Yin/Yang and Yoga: On the Nature of Movement and Stillness

“The tao that can be spoken is not the true Tao,

The name that can be named is not the eternal Name.”

In the opening lines to the Tao Te Ching, Lao-tzu immediately points out the impossibility of describing the indescribable. Spiritual revelation is beyond words, ideas and concepts, but is realizable and knowable, through direct experience. But Lao-tzu continues anyway, using poetry to point to mystery, inviting us to jump in and discover the Tao for ourselves. Spiritual practices are like the poetry, inviting us to make the plunge of direct experience of the mysteries of life.

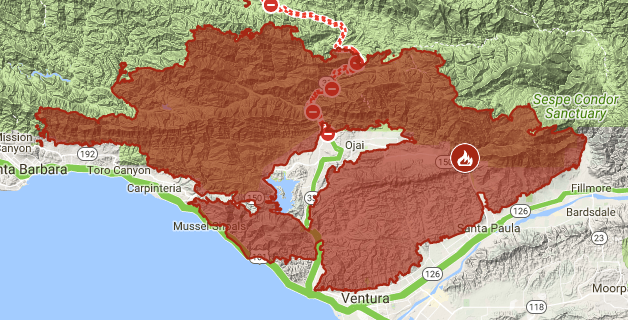

Taoism presents a non-dual model of reality, using the interplay two fundamental and complementary ‘forces’ to create entire universes. By non-dual we the two forces or perspectives, while radically different, are actually mutually inclusive expressions of a singular wholeness. The Taoism uses the terms Yin and Yang, which while very different in nature, are inseparable. There is no pure yin, no pure yang. Distill yin 10,000 fold and still yang will be found. Distill yang 10,000 fold, still there will be yin. Always both in an eternal dance. as shown in the well known image above. Our journey is to feel, explore and express these fundamental qualities in as many ways and dimensions as possible and discover the nature of love and creativity, of compassion and healing, of wisdom and stillness. Later in this post we will look more deeply at some of the nuances of yin and yang in our embodied asana explorations.

Taoism presents a non-dual model of reality, using the interplay two fundamental and complementary ‘forces’ to create entire universes. By non-dual we the two forces or perspectives, while radically different, are actually mutually inclusive expressions of a singular wholeness. The Taoism uses the terms Yin and Yang, which while very different in nature, are inseparable. There is no pure yin, no pure yang. Distill yin 10,000 fold and still yang will be found. Distill yang 10,000 fold, still there will be yin. Always both in an eternal dance. as shown in the well known image above. Our journey is to feel, explore and express these fundamental qualities in as many ways and dimensions as possible and discover the nature of love and creativity, of compassion and healing, of wisdom and stillness. Later in this post we will look more deeply at some of the nuances of yin and yang in our embodied asana explorations.

Our Non-Dual Vision: A Context for Practice:

Most spiritual traditions, in their mature phase, have a non-dual vision. The realization is that there are two clearly different but fundamental perspectives on life, that, like yin and yang, may be differentiated, but are innately inseparable. At the most primary level, these two perspectives are: the experience of ‘Stillness’; and the experience of ‘Movement’. Taoism, as noticed by Lao-tzu, doesn’t offer a word for ‘Stillness’. Tao implies ‘Stillness plus yin/yang as Movement. Other traditions have used words to point to “Stillness” and “Movement’ to help us in our own self-realization and these include: Presence and Love, The Seer and The Seen, Pure Awareness and What Arises in Awareness, Luminous Emptiness or Buddha Nature and Impermanence, Purusha and Prakriiti, Now and ClockTime, Formless and the World of Forms. Beyond words these two Cosmic Views need to be felt, integrated and known intimately to live a fulfilling and spiritual life. For our purposes here, we will call them the masculine, or Presence and the feminine or Love.

