“I then asked Ezekiel, why he eat dung, & lay so long on his right & left side? he answer’d, the desire of raising other men into a perception of the infinite; this the North American tribes practise, & is he honest who resists his genius or conscience only for the sake of present ease or gratification?

“I then asked Ezekiel, why he eat dung, & lay so long on his right & left side? he answer’d, the desire of raising other men into a perception of the infinite; this the North American tribes practise, & is he honest who resists his genius or conscience only for the sake of present ease or gratification?

The ancient tradition that the world will be consumed in fire at the end of six thousand years is true, as I have heard from Hell.

For the cherub with his flaming sword is hereby commanded to leave his guard at tree of life, and when he does the whole creation will be consumed, and appear infinite and holy, whereas it now appears finite and corrupt.

This will come to pass by an improvement of sensual enjoyment.

But first the notion that man has a body distinct from his soul is to be expunged; this I shall do by printing in the infernal method, by corrosives, which in Hell are salutary and medicinal, melting apparent surfaces away and displaying the infinite which was hid.

If the doors of perception were cleansed everything would appear to man as it is: Infinite.

For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things through narrow chinks of his cavern.”

From The Marriage of Heaven and Hell by William Blake

William Blake, writing in the 1790’s, was probably unaware of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras, but he intuited the need for an inner transformation of perception to awaken humans to the mysteries and sacredness of Divine Creation. Aldous Huxley, Jim Morrison, shamans in many cultures, and many in the baby boomer generation discovered that certain chemical compounds dramatically transformed the inner landscape and opened certain doors to mystical places. As mentioned in the previous post, shamans also use drumming and rattling to induce a shamanic state that opens mystical channels to the infinite. Yogis of old developed an inner science of practices without chemicals or strange side-effects to also open up the mystical world. These practices are called asana and pranayama, or ‘hatha yoga’.

As mentioned in the last post, Patanjali has four sutras addressed to pranayama and these address energetic transitions and phase shifts that Blake was referring to as ‘salutary and medicinal’. They also offer the possibility of preparing the consciousness for shamanic journeying and begin by linking pranayama to asana. Patanjali waits until the Vibhuti Pada to go into the shamanic realms where he unfold various siddhis or mystical powers that arise when ‘samyama’ is turned toward various aspects of nature, but serious hatha yogis learn sooner or later that pranayama can be a gateway.

The Yoga Sutras aim for a ‘masculine – trancendence’ form of spirituality, with the final goal as ‘kaivalya‘, where Purusha separates from Prakriti and rests alone. This, of course is a very important step in the process of awakening, but the modern world requires an integral, non-dual spirituality that requires proficiency in differentiating (not separating) the deep infinite stillness of Purusha, but also proficiency in navigating and integrating the depths of Prakriti, Mother Nature, the world of spirit, and then bringing both together moment to moment, becoming cosmic channels of healing for our planet.

II- 49 tasmin sati shvaasa-prashvaasayor gati-vicchedah praanaayaamah

With that attained, (the mastery of asana) begins the exploration of more subtle life energies through regulating the natural flow of inhalation and exhalation.

Mastery of asana includes what Patanjali describes in the previous three sutras:

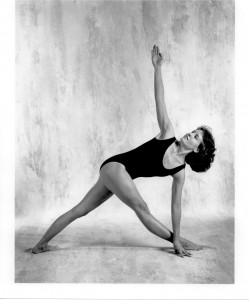

II-46: refining sthira and sukham, aka the balancing of weight and lightness, ground and sky, of movement and stillness. This transforms our bodies into three dimensional perceptual fields of fluid sensitivity moving consciously through the fourth dimension, time. Building perception and learning to balance opposing forces as we move through life, and as life moves through us, are key here.

