Happy New Year, 2018

The Thomas Fire, which devastated a large area in Ventura and Santa Barbara counties, sent Kate and myself on a four week journey away from the fire and smoke, and our last stop was a week at the Upaya Zen Center in Santa Fe, where Kate had spent a weekend in November. Zen has, in many interesting ways, woven its way through my life, but I had never formally sat zazen in a zendo. The main teacher at Upaya, Roshii Joan Halifax, had lived in Ojai for many years, and is an amazing woman with a small but deeply engaged group, so it was energizing and inspiring to sit with them and be so graciously welcomed into their community.

One one of the evenings there has a dharma talk and the primary focus centered around a painting by a famous Japanese Zen master and painter, Hakuin. The name was familiar to me, but I wanted to know more about him and came upon the following story. Three things jumped out at me. The first is the awesomeness of synchronicity, where multiple levels and layers and questions and answers come together spontaneously in the moment. Secondly, Hakuin’s journey of healing felt like the path of healing trauma, and the fire had induced and evoked quite a lot of trauma in my own nervous system. And finally, the guidance offered Hakuin was straight from the Tao’ist principles we have been exploring for the past year or so. I have been using the meditation and it has helped me tremendously in getting through some challenging nights.

This story and the accompanying notes come from the web site Buddism Now.

Hakuin Zenji (1689-1769) describes the “Zen sickness” he contracted in his latter twenties and the methods he learned from the recluse Hakuyu in the mountains outside Kyoto that enabled him to cure the ailment.

On the day I first committed myself to a life of Zen practice, I pledged to summon all the faith and courage at my command and dedicate myself with steadfast resolve to the pursuit of the Buddha Way. I embarked on a regimen of rigorous austerities, which I continued for several years, pushing myself relentlessly.

On the day I first committed myself to a life of Zen practice, I pledged to summon all the faith and courage at my command and dedicate myself with steadfast resolve to the pursuit of the Buddha Way. I embarked on a regimen of rigorous austerities, which I continued for several years, pushing myself relentlessly.

Then one night, everything suddenly fell away, and I crossed the threshold into enlightenment. All the doubts and uncertainties that had burdened me all those years suddenly vanished, roots and all—just like melted ice. Deep-rooted karma that had bound me for endless kalpas to the cycle of birth-and-death vanished like foam on the water.

It’s true, I thought to myself: the Way is not far from man. Those stories about the ancient masters taking twenty or even thirty years to attain it—someone must have made them all up. For the next several months, I was waltzing on air, flagging my arms and stamping my feet in a kind of witless rapture.

Afterwards, however, as I began reflecting upon my everyday behaviour, I could see that the two aspects of my life—the active and the meditative—were totally out of balance. No matter what I was doing, I never felt free or completely at ease. I realised I would have to rekindle a fearless resolve and once again throw myself life and limb together into the Dharma struggle. With my teeth clenched tightly and eyes focused straight ahead, I began devoting myself single-mindedly to my practice, forsaking food and sleep altogether.

Before the month was out, my heart fire began to rise upward against the natural course, parching my lungs of their essential fluids.[1] My feet and legs were always ice-cold: they felt as though they were immersed in tubs of snow. There was a constant buzzing in my ears, as if I were walking beside a raging mountain torrent. I became abnormally weak and timid, shrinking and fearful in whatever I did. I felt totally drained, physically and mentally exhausted. Strange visions appeared to me during waking and sleeping hours alike. My armpits were always wet with perspiration. My eyes watered constantly. I travelled far and wide, visiting wise Zen teachers, seeking out noted physicians. But none of the remedies they offered brought me any relief.

Master Hakuyu

Then I happened to meet someone who told me about a hermit named Master Hakuyu, who lived inside a cave high in the mountains of the Shirakawa District of Kyoto. He was reputed to be three hundred and seventy years old. His cave dwelling was two or three leagues from any human habitation. He didn’t like seeing people, and whenever someone approached, he would run off and hide. From the look of him, it was hard to tell whether he was a man of great wisdom or merely a fool, but the people in the surrounding villages venerated him as a sage. Rumour had it he had been the teacher of Ishikawa Jozan [2] and that he was well versed in astrology and deeply learned in the medical arts as well. People who had approached him and requested his teaching in the proper manner, observing the proprieties, had on rare occasions been known to elicit a remark or two of enigmatic import from him. After leaving and giving the words deeper thought, the people would generally discover them to be very beneficial.