From our first perspective, we experience life as continuous change, as non-stop movement. This perspective is the feminine, often called the ‘Seen’, as our sense organs tune into, perceive and respond from this realm. In the Shaiva tradition of India, the goddess Parvati represents this realm as the Divine Mother, the nurturing and loving link that connects all beings and creation through Unconditional Love. All that arises is an expression of Divine Love. Ojai’s own Byron Katie uses this as her primary teaching theme and the title of her first book, “Loving What Is”. When there is harmony and coherence in our lives, this flow is experienced as the infinite expressions of love, including health, well-being, creativity, joy, delight and bliss.

This level is also ‘the flow of time’, of birth and death, of learning and forgetting. Buddhists call this the experience of impermanence. Our survival instincts demand we pay attention to change, so for most, this is the perspective that dominates our attention. Because of our spiritual immaturity it tends to be driven by fear, anxiety and insecurity, and not love and compassion. Then we over-react to life, endlessly chasing pleasure and desperately trying to avoid pain. The slightest inconvenience can begin a seemingly non-stop cascade of negative thoughts and emotions. This is suffering. When integrated with and grounded in the Divine Masculine “Seer’, the feminine love and compassion flow freely and can heal fear, insecurity and anxiety. We can stop, feel the deep stillness of presence and feel the divine love. We can then realize that each moment offers us exactly what we need to keep growing and healing.

The complementary masculine perspective is Stillness, aka absolute stability or the ‘Seer”. This perspective is often completely missed as it can’t be ‘seen’, just as the eyes cannot see themselves, (except with a mirror, which is the metaphor Vedanta uses for its teaching, helping the ‘Seer to recognize itself.’) Represented by Shiva, sitting alone on a mountain top, absorbed in stillness, this masculine point of view offers wisdom as its gift as well as a stable anchor to support us in navigating the challenges of living in a human body. It is unchanging, unbounded and timeless, holding all in infinite stillness. But without the integration with the feminine love and compassion, the wisdom and stability can be cold, heartless and empty. We always need both. This is the non-dual vision, masculine and feminine in an integral embrace of movement and stillness.

We all need to feel stable to function, but our spiritual vehicle, the body-mind-sense complex is in constant flux. In a spiritually immature, non-integrated state, we try to create stability by trying to freeze or fixate a stable ‘self’ or ‘me’ out of the continuous changing world. We do not recognize that we are also, always, grounded in the Absolute Stability of the ‘Seer’. We get con-fused. We forget. This forgetting is the metaphorical fall from the Garden of Eden, the ‘Original Sin” of the Catholics and is the root of all suffering. Life can be painful. There is sickness, pain and death as part of the spiritual journey, but these are not suffering described by the Buddha. Suffering is the forgetting that, in spite of the challenges, we are infinite light, love, compassion and wisdom. Thus we can say yoga is about ‘remembering’ our ‘true nature’ and reminding ourselves again and again when we forget.

If and when we are not grounded in the Timeless, we create unstable identities/small selves/egoic selves/personalities out of bits and pieces of our experience in the world of changing forms and believe them to be the ‘self’ . That is, we ‘identify with’ our thoughts, our bodies, ideas, and beliefs and spend vast amounts of psychic energy battling to keep these unstable structures solid, defending them against other similar, ego driven structures. This is easy to see in others, not so much in ourselves. (Sutra I-4) The concept of no-self in Buddhism points to the fallacy of believing in a fixed sense of ‘self’ constructed by the mind. Sitting practice opens the door to observing this process of ‘selfing’, so it becomes a living reality and not just an idea. We do it all the time. And we can step outside the process, as a silent witness, and watch the show. And learn. And wake up.

these unstable structures solid, defending them against other similar, ego driven structures. This is easy to see in others, not so much in ourselves. (Sutra I-4) The concept of no-self in Buddhism points to the fallacy of believing in a fixed sense of ‘self’ constructed by the mind. Sitting practice opens the door to observing this process of ‘selfing’, so it becomes a living reality and not just an idea. We do it all the time. And we can step outside the process, as a silent witness, and watch the show. And learn. And wake up.