II-47: Relaxing all effort and becoming absorbed into the cosmic field, aka ananta, or ishvara: In the Samadhi Pada, Patanjali puts a strong emphasis on surrendering into the infinite, Ishvara Pranidhana. This returns here as a deep trust of the biological and cosmological wisdom gained from billions of years of evolution. It is very easy to impose onto Nature as we have been programmed by modern culture to do so. Will power or discipline, known as tapas, abhyassa and vairagyam in the sutras, should be applied to help inhibit our pathological habits, not to impose our will onto Nature.

II-48: Recognizing unity in all duality, so that all layers and levels of yin and yang are seen to be integral to, not opposed to each other. What appear to be opposing forces are actually two complementary forces acting in harmony to allow growth and complexity to emerge. When we find the fulcrums, the places of rest amidst the movements, and can stay there, stabilize our attention there (abhyassa), the next levels of subtle perception can emerge from the deep background. Energetic wholeness is a place of easy, effortless transition of attention through the planes or frequencies open to our attunement. Asana actually has very little to do with exercise, gymnastics, stretching or relaxation, not that that these aren’t fun, or cannot be very useful to creating a reasonable level of health. Asana is phase one of preparation for the deeper inner journeys the old yogis, shamans and mystics had been taking for eons. Pranayama is phase two.

II- 50 baahyaabhyantara-stambha-vrttih desha-kaala-sankhyaabhih paridrsto diirgha-suukshmah

The movements of breath are outward, inward and restrained. Practice involves allowing the stages of the breath to become longer and more subtle as you explore where the breath is felt inside the body, how longs the movements take, and how many cycles you can perform safely.

If we have a strong felt sense of our innate fluidity, breath is felt as waves rolling through the ocean of our body. We can begin to dissolve the stuck places that inhibit even smoother flow of these waves and also begin to allow the natural pauses to spontaneously lengthen. Beginners in yoga would be off doing asana and just feeling the breath in restorative poses, building perception without force. Then inhalation is used to train the ribs shoulder girdle and pelvic girdle to expand and the spine to lengthen form the inside outward. Exhalation is used to train the dome of the diaphragm to stretch up, lifting and widening while the perimeter lines lengthen downward. Imagine the diaphragm as the dome of a parachute, with weight pulling the cords down and a constant upward pressure lifting the center of the dome upward. This uplifting is constant as the heart sits atop the dome.

An average non-yoga trained person inhales by pushing down on the center of the diaphragm, flattening out the dome, and exhales by collapsing the chest down onto the lungs. This inevitably leads to the ‘pear shape’ body you see in many middle age humans accompanied by a diaphragm that moves less and less. For this person, the diaphragm needs to learn how to move more and practices diaphragmatic breathing or belly breath. The abdominal wall moves up and down as the diaphragm disentangles. Hopefully the exhalation comes from the rebounding and restrengthening of the abdominal wall, pushing the diaphragm back up toward its natural dome shape. This type of breathing is also often taught to singers. Yogic breathing takes this several steps further in sophistication

II- 51 baahyaabhyantara-visayaaksepii caturthah

The fourth (in addition to outward, inward and restrained) surpasses the limits of outward and inward.

This suspension of the breath is spontaneous and not the result of the previous mentioned kumbhaka practices. In other words, there is no sense of ‘practicing pranayama’, but of resting in deep neurological stillness. It is from here that we begin to feel the more subtle realms of energy and psychic presence and surrender to the deeper layers of fluid movement. Instead of waves, there are felt as much much slower tidal rhythms that we will discuss in a future posting on craniosacral practice.

TII- 52 tatah ksiiyate prakaashaavaranam

Then the covering of illumination is weakened.

