From the Patanjali Yoga Sutras:

II- 51 baahyaabhyantara-visayaaksepii caturthah

The fourth (in addition to outward, inward and restrained) surpasses the limits of outward and inward.

II-52 tatah ksiiyate prakaashaavaraanam

Then the covering of illumination is weakened.

II- 53 dhaaranaasu ca yogyataa manasah

And the mind becomes fit for concentration.

From Ramana Maharshi’s Upadesa Saram ( The essence of the Vedantic teachings.)

11: Vaayurodhanaalliiyate manah

Jaalapaksivadrodhasaadhanam

By restraining the breathing, the mind is controlled, like a bird caught in a net.

12: Cittavaayavascitkriyaayutaah

Shakhayordvayii shaktimuulakaa

The mind and the prana are endowed with the ability to know and act respectively. These two are like two branches stemming from one power.

From Swami Dayananda’s commentary to the Upadesa Saram:

“It must be borne in mind that pranayama, controlling the breath, is a technical process and should be done under the guidance of someone who is competent. An easier process is called prana-viksanam, or observing the process of breathing. The mind is given the occupation of watching the breath entering and leaving the nostrils and there is no attempt to change or control the pattern of breathing. The mind gets an occupation in which no deliberation or will is involved. Mind gets absorbed in observing prana which is formless and part of the subtle body. This is much easier and does not involve any complication associated with the pranayama with kumbhaka.”

From “The Way of Liberation” by Adyashanti” (his italics)

“Meditation is the art of allowing everything to simply be in the deepest possible way. In order to let everything be, we must let go of the effort to control and manipulate our experience – which means letting go of personal will. This cuts right to the heart of the egoic make-up, which seeks happiness through control, seeking, striving and manipulation.”

The interlinking of breathing and mind activity, citta vrttis, is well known, both to spiritual practitioners ans well as neuroscientists. Quiet breath equals quiet mind, and a quiet mind is the beginning of meditation. Here we come to the paradox of hatha yoga, especially in the ‘I need to be in control’ modern world. When our body/minds are entangled in patterns of trauma, stress and confusion, how can we bring some stillness and healing to ourselves and others? How can we explore the many lessons yoga offers around healing and wholeness, while simultaneously remaining in a state of surrender to what is? What if ‘what is’ is ‘stressed out’? Now that I am living in one of the major surfing regions in the world, I am finding a very helpful clue lies out on the water.

A surfer is at the mercy of the ocean. Big waves, small waves, no waves, whatever; the surfer has to accept the reality of the moment. You cannot control the ocean. If you are a wind surfer, or kite surfer, you can add wind to the mix. But what you can do is refine your capacity to see and feel the wind and waves, learn how your board and body respond, and allow your body to become one with the whole process. Wiping out is included in the possibilities. You start as a beginner, learn from your experiences, and move on to the challenges that suit your capacity. Surfing is a process of cosmic alignment. The same goes for sailing where the sailor learns to read the wind, water currents, tides and waves, as well as the lines, sails and feel of the boat. In hatha yoga, we are both the sailor and the boat, the surfer and the board, navigating our embodied lives as we sail and surf through cosmic space. This is dynamic meditation, or meditation in action.

In working with the breath, the inner prana is the ocean, a dynamic fluid field of emotions and habits; of heart beat, peristalsis, and respiration; of waves, pulsations and tidal forces. We might even compare the diaphragm to a surf board, although it is way more complex. The surf board links the inner ocean of the surfer to the outer ocean. When the diaphragm is relaxed and riding along with the breathing, there is the effortless surrender that is felt from skin to cells. When the diaphragm is tense, restricted or inhibited, there is fear anxiety and distraction.The yogi cannot feel the inner movements of the prana because of the tension patterns in the nerves, fluids and tissues.

As Swami Dayananda mentioned above with prana vikshanam, and as was mentioned in a previous post, quietly observing the breath is the beginning practice that can last for years. It eventually becomes a basic life skill functioning, 24/7/365.2422, and naturally leads to ‘mindfulness meditation’. This is just being present to what is arising moment to moment, whether on the mat, or in the world. As we enter into more formal pranayama practice, relaxing, feeling and allowing are still the primary practices. Then we can begin to surf.

The Practice: Viloma Pranayama

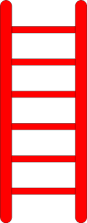

In traditional viloma pranayama, the in-breath and/or the out-breath are divided into several small steps, like walking up and down stairs. There are many advantages to working this way. First, we begin to notice the pauses more clearly because shorter breaths are less stressful and easier to sustain effortlessly. Secondly, we can use the steps to notice different parts of the body. If my in-breath has three steps to fullness, the first step can fill the lower lungs, the second fills the middle, and the third fills the upper lungs. I can learn where in the body I have intelligence, sensitivity and space and where there is restriction. Thirdly, I can begin to differentiate ribs, spine and diaphragm. Because I am moving slowly and deliberately and pausing periodically, I can be more attentive to these areas and notice how they are working.