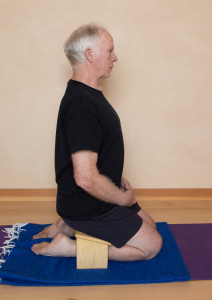

Practicing Stillness: The best and most universally acknowledged way to deeply open and stabilize ourselves in the Timeless is through sitting in silence. My first spiritual practice, from the book “Three Pillars of Zen” by Philip Kapleau, was ‘just sitting’, or shikantaza. Roshi Kapleau introduced me to Zen in a class I was taking at MIT in 1971 and I was inspired to give it a try. I hung with it for as long as possible, but it didn’t really take hold. It wasn’t until I came across the Iyengar style of yoga in 1978 that I developed a disciplined daily practice. There were so many fascinating things in the world of form to discover and explore that ‘just sitting’, with no agenda other than just ‘being’ was put on the back burner of my practice regimen. Now that I am ‘just sitting’ again every day, I have rediscovered how important this is and highly recommend that if you do not already have a sitting practice, jump in and get started.

Although sitting in silence is much more powerful in a group, tremendous insight can come from sitting on your own. Feel free to use a chair if need be, as there are no bonus points for sitting on the floor. If you do sit on the floor, use a cushion, bolster or something to lift your pelvis up off the floor and help keep your legs and hips from compressing. Space in the hips makes for much easier sitting. An uncomfortable body is a primary distraction. Any seated pose that works for you is fine.

Although sitting in silence is much more powerful in a group, tremendous insight can come from sitting on your own. Feel free to use a chair if need be, as there are no bonus points for sitting on the floor. If you do sit on the floor, use a cushion, bolster or something to lift your pelvis up off the floor and help keep your legs and hips from compressing. Space in the hips makes for much easier sitting. An uncomfortable body is a primary distraction. Any seated pose that works for you is fine.

Once the body is comfortable, then the mind needs to be addressed. The mind generates thoughts. That’s what it does and you cannot stop this. What you can do is give it something to do that is both focusing and relaxing and eventually the mind may learn to rest. This of course is to focus your attention on the breath.

In the Vibhuti Pada, (chapter 3) Patanjali describes samyama, the three fold process of bringing the attention to one place, keeping it there with discipline, and then staying there effortlessly, as dharana, dhyana and samadhi, and then acknowledges that you often have to start all over again as the attention will drift away. It’s a game or process. The intention is to sit with awareness, manage the moment as best possible, and be playful with your self. It is very easy to get frustrated when we realize just how restless the mind actually is. You can count the breaths, going to 10 and then starting over. Or, you can let each breath come and go, so every breath is ‘1’. Or you can recite a simple mantra over and over.

In sutras I-33 through I-39, Patanjali lists several other options for developing steadiness of mind. In I-33 Patanjali introduces ‘Loving Kindness’ meditation, known a maitri in Sanskrit, metta in Pali, where we begin to recognize Love and the primary expression of all that arises. One of my favorite sutras is I-39, where he says you can try anything that might work for you.

Just sit. Start with 10 minutes and work you way into longer sessions. You may begin to notice the background stillness, especially at the end of the exhalations, where the breath temporarily rests. As the body relaxes these pauses may get longer. You may also notice a pause between thoughts. As the mind relaxes, it still generates thoughts, just not as many, and they don’t crash into each other. Practice is really a form of impulse control, like you might teach a child. We don’t have to react to every thought or feeling that arises. We can just let them come and go, like clouds floating across the sky. We become an objective witness to them, and then even the witness drops away leaving awareness itself. Presence or Stillness is ‘ever present’, always. We just tend to not notice.

Embodying Impermanence Through Yin and Yang

Along with ‘resting in Stillness’, yoga students and somatic practitioners also explore the world of impermanence as Love, as it is expressed in creation, especially through the living body, in all of its dimensions and modes of expression. What does Love ‘feel’ like? We know, intuitively, but often forget. Freely moving qi can be a great reminder.

