Notes from Boston, April 2019

Only 10 left of the 44 radiation treatments taking place here in Boston. Along with all of your love and prayers, an extraordinarily wonderful group of people at The Brigham and Women’s Hospital, the Dana Farber Cancer Institute, and my cancer club friends here at Hope Lodge, are all taking care of me. A minor set of challenges and annoyances are arising from the accumulation of the radiation, mostly centered around fatigue and bladder confusion, but, all in all, I’m doing just fine. Life wants us to keep growing and evolving, so new challenges are created to keep us focused. (Fill in you own political metaphor here, if you choose!)

Only 10 left of the 44 radiation treatments taking place here in Boston. Along with all of your love and prayers, an extraordinarily wonderful group of people at The Brigham and Women’s Hospital, the Dana Farber Cancer Institute, and my cancer club friends here at Hope Lodge, are all taking care of me. A minor set of challenges and annoyances are arising from the accumulation of the radiation, mostly centered around fatigue and bladder confusion, but, all in all, I’m doing just fine. Life wants us to keep growing and evolving, so new challenges are created to keep us focused. (Fill in you own political metaphor here, if you choose!)

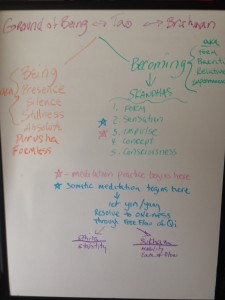

Where is the growth and evolution arising from? From a spiritual perspective, from the “Ground of Being”. As noted in the chart above, the terms at the top: ‘Ground of Being”, Tao and Brahman are interchangeably used to make an attempt to express the inexpressible. ‘Before all duality’ implies time, which is relative. ‘Beyond all opposites’ implies space, also relative. In the world of form, which includes our body/minds, all of creation and anything we put into words, everything appears as part of a pair of opposites. But know that in the depths of silence all duality dissolves and what remains the ineffable mystery. Be there. You are always there already. We have just forgotten to notice. We practice stillness or silence to ‘remember’ who we truly are.

There is no substitute for the practice of silence. There are no techniques, breathing practices or asana sequences that can lead you to what always was, is, and ever shall be. And yet if we do not make a conscious choice to make ‘being in silence’ a priority, the healing power, growth and insight that arises from the stillness will never be fully received. Spirituality grows in the world of paradox and is nurtured in meditation.

In sutra I-3, tada drashtuh svarupe’avasthanam, Patanjali describes yoga as ‘resting in our own true nature’, the unbounded Silence of Being, or Ground of Being, or Tao, and ‘staying there’. I love the word ‘resting’ as it is clearly not about ‘doing something’. Sometimes the word abides is used, as in “the dude abides’. Here the implication is that of finally coming home, recognizing home, and staying home.

As someone who has become addicted to ‘doing’, resting is not easy for me. There are so many layers of mental chatter, conscious and unconscious, that want my attention. My confusion from skandha 1 has left a belief system that says I have to ‘heal’ myself’, and has confused the layers of form that comprise the body/mind with “I’, myself. There is no solution from this perspective. Only an endless chasing after the illusion of ‘finally getting it right’ and an attentional field that never rests.

When we make a conscious choice to practice silence, something else happens. The mental chatter and the physical sensations do not go away in the beginning. And if they do temporarily disappear, they will come rushing back sooner or later. What arises is the possibility of a change in perspective. In the early stages of meditation, there is the cultivation of what is called ‘witnessing’. Whatever arises in awareness, usually thoughts sensations, emotions or an amalgam of all of these, is ‘seen’ and thus recognized as ‘not me’. If ‘I’ can see it, it cannot be ‘I’. We differentiate seer and seen. This process involves the two crucial components of spiritual awakening; attention and identification.

In witnessing, our attention is not drawn to what arises (the seen) but to the process of witnessing itself. We allow what arises to come and go as it will, and also allow our attention to turn inwards, not to thought or the inner sensations, but onto itself, where it spontaneously dissolves into silent unchanging awareness. We begin to notice that attention is the root of self ‘identification’. The more I habitually attend to the world of form, the more my self sense or identity becomes entangled there. When my attention dissolves into silent awareness (this is the meaning of citta vrtti nirodha, sutra I-2) my identification with the world of form also begins dissolve. Here is where we begin to more deeply question just exactly ‘who or what am I?

In sutra I-4, Patanjali describes this crucial piece to the spiritual conundrum: vrtti sarupyam itaratra or (at other times, that is when not in the state of yoga) there is identification with the world of form, the vrttis. Identification is the key. The egoic self, arising in skandha 1, begins to create a ‘me’ or ‘self’ from the likes and dislikes and then this entity evolves through the rest of the skandhas to fill out the egoic self. We make the mistaken belief that what arises is all part of me and therefore I am impelled to respond by grasping (likes), avoiding (dislikes) or ignoring. Grasping and avoiding, and all their behavioral cousins are mentioned by Patanjali in sutra II-7 and II-8, and the whole process we are describing in sutras II-1 – II-17.

In sutra II-11, Patanjali brings in meditation as the means to disentangle the identification process. II-11 dhyaana-heyaas tad vrttayah: Meditation eliminates the changing mind states (created by the kleshas). Meditation, that is, resting in stillness leads to citta vrtti nirodha and drashtuh svarupe avasthanam.