A whole other level in viloma arises when I learn to use the pauses in different ways. In traditional viloma, the pauses are like mini kumbhakas. You are neither breathing in nor out, but just waiting without tension. The ‘without tension’ part requires a lot of patience and practice and here is where some other options can be helpful.

Option 1: I call this ‘rolling viloma’ and it is the breath that totally changed my understanding of pranayama. Another way to describe it is two steps forward and one step back, two steps forward and one step back, etc. Viloma 1 would be: Inhale 1, 2 and 3 is a slight exhalation, inhale 4, 5 and 6 is a slight exhalation, gradually filling the lungs. It feels like a wave inside a wave, as the pause is now a loop. Then a relaxed, normal exhalation. Viloma II would have a normal or slightly longer inhalation followed by: exhale 1, 2, and 3 is a very slight in breath; exhale 4, 5, 6 is a slight in breath, continuing until the lungs have emptied. The pause is again a loop of energy rather than a stopping.

Option 2: Here, the pause becomes an opportunity to re-balance ribs and diaphragm. As mentioned in a previous post, ribs and diaphragm can work together beautifully, or not. In Viloma, we use the pause to re-adjust the action of each. In Viloma I, where the emphasis is on the inbreath, the pauses are used to recharge the ribs and intercostals and relax the tension in the perimeter of the diaphragm, without releasing any breath. Then normal exhalation. This is a it more challenging than Option 1.

Viloma II, although now the exhalation is emphasized, the pauses are used similarly. The ribs tend to drop too quickly, so the pauses are used to recharge the ribs and inter-costals, like in viloma I. But now, during the pause, the center of the diaphragm is lifted up, stretching into the rib space, so it begins to sit higher and higher in the chest where it belongs. Exhalation ideally stretches the diaphragm, just as the inhalation shortens the diaphragm. The longer the excursion, that is, how far the diaphragm can more between full in breath and full out breath, the easier and more effortless the breathing. Both ribs/intercostals and the diaphragm need to stretch and open a lot. This comes with pranayama, and not prana vikshanam.

Viloma with Mantra or Japa:

(Thanks to Miami based yoga teacher Jodi Carey for this suggestion!)

As viloma has steps or stages, these can be integrated with a mantra. As an example, in Viloma I, the inhalation would be: Om namah shivaya, pause, Om namah shivaya, pause, Om namah shivaya, pause, and the exhalation could be Om. Reverse for Viloma II. The mantras are repeated silently, so it is a japa practice. A simple Om, or Om mane padme hum, or Om shanti shanti shanti are other possibilites. Be creative.

In all pranayama practices, there are certain indicators of strain that need to be monitored. We are trying to be in harmony with healing, not fighting against our habits, and this is not easy. Pranayama is not an easy practice because it requires diligence, patience and honesty.

First: observe the nature of the pause at the end of each exhalation. If it was relaxed, you may proceed with another cycle. If the pause after the exhalation had some excess tension, allow several normal breath to come and go to bring the pause after exhalation to a state of relaxation. Then continue with another cycle. Viloma is very good at easing the transitions after exhalation and is the best pranayama for beginners.

Second: Watch for tension in the face, eyes, ears, jaws, neck and throat. A natural jalandhara bandha, with the brain dropping without collapsing the chest will help if you are sitting. It is like bowing your head to pray. The brain surrenders to the heart without tensing the throat. Also, the mechanics of breathing do not need any help from head, neck or shoulders. If the strain continues, just watch the breath.

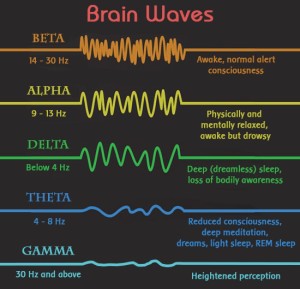

Third: Monitor the felt sense of pressure in the brain. In pranayama, and all healthy breathing, the brain ‘exhales’ when the lungs are inhaling and the brain ‘inhales’ when the lungs are exhaling. This is subtle, and not subtle at the same time. If the brain does not relax on the in breath, just watch the breath. Be patient.

Fourth: After practice, lie down and relax, letting the practice be digested by the nerves. Enjoy the stillness. Let it seep into the depths of the cells. Be meditation. Be.