The Tao’sts of old were masters of exploring the inner realms of aliveness and Traditional Chinese Medicine, Qi Gong and Tai Qi and explicit examples of their discoveries. As mentioned above, the key principle is that all forms are composed of two fundamental qualities, Yin and Yang, which are different from, but not separate from each other. There is no Pure Yin or Pure Yang. Yin always contains some yang and yang always contains some yin. Refine either 10,000 times and still the same. They are “complementary opposites that combine, interact and mutually transform each other”.

Their relationship is cyclical and spiralic. As yin increases, yang decreases until a natural pause, like in the breathing, arises and the cycle reverses, with yin decreasing as yang increases until it reaches its maximum. Another pause, and the cycle shifts again. Because of time and the dynamic nature of reality, every cycle is unique. As westerners, raised in a strongly dualistic, Judeo-Christian-Islamic world, where there is right and wrong or God and the devil, the inseparable nature of yin and yang is challenging at first. We want tangible stable ‘truths’ to hold onto, but they can never be found by holding on to anything. But we can find stability by ‘letting go’ and noticing how the universe flows along quite effortlessly without our intervention. Then we allow our selves to flow with the Universe, the Tao, practicing ‘wu wei’ effortless effort, or doing by non-doing. This is “Ishvara Pranidhana of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras.

Some Clues to explore Yin and Yang

Yin: water, earth, down, body, blood, emotions, storing, restoring, resting, yielding, receiving, cooling, condensing, centripetal force, introversion/introspection, endoderm, gut body, front body,

Yang: fire, heaven/sky, up, qi, thoughts, using, acting, moving, initiating, heating, expanding, centrifugal force, extroversion, ectoderm, nerves/skin/back body

From Sitting to Standing and the Principle of ‘Pre-Movements’

Sitting is fundamentally yin. It is a ‘grounded’ pose, root chakra planted on the earth, designed to ‘not move’ the physical body, but to help it find stillness. But there is also ‘yang’. The embodied state always has the non-stop movements of circulation, breathing, peristalsis, and muscle tone, but when there is balance, the gross body can sustain a level of stillness that frees the mind to further let go. Yin grounds the body in Mother Earth, and a subtle yang keeps you upright and awake. Not enough yang (or too much yin) and your pose collapses or your mind becomes dull and sleepy. Not enough yin (or too much yang) and the body/mind becomes fidgety and restless.

When transitioning from sitting to standing, a predominantly moving pose, we are shifting from a yin dominant to a yang dominant position and smooth transitions are important for  safety as well as staying fluid (sattvic) and light. This is when being able to feel the ‘pre-movement is essential. If I am still and have an intention to move, my body will, usually totally unconsciously, prepare some stabilizing action so that my movements don’t knock me off balance. This is the ‘pre-movement’. If I observe this carefully, I may notice the pre-movement is often a muscular contraction somewhere, a grasping or grabbing on to brace the body. We want to change this pattern by using the flow of qi between yin and yang for all of our pre-movements.

safety as well as staying fluid (sattvic) and light. This is when being able to feel the ‘pre-movement is essential. If I am still and have an intention to move, my body will, usually totally unconsciously, prepare some stabilizing action so that my movements don’t knock me off balance. This is the ‘pre-movement’. If I observe this carefully, I may notice the pre-movement is often a muscular contraction somewhere, a grasping or grabbing on to brace the body. We want to change this pattern by using the flow of qi between yin and yang for all of our pre-movements.

When you are ready to transition from sitting to standing, first feel the yang/uplifting energy already waiting to grow further and allow it to extend it out through your legs to open the knees, ankles and hips. The joints need the space of yang. Awaken the arms in a similar manner and then feel the weight of the pelvis and root of the body. As the weight yields (yin) into the floor, let the responding yang begin to rotate the body, right or left,and then lean over to place the hands on the floor as if you are ready to crawl. There is continuous flow. This is actually the first moving pose after sitting. Grow your hands down into the floor with your hands as the next pre-movement to spiral again to one knee and then finally to standing. Notice the relationship to pushing down and rising up. This is the spiral dance of yin and yang. The Pre-movements are the yielding yin, connecting to gravity as the stabilizing action which leads to an effortless yang movement.