In the middle of the first month in the seventh year of the Hoei era [1710], I shouldered my travel pack, slipped quietly out of the temple in eastern Mino where I was staying, and headed for Kyoto. On reaching the capital, I bent my steps northward, crossing over the hills at Black Valley [Kurodani] and making my way to the small hamlet at White River [Shirakawa]. I dropped my pack off at a teahouse and went to make inquiries about Master Hakuyu’s cave. One of the villagers pointed his finger toward a thin thread of rushing water high above in the hills.

Using the sound of the water as my guide, I struck up into the mountains, hiking on until I came to the stream. I made my way along the bank for another league or so until the stream and the trail both petered out. There was not so much as a woodcutters’ trail to indicate the way. At this point, I lost my bearings completely and was unable to proceed another step. Not knowing what else to do, I sat down on a nearby rock, closed my eyes, placed my palms before me in gassho, and began chanting a sutra. Presently, as if by magic, I heard in the distance the faint sounds of someone chopping at a tree. After pushing my way deeper through the forest trees in the direction of the sound, I spotted a woodcutter. He directed my gaze far above to a distant site among the swirling clouds and mist at the crest of the mountains. I could just make out a small yellowish patch, not more than an inch square, appearing and disappearing in the eddying mountain vapours. He told me it was a rushwork blind that hung over the entrance to Master Hakuyu’s cave. Hitching the bottom of my robe up into my sash, I began the final ascent to Hakuyu’s dwelling. Clambering over jagged rocks, pushing through heavy vines and clinging underbrush, the snow and frost gnawed into my straw sandals, the damp clouds thrust against my robe. It was very hard going, and by the time I reached the spot where I had seen the blind, I was covered with a thick, oily sweat.

Using the sound of the water as my guide, I struck up into the mountains, hiking on until I came to the stream. I made my way along the bank for another league or so until the stream and the trail both petered out. There was not so much as a woodcutters’ trail to indicate the way. At this point, I lost my bearings completely and was unable to proceed another step. Not knowing what else to do, I sat down on a nearby rock, closed my eyes, placed my palms before me in gassho, and began chanting a sutra. Presently, as if by magic, I heard in the distance the faint sounds of someone chopping at a tree. After pushing my way deeper through the forest trees in the direction of the sound, I spotted a woodcutter. He directed my gaze far above to a distant site among the swirling clouds and mist at the crest of the mountains. I could just make out a small yellowish patch, not more than an inch square, appearing and disappearing in the eddying mountain vapours. He told me it was a rushwork blind that hung over the entrance to Master Hakuyu’s cave. Hitching the bottom of my robe up into my sash, I began the final ascent to Hakuyu’s dwelling. Clambering over jagged rocks, pushing through heavy vines and clinging underbrush, the snow and frost gnawed into my straw sandals, the damp clouds thrust against my robe. It was very hard going, and by the time I reached the spot where I had seen the blind, I was covered with a thick, oily sweat.

I now stood at the entrance to the cave. It commanded a prospect of unsurpassed beauty, completely above the vulgar dust of the world. My heart trembling with fear, my skin prickling with gooseflesh, I leaned against some rocks for a while and counted out several hundred breaths.

After shaking off the dirt and dust and straightening my robe to make myself presentable, I bowed down, hesitantly pushed the blind aside, and peered into the cave. I could make out the figure of Master Hakuyu in the darkness. He was sitting perfectly erect, his eyes shut. A wonderful head of black hair flecked with bits of white reached down over his knees. He had a fine, youthful complexion, ruddy in hue like a Chinese date. He was seated on a soft mat made of grasses and wore a large jacket of coarsely woven cloth. The interior of the cave was small, not more than five feet square, and, except for a small desk, there was no sign of household articles or other furnishings of any kind. On top of the desk, I could see three scrolls of writing—The Doctrine of the Mean, Lao Tzu, and the Diamond Sutra.[3]

I introduced myself as politely as I could, explained the symptoms and causes of my illness in some detail, and appealed to the master for his help.

Cure

After a while, Hakuyu opened his eyes and gave me a good hard look. Then, speaking slowly and deliberately, he explained that he was only a useless, worn-out old man—”more dead than alive.” He dwelled among these mountains living on such nuts and wild mountain fruit as he could gather. He passed the nights together with the mountain deer and other wild creatures. He professed to be completely ignorant of anything else and said he was acutely embarrassed that such an important Buddhist priest had made a long trip expressly to see him.