We now add to Patanjali, Mr. Donald Hebb and his famous axiom: ‘neurons that fire together wire together’. Our attentional field sets up neuronal firing patterns that get stronger through repetition. Our attention, identification and power of belief all function in this domain. This is the insidious side of habit. Neuronal energy wants to follow the easiest pathway and when our habitual attention is driven by the unhealthy skandhas, these pathways go through the fight or flight/fear’ center also known as the amygdala. The unhealthy skandhas become stronger and stronger. As the news continues to remind us, this plays out on the cultural level as well as the personal one.

However, meditation practice has been shown to shrink the amygdala and create growth in the neuronal connections of the pre-frontal cortex where we develop the capacity to see from a place of integration, clarity and wisdom. We might say that the buddhi or ‘intelligence’ is the linking of the pre-frontal cortex and with the emotional and spiritual intelligence of the heart heart. Here ‘citta vrtti nirodha‘ is seen as a re-wiring of the brain and its patterns of firing. Resting in stillness is a self-organizing process. Because of the nature and strength of habit, tremendous patience is required. In sutra I-12 abhyasa vairagyabhyam tan nirodhah: Practice and dispassion lead to the resolution (of the dysfunctional mind states). Patanjali lists the two key components of meditation, dispassion and stability.

I-13 tatra sthitau yatno’bhyasah

Practice leads to stable healthy mind states and stillness.

I-14 sa tu dirgha-kala-nairantarya-satkarasevito drdha-bhumih

Stability of mind requires continuous practice, over a long period of time, without interruption, and with an attitude of devotion and love.

Deeply ingrained habits do not go away overnight, whether in an individual or a society. The neuronal connections and cultural fields can be strongly wired, especially if they have been repeated over and over. To lay down new neural pathways and weaken the old ones takes time and patience. Devotion and love are required to make sure the new pathways are healthy and not dysfunctional. It is quite easy to react to an unhealthy pattern by creating another unhealthy one. “”I hate myself for having all this judgment,” is a common thought/vrtti. Learning to gently and compassionately see the thought and recognize it for what it is requires discipline and patience. Meditation practice allows us to see these thought and behavior patterns from a distance, as a witness to them, which is the first step in transforming them.

What we pay attention to receives our energy. By choosing to not react to our thoughts, but just let them come and go, we are withdrawing from them. We are letting them go. This is vairagyam, described in the next sutra. There are many vrttis floating about the mind field that are triggers for suffering, and they keep returning, even if we let them go, if they have strong roots. The ‘heavenly realms and the hell realms are both attractive to the unhealthy skandhas, and attachment to even the heavenly realms is a set-up for more suffering. That is why patience and persistence are the two key supports. Vairagyam is sustaining a healthy and alert immune system for the mind.

I-15 drshtanushravika-vishaya-vitrshnasya vashikara-sanjna vairagyam

The control over craving after any experience, whether sensual, psychological or spiritual, is known as dispassion.

The root of dysfunctionality is craving, the intense desire to acquire or get rid of ‘something’, to create a temporary feeling of wholeness or relaxation. These are emotional or limbic responses, that evoke a threat to our existence. To a self-sense that feels inadequate, there is always something that is threatening, that needs changing. Craving, as we soon find out in life, is a self-perpetuating path of inadequacy and subsequent suffering. Life is what it is happening moment by moment and true happiness is not dependent upon the constantly changing circumstances of life. If I believe that my happiness depends upon this moment being different from what it actually is, I will suffer. Seeing through this delusion is a crucial component of yoga. The true nature of the Self, the unchanging limitless existence and consciousness, (sat – chit – ananda) is undisturbed by any and all possibilities life throws our way.

With the discipline of vairagya we stop believing the craving thoughts, even if they keep arising. No, my happiness is actually not dependent upon getting rid of Donald Trump! This eventually leads to dispassion towards most craving. The subtle forms are dealt with in the next sutra.

The neuroscientific perspective on inhibition offers tremendous insight for yoga students. In Buddha’s Brain” authors Rick Hanson and Richard Mendius describe the capacity to “simply not respond” to limbic (emotional) activity. There is not the inhibiting of the emotional activation which manifests as physiological sensation, but rather inhibiting the next level of neural activity, the story I tell myself that perpetuates the suffering. Repressing emotional content is not healthy on any level, but recognizing it as it arises, positive, negative or neutral, awakens a meta level of awareness. Then I can use skillful means to help the emotional energies move to a more integrated state.

Important note! Vairagyam is not the absence of passion! An integrated self is highly passionate, just not insecure and needy.

I-16 tat param purusha-khyater guna vaitrshnyam

The more advanced form of dispassion involves the full realization of self as the absolute and the dropping away of the most subtle forms of craving and attachment.

see also sutras II – 26, III – 5, IV-29 – 31

In I-16, Patanjali restates I-3, the knower/seer resting in its own nature, as an example of the culmination of refined discipline/dispassion. My mind may generate wants, needs and desires, but I can see their origin and not turn them into issues of survival. I may want an ice cream cone, but getting one, or not getting one is not a big deal in the overall scheme of things. Or, I have been diagnosed with cancer, which is the last thing I want, and the mind wants to rebel. At some point in time, I will face the reality of this and do whatever I can, in the world of form, to help heal. But in any case, I recognize the undying Nature of the Self, and take refuge there.