Standing is the beginning of the dominant form of human movement, walking or running. This is easily forgotten in ‘tadasana’ when the tendency is to ‘hold’ the body in place. It is certainly possible to stand in ‘stillness’, as the military often demands, but this is not the body’s first choice from this pose. Sitting is down, grounded and yin, where as standing is up, rising, expanding, moving into the world. However, standing absolutely requires the grounding yin support. Think of this as a continuous pre-movement. You feel this in surfing and skiing, where the body is ‘relatively’ upright, but the yielding to the gravitational glue provides the stability and there is no collapse or unnecessary contraction. (Healthy muscle tone is not contraction, as I use the term. It is vibrant and dynamic. contraction is blocking the flow of qi.)

Yin/yang of Standing

In tadasana, notice the up energy (yang) extends up to the heavens and then re-discover your weight as down/yin and let your ankles, knees and hips yield to gravity by flexing slightly. Yin is flexion, yang is extension. Imagine you are on skis or s surf board, so as you relax down, there is a corresponding release up into slight extension. Let the flexing/extending dance continue as if you are riding a very subtle wave. It is like floating. Notice if you hang out on one side more than the other. Most of us do. Is the down/yin blocked, or is it the up/yang, or both? Because of the uniqueness of the human upright posture, far more yang than other creatures, most of us have lost a lot of grounding/yin. This results in tension in the feet, strain through the knees and a lot of tightness in the hips and lower back. (And most of the rest of the body as well!) All signs of faulty pre-movements.

Walking Meditation as Yoga Practice

To release the yin down, we have to learn how to walk all over again, one step at a time. When the yin is blocked, we lift our leg, drag it forward and then land on it again further compressing or straining the tissue. In the image to the right, I have exaggerated the first step, but the principle is to put the weight on one foot and release down slightly, yielding to the K-1 point (kidneys are the ‘yinnest’ of the organs, governing the movement of water in the body) yin and mother earth. I place the left heel on the floor in front of me before I shift my weight, still yielding (yin).

To release the yin down, we have to learn how to walk all over again, one step at a time. When the yin is blocked, we lift our leg, drag it forward and then land on it again further compressing or straining the tissue. In the image to the right, I have exaggerated the first step, but the principle is to put the weight on one foot and release down slightly, yielding to the K-1 point (kidneys are the ‘yinnest’ of the organs, governing the movement of water in the body) yin and mother earth. I place the left heel on the floor in front of me before I shift my weight, still yielding (yin).

The weight shift (yang) comes by pressing down and back through K-1, lifting the heel, while simultaneously rolling onto K-1 of the left foot. Remain vertical, gliding forward without leaning forward. (That becomes running.) Back to ‘yin’. With the next step the left foot yields to the weight, right foot lifts effortlessly and heel descends and the cycle repeats.

This “Yield and Push”, pre-movement and action, is a fundamental movement pattern and if you can slow down and really feel the smooth transitions, the whole body softens and opens.

Tadasana is really a ‘yang’ pose for movement, and the standing poses that follow are all  poses that enhance and liberate pour capacity to move. If we feel yin as grounding, we can use our work imagining tails as deeper yin. I moving from tadasana to uttanasana, I first feel grounded through root chakra, pelvis, legs and feet (yin/yielding. I then engage the tail to extend back and through the pelvis, without losing the grounding through the legs. This opening and deepening of the ‘yielding to earth’ yin

poses that enhance and liberate pour capacity to move. If we feel yin as grounding, we can use our work imagining tails as deeper yin. I moving from tadasana to uttanasana, I first feel grounded through root chakra, pelvis, legs and feet (yin/yielding. I then engage the tail to extend back and through the pelvis, without losing the grounding through the legs. This opening and deepening of the ‘yielding to earth’ yin  is a reflex known as anal rooting, as seen in the baby to the right. The easiest way to feel this is in a chair forward bend.

is a reflex known as anal rooting, as seen in the baby to the right. The easiest way to feel this is in a chair forward bend.