But I persisted, begging repeatedly for his help. At last, he reached out with an easy, almost offhand gesture and grasped my hand. He proceeded to examine my five bodily organs, taking my pulses at nine vital points. His fingernails, I noticed, were almost an inch long.

Furrowing his brow, he said with a voice tinged with pity, “Not much can be done. You have developed a serious illness. By pushing yourself too hard, you forgot the cardinal rule of religious training. You are suffering from meditation sickness, which is extremely difficult to cure by medical means. If you attempt to treat it by using acupuncture, moxacautery, or medicines, you will find they have no effect—not even if they were administered by a P’ien Ch’iao, Ts’ang Kung, or Hua T’o.[4] You came to this grievous pass as a result of meditation. You will never regain your health unless you are able to master the techniques of Introspective Meditation. Just as the old saying goes, ‘When a person falls to the earth, it is from the earth that he must raise himself up.’”

“Please,” I said, “teach me the secret technique of Introspective Meditation. I want to begin practising it, and learn how it’s done.”

With a demeanour that was now solemn and majestic, Master Hakuyu softly and quietly replied, “Ah, you are determined to find an answer to your problem, aren’t you, young man? All right, I suppose I can tell you a few things about Introspective Meditation that I learned many years ago. It is a secret method for sustaining life known to very few people. Practised diligently, it is sure to yield remarkable results. It will enable you to look forward to a long life as well.”

“What you must do is to cut back on words and devote yourself solely to sustaining your primal energy.[5] Hence, it is said, “Those who wish to strengthen their sight keep their eyes closed. Those who wish to strengthen their hearing avoid sounds. Those who wish to sustain their heart-energy maintain silence.”

The Soft-Butter Method

“You [Hakuin] mentioned a method in which butter is used,” I said. “May I ask you about that?”

Master Hakuyu replied, “When a student engaged in meditation finds that he is exhausted in body and mind because the four constituent elements of his body are in a state of disharmony, he should gird up his spirit and perform the following visualisation:

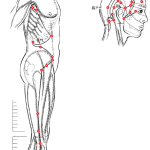

“Imagine that a lump of soft butter, pure in colour and fragrance and the size and shape of a duck egg, is suddenly placed on the top of your head. As it begins to slowly melt, it imparts an exquisite sensation, moistening and saturating your head within and without. It continues to ooze down, moistening your shoulders, elbows, and chest; permeating lungs, diaphragm, liver, stomach, and bowels; moving down the spine through the hips, pelvis, and buttocks.

“Imagine that a lump of soft butter, pure in colour and fragrance and the size and shape of a duck egg, is suddenly placed on the top of your head. As it begins to slowly melt, it imparts an exquisite sensation, moistening and saturating your head within and without. It continues to ooze down, moistening your shoulders, elbows, and chest; permeating lungs, diaphragm, liver, stomach, and bowels; moving down the spine through the hips, pelvis, and buttocks.

“At that point, all the congestions that have accumulated within the five organs and six viscera, all the aches and pains in the abdomen and other affected parts, will follow the heart as it sinks downward into the lower body. As it does, you will distinctly hear a sound like that of water trickling from a higher to a lower place. It will move lower down through the lower body, suffusing the legs with beneficial warmth, until it reaches the soles of the feet, where it stops.

“The student should then repeat the contemplation. As his vital energy flows downward, it gradually fills the lower region of the body, suffusing it with penetrating warmth, making him feel as if he were sitting up to his navel in a hot bath filled with a decoction of rare and fragrant medicinal herbs that have been gathered and infused by a skilled physician.

“Inasmuch as all things are created by the mind, when you engage in this contemplation, the nose will actually smell the marvellous scent of pure, soft butter; your body will feel the exquisite sensation of its melting touch. Your body and mind will be in perfect peace and harmony. You will feel better and enjoy greater health than you did as a youth of twenty or thirty. At this time, all the undesirable accumulations in your vital organs and viscera will melt away. Stomach and bowels will function perfectly. Before you know it, your skin will glow with health. If you continue to practise the contemplation with diligence, there is no illness that cannot be cured, no virtue that cannot be acquired, no level of sagehood that cannot be reached, no religious practice that cannot be mastered. Whether such results appear swiftly or slowly depends only upon how scrupulously you apply yourself.

