and diligence. Metta practice plants seeds of health and well being into the mind field and opens and strengthens the heart. It is the foundation for working with the other Brahma Viharas.

The traditional phrases have five targets, beginning with yourself. Most of us have a much easier time sending love to others than to ourselves. This is not an egoic action, but one that flows from ultimate mystery. Over time you add: a benefactor or close friend: a neutral person: someone you really dislike: and finally all beings. For the practice to work, it has to be heart-felt, not superficial or dismissive. “Sure, I’ll send love to Donald Trump” (not!) Which is why we keep it simple and easy in the beginning. The most commonly seen phrases are as follows:

- May I be happy.

- May I be at peace

- May I live with ease.

- May I be free from suffering.

- May you be happy.

- May you be at peace

- May you live with ease.

- May you be free from suffering, etc

There are many ways to modify and adapt these so that they are personally meaningful to you. In the Love and Death workshop, we began in a way that was very helpful to me, as the verses Frank taught us were:

May I (we) be safe and free from danger.

May I (we) find happiness.

May I (we) be filled with loving kindness.

May I (we) find ease in our lives.

The root of all painful emotions is fear, so right away we set the intention to be safe, to know we are safe, and to keep reminding ourselves again and again, until we really feel safe. This was the practice I used to help me get to sleep when my PTSD was acting up after the fire last winter. May I be safe! I still use this everyday, sometimes when I am clear, sometimes when I am struggling with my inner confusion and fear. This helps reconnect with our ‘basic goodness’ so we can root ourselves here. You can practice as part of your sitting practice, or anytime in the day when you can pause, relax and go through the phrases several times.

There are similar phrases that can be recited to cultivate karuna, mudita and upeksha.

Karuna:

May you be free of your pain and sorrow.

May you find peace.

Mudita:

May your happiness and good fortune not leave you.

May your good fortune continue.

May your happiness not diminish

Upeksha:

All beings are the owners of their karma; their happiness and unhappiness depends upon their actions, not on my wishes for them.

I care about you, and I’m not in control of the unfolding of events. I can’t make it all better for you.

Things are the way that they are.

An excellent and well detailed resource on working with the Brahma Viharas can be found here: https://dharmanet.org/coursesM/16/bv0.htm.

Books:

Dan Siegel: “The Developing Mind”, “The Mindful Brain”, “Mindsight, “The Mindful Therapist”, “Aware”

Daniel Goleman: “Emotional Intelligence”, “Social Intelligence”

Rick Hanson: Buddha’s Brain” (with Richard Mendius), “Just One Thing”

Allan Shore: Affect Regulation and the Origin of the Self” (very technical, for nerds only, but I discovered some major insights on my shame and panic attacks in this book.)