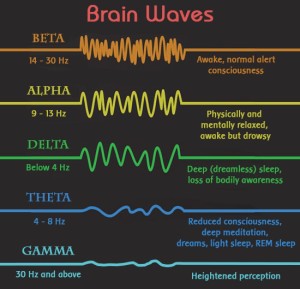

The covering of illumination, the “narrow chinks of his cavern,” is weakened, or cleansed upon the refinement of the art of pranayama. What might this mean from a neuroscientific perspective? An article in Scientific American on the how psychedelics act in the brain states: “In effect, psilocybin appears to inhibit brain regions that are responsible for constraining consciousness within the narrow boundaries of the normal waking state, an interpretation that is remarkably similar to what Huxley proposed over half a century ago.” (Aldous Huxley, is his famous book, “The Doors of Perception” spoke of his experience with mescaline.) In many ways, the waking state restrains consciousness, primarily as a survival mechanism in the modern word. You would not want to be driving a car or operating heavy machinery while having a shamanic experience. You might also have  trouble doing your taxes or writing a legal brief with the mystical channels open. Jill Bolte Taylor, author of ‘My Stroke of Insight” had her left brain citta vrttis nirodhahed by a stroke that left her in an ecstatic state of right brain bliss. But her barely functioning left brain saved her life.

trouble doing your taxes or writing a legal brief with the mystical channels open. Jill Bolte Taylor, author of ‘My Stroke of Insight” had her left brain citta vrttis nirodhahed by a stroke that left her in an ecstatic state of right brain bliss. But her barely functioning left brain saved her life.

Pranayama, being not quite so dramatic, inhibits mind activity by calming down the reactivity of the autonomic nervous system through the balancing of the fire and water elements. In modern culture, the water element is totally neglected, with fire and air predominant. We have a planet full of angry people, full of deluded ideas and belief systems, unable to feel their own aliveness, never mind anyone else’s.

The Practice: Last posting was about refining our perception of the breath. The importance of this cannot be overemphasized. Today we will begin to differentiate ribs from diaphragm, in perception as well as action. You can do this in any seated position, provided you are aligned, upright and comfortable, or lying down in any supported restorative posture. When lying down you gain spinal relaxation, but lose mobility in the ribs. In sitting, you have more mobility in the ribs, but more potential effort in the spinal column.

Step 1: Relax and let the normal breathing settle. Let your heart be light, open and spacious. Get a feel for how you are this moment. Soften all unnecessary tension, especially in the face, neck, and throat. Drop the groins and release the anal mouth. (We’ll get to mula bandha later. Most people hold way too much autonomic tension here and the nervous system cannot shift to the deep parasympathetic tone needed with a tight asshole.)

Step 2: Imagine you have bird wings and let the inhalation begin with a widening of the ribs, as if you were extending your wings sideways. As best possible keep the diaphragm relaxed so the ribs can work. Feel the pelvis widening simultaneously.

Step 3: On the exhalation, let the ribs and wings wait a bit and the belly squeeze the diaphragm up into the center of the chest to initiate the exhalation. As the diaphragm ascends, gradually allow the ribs and wings to release back to center, without the ribs sinking.

Step 4: repeat, slowly, mindfully.

Step 5: As the ribs widen on inhalation, feel the perimeter of the diaphragm, where it attaches to the ribs, being drawn inward and downward, like the cables on a hot air balloon. Imagine the diaphragm connected through the pelvic bones all the way to the feet. Keep the center of the diaphragm always lifting up through the heart, so the heart floats lightly throughout the inhalation.

Step 6: Now on the exhalation, as best possible, keep the ribs expanding, resisting the urge to exhale by dropping the chest. Let the fibers of the diaphragm lengthen up and the dome of the diaphragm expand higher and high upward to push out the air. Over time, the ribs will get more expansive and the diaphragm longer and more elastic. Slowly release the ribs back onto the uplifted diaphragm without dropping the sternum, like a bird drawing in its wings while keeping its chest open.

Step 7: and any time in this process, pause and let the normal breathing return. Notice any tension sneaking in. When you are finished, lie down and digest to sensations. Imprint the felt differences between ribs and diaphragm, and then rest as deeply as possible. Feel the spaces between breaths, thoughts, bones and organs. Let time slow down, space expand and see what arises from the depths of stillness.

In you next asana practice, keep feeling the differentiation. Which poses help open the ribs? Which help stretch the diaphragm? Which compromise the breath?