We take the same action and move back and up (a little yang) to come into uttanasana, the standing forward bend. No need the straighten the legs too quickly. Extension (yang) has to flow from the release of flexion (yin). Keep the spine soft and let the hips and knees extending slowly, when ready. No force, no effort. In a forward bend, the yang back body yields or releases, but the yin front has to expand to receive this. Most students collapse the front and the pose stalls in conflict. Keep the core lengthening to allow the back to release more and more.

We can use the microcosmic orbit to help us feel this process. The back body/yang and the front body/yin combine in a circle, crown chakra on top (yang), root chakra on the bottom (yin). Tadasana is a neutral pose for the core, neither flexed/yin, or extended/yang. In either a forward bend or backbend the circle of energy should remain flowing, even as the gross body structures are challenged. In uttanasa, the back opens and yields as the front condenses without contracting. In a backbend, the front opens and yields as the back body condenses, without contracting. Feel this to know the limits of your body. The role of practice is to restore balance and increase vitality, not to aggressively force openings.

the front body/yin combine in a circle, crown chakra on top (yang), root chakra on the bottom (yin). Tadasana is a neutral pose for the core, neither flexed/yin, or extended/yang. In either a forward bend or backbend the circle of energy should remain flowing, even as the gross body structures are challenged. In uttanasa, the back opens and yields as the front condenses without contracting. In a backbend, the front opens and yields as the back body condenses, without contracting. Feel this to know the limits of your body. The role of practice is to restore balance and increase vitality, not to aggressively force openings.

A similar process is involved in moving into triangle pose. The yang action of moving into the pose engages the yin/tail/pelvis to elongate away from the head. The body flows into the pose because the root is lengthening, through the front hip socket, tail and inner back leg.

A similar process is involved in moving into triangle pose. The yang action of moving into the pose engages the yin/tail/pelvis to elongate away from the head. The body flows into the pose because the root is lengthening, through the front hip socket, tail and inner back leg.

In these ‘lateral space creating’ poses such as tikonasana, parsvakonasana, ardha chandrasana, and anantasana we can also visualize rotating our micro-cosmic orbit into the lateral plane to feel our wings

In these ‘lateral space creating’ poses such as tikonasana, parsvakonasana, ardha chandrasana, and anantasana we can also visualize rotating our micro-cosmic orbit into the lateral plane to feel our wings opening like a bird in flight. This action creates space in the center channel, as right and left sides expand away.

opening like a bird in flight. This action creates space in the center channel, as right and left sides expand away.

Side Body Interlude: Blood Breathing

This breathing exploration can be done in any comfortable position, sitting or lying supported. I also play with it while doing my swimming meditation. The premise is to imagine the expanding chest cavity is drawing blood into the lungs from the rest of the body, but especially the lower body, below the diaphragm. We know that inhalation draws air into the lungs, but the vaccuum created by expanding the chest volume also helps in circulation. On the inhale, expand the chest slowly and gradually and feel the blood coming from your feet up your core, through your heart and into the lungs. On the slow even exhalation, visualize the blood flowing through the heart and out into the body. Rest between cycles. As the lungs expand sideways, away from the heart, like the branches and leaves of a large oak tree, feel the lateral space and the quiet sensation of the head. Over time allow the expanded chest to stay open during the exhalation as the lungs and diaphragm take care of the out breath.