“I was a sickly youth, in much worse shape than you are now. I experienced ten times the suffering you have endured. The doctors finally gave up on me. I explored hundreds of cures on my own, but none of them brought me any relief. I turned to the gods for help. Prayed to the deities of both heaven and earth, begging them for their subtle, imperceptible assistance. I was marvellously blessed. They extended me their support and protection. I came upon this wonderful method of soft-butter contemplation. My joy knew no bounds. I immediately set about practising it with total and single-minded determination. Before even a month was out, my troubles had almost totally vanished. Since that time, I’ve never been the least bit bothered by any complaint, physical or mental.

“I became like an ignoramus, mindless and utterly free of care. I was oblivious to the passage of time. I never knew what day or month it was, even whether it was a leap year or not. I gradually lost interest in the things the world holds dear, soon forgot completely about the hopes and desires and customs of ordinary men and women. In my middle years, I was compelled by circumstance to leave Kyoto and take refuge in the mountains of Wakasa Province. I lived there nearly thirty years, unknown to my fellow men. Looking back on that period of my life, it seems as fleeting and unreal as the dream-life that flashed through Lu-sheng’s slumbering brain.[6]

“Now I live here in this solitary spot in the hills of Shirakawa, far from all human habitation. I have a layer or two of clothing to wrap around my withered old carcass. But even in midwinter, on nights when the cold bites through the thin cotton, I don’t freeze. Even during the months when there are no mountain fruits or nuts for me to gather, and I have no grain to eat, I don’t starve. It is all thanks to this contemplation.

“Young man, you have just learned a secret that you could not use up in a whole lifetime. What more could I teach you?”

Notes:

1. This was a basic notion in Chinese medical lore. Cf. the statement in the encyclopaedic compilation Wu tsa tsu (Five Assorted Offerings, the section on “Man”), by the Ming scholar Hsieh Chao-che: “When a person is engaged in too much intellection, the heart fire burns excessively and mounts upward.” Torei’s Biography (1710, Age 25) lists twelve morbid symptoms that appeared: firelike burning in the head; loins and legs ice-cold; eyes constantly watering; ringing in the ears; instinctive shrinking from sunlight; irrepressible sadness in darkness or shade; thinking an intolerable burden; recurrent bad dreams sapping his strength; emission of semen during sleep; restlessness and nervousness during waking hours; difficulty digesting food; cold chills unrelieved by heavy clothing.

2. The samurai Ishikawa Jozan (1583-1672) retired to the hills northeast of Kyoto in 1641. His residence, the Shisendo (Hall of Poetry Immortals), is located on a hillside overlooking the northern part of Kyoto. See Thomas Rimer, Shisendo (New York: Weatherhill, 1991). There are several caves Hakuyu is said to have inhabited located in the hills behind the Shisendo.

3. The three books are intended to show Hakuyu’s roots in the three traditions: Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism.

4. P’ien Ch’iao, Ts’ang Kung, and Hua T’o are three celebrated physicians of ancient China.

5. Vital energy translates the term ki (Chinese, ch’i), a key concept in traditional Chinese thought and medical theory. It has been rendered into English in various ways—for example, vital energy, primal energy, breath, vital breath, spirit. Ki-energy, circulating through the human body, is vital to the preservation of health and sustenance of life and plays a prominent part in the methods of Introspective Meditation that Hakuin learned from Master Hakuyu. The “external” alchemy of the Taoist tradition involved the search for a “pill” or “elixir” of immortality, the most important element of which was a mercury compound (cinnabar). Once found and taken into the body, it was supposed to assure immortality and ascent to heaven, commonly on the back of a crane.

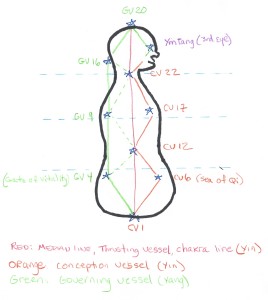

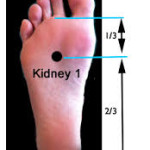

Hakuyu’s instruction is concerned rather with the internal ramifications of this tradition, in which the “elixir” is cultivated in the area of the lower tanden, the “elixir field” or “cinnabar field,” also called the kikai tanden, “the ocean of ki-energy,” the centre of breathing or centre of strength, located slightly below the navel. Hakuin describes the terms in Orategama: “Although the tanden is located in the three places in the body, the one to which I refer is the lower tanden. The kikai and the tanden, which are virtually identical, are both located below the navel. The tanden is two inches below the navel, the kikai an inch and a half below it. It is in this area that the true ki-energy always accumulates.”

(tanden = dantien or elixir field)