The Yin/Yang of twisting: Twisting poses rotate around the core axis, an action that helps define human movement. We love spiralic movments and twisting, whether in dance, throwing a frisbee, of swing a bat, golf club or tennis raquet, power is generated in twisting. See it as a coiling (yin) to store  energy, and then uncoiling to release the energy (yang). As there are many joints, the movement has to be fluid and sequencial. In this photo, there is abalance of yin and yang which leaves me in a dynamically stable pose. The hoop helps me to keep right and left sides working together. Otherwise, one side will race ahead,leading to a breakdown in the flow of qi. If I were to mimic the throwing of a frisbee, I would trace the yin grounding through K-1, creating a rebounding yang lift spiraling up through legs, hips, spine, ribs, shoulders and flowing out through my throwing hand, at each step on the way the coiled flexors releasing into extension until the frisbee leaves my fingertips.

energy, and then uncoiling to release the energy (yang). As there are many joints, the movement has to be fluid and sequencial. In this photo, there is abalance of yin and yang which leaves me in a dynamically stable pose. The hoop helps me to keep right and left sides working together. Otherwise, one side will race ahead,leading to a breakdown in the flow of qi. If I were to mimic the throwing of a frisbee, I would trace the yin grounding through K-1, creating a rebounding yang lift spiraling up through legs, hips, spine, ribs, shoulders and flowing out through my throwing hand, at each step on the way the coiled flexors releasing into extension until the frisbee leaves my fingertips.

From lying to standing: the awakening of movement in babies as a spiral

1.Lying down: very yin. Play here as happy baby/seaweed pose. 2. Using your fluid body only, no limbs, roll over to the reptile pose. Early yang. Use can move about form here, using limbs. Feel the spiral that gets you here. 3. Loading the arms, feel the floor and push to sitting. Another spiral to a yin pose. 4. Reverse the spiral direction to come to the yang crawling position. 5. another reverse spiral to come to this intermediary yin pose. Helpful if you need a chair or desk to help you up to the next step. 6. Load the front leg and push up to walking yang. Youv’e made it! ready to explore the world. 7. Reestablish ground, coming back to tadasana, where yin and yang can rest in balance, until you are ready to move again.

Microcosmic orbit in hip opening poses;

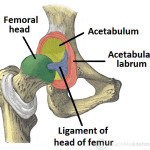

If we understand the double action of the microcosmic orbit, that is, sending energy in both directions at the same time to open root and crown chakras, we can apply that same principle to challenging hip issues. To truly open the hips, energetically speaking, both directions must be clear. In other words, the femur and pelvis need to move in opposite directions, and when the physicl movement stops, the energetic one has to keep going or else the qi stops. Many students hit a wall in their poses because they do not keep the qi moving when they are at their edge. Slow down, as you near you edge, feel space

If we understand the double action of the microcosmic orbit, that is, sending energy in both directions at the same time to open root and crown chakras, we can apply that same principle to challenging hip issues. To truly open the hips, energetically speaking, both directions must be clear. In other words, the femur and pelvis need to move in opposite directions, and when the physicl movement stops, the energetic one has to keep going or else the qi stops. Many students hit a wall in their poses because they do not keep the qi moving when they are at their edge. Slow down, as you near you edge, feel space  between the bones and the two energies pass through the joint. In the chair forward bend, the pelvis has to lift (yang) and the femurs drop (yin) to sustain space for the qi. If they both lift or both drop, you get stuck. If the chair inhibits the dropping, lift up a tiny bit off the chair and then sit by dropping the femurs onto the chair, not the sitting bones.

between the bones and the two energies pass through the joint. In the chair forward bend, the pelvis has to lift (yang) and the femurs drop (yin) to sustain space for the qi. If they both lift or both drop, you get stuck. If the chair inhibits the dropping, lift up a tiny bit off the chair and then sit by dropping the femurs onto the chair, not the sitting bones. Then extend the dropped femurs out through the heels, lift the pelvis up, and elongate through the body to go deeper.

Then extend the dropped femurs out through the heels, lift the pelvis up, and elongate through the body to go deeper.