Theme of Weekend 3 : What is Mind? (part 1)

Meditation: Heart Field followed by Hub of Awareness (see previous post).

Continuing to rest in non-dual emptiness (aka being, presence, Purusha, atman)

at the ‘hub’, while allowing the world to unfold. No need to repress or push the world away.

Pranayama Practice: Sama Vrtti and differentiating ribs, spine and diaphragm.

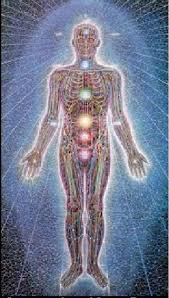

Asana Practice: Continue refining what we have learned in the first two sessions. From the meditation, tracking energy flow from heart to feet/earth and back, integrating into arms and skull, through crown chakra to the heavens, and back to the heart. More work with standing poses, dogs, and beginning to explore inversions, backbends, restoratives. How do yoga postures affect ‘mind states? How does our approach, our belief systems about the body, about practice, affect mind states? How are emotional energies affected?

Mantra/Chanting: Learn: 1. Invocation to Patanjali: 2. Om namste astu bhagavan…

3. Om saha navavatu… and 4. Purnamadah, purnamidam… (See below.)

Yoga Sutras: Questions arising from study group:

Question 1: Please comment on the use of mantras in one’s practice, especially ‘Om’. Are there any secrets to be found in the chanting of mantras? Maybe not secrets, just how does this work? How does this help our practice?

Answer: there are many layers to working with mantras, whether recited out loud, or silently in a practice known as japa. The most obvious is that the mantra provides a seed to focus the mind. This brings stability. When repeated over and over, the possibility of the mind dissolving into emptiness arises as the need to anticipate what might come next disappears. The aspect of mind known as manas (see below) continues the chanting and the buddhi can rest in silence. Another aspect is that each of the Sanskrit sounds have a specific vibration that affects the whole organism. The way the vowels and consonants are ordered creates waves of sound that bring coherence. Different mantras have different wave patterns. Om is the simplest and most powerful as it creates a very simple coherent circular or spherical vibration. The best way to explore is to try chanting in your practice. It will help keep you breathing, if nothing else!

Answer: there are many layers to working with mantras, whether recited out loud, or silently in a practice known as japa. The most obvious is that the mantra provides a seed to focus the mind. This brings stability. When repeated over and over, the possibility of the mind dissolving into emptiness arises as the need to anticipate what might come next disappears. The aspect of mind known as manas (see below) continues the chanting and the buddhi can rest in silence. Another aspect is that each of the Sanskrit sounds have a specific vibration that affects the whole organism. The way the vowels and consonants are ordered creates waves of sound that bring coherence. Different mantras have different wave patterns. Om is the simplest and most powerful as it creates a very simple coherent circular or spherical vibration. The best way to explore is to try chanting in your practice. It will help keep you breathing, if nothing else!

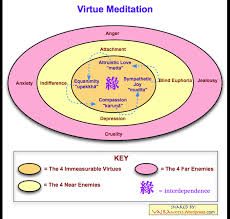

Question 2: Please comment on ways to clarify the mind as mentioned in Sutras I-33 to I-39. Answer: Big question! Patanjali is very open minded about finding what works. Sutra  1-33 is worth a book in itself, but recognizes that negative emotional patterns and habits reek havoc on the quietness of the mind and suggests four practices, the Brahma Viharas, which are also an important part of Buddhist teaching. I-34 uses the stillness at the end of exhalation, possibly cultivated through pranayama. As the breath becomes more effortless, through asana as an example, the mind settles naturally. When the breath is still, the mind is quiet. The rest of these sutras are a bit esoteric, except for the last, where Patanjali says that anything that works for you can be an object of meditation.

1-33 is worth a book in itself, but recognizes that negative emotional patterns and habits reek havoc on the quietness of the mind and suggests four practices, the Brahma Viharas, which are also an important part of Buddhist teaching. I-34 uses the stillness at the end of exhalation, possibly cultivated through pranayama. As the breath becomes more effortless, through asana as an example, the mind settles naturally. When the breath is still, the mind is quiet. The rest of these sutras are a bit esoteric, except for the last, where Patanjali says that anything that works for you can be an object of meditation.

Question 3: How do we relate ways to clarify the mind to the three gunas (sattva, rajas, and tamas)? A rajasic mind needs to quiet down. Longer exhalations and restorative poses are some ways to help. A dull mind needs activation, exercise, fresh air, backbends, movement to help bring the energy up. A sattvic mind is already there. Enjoy.

Main Theme: What do we mean by ‘mind’?

This a complex question that will be unfolded over three seperate weekends in the course, using Patanjali and other traditional perspectives as well as modern neuro-scientific understandings. In this introduction, we will look at the overall sense of mind and mind activity. In later weekends we will go into emotions and some cutting edge neuroscience. As we are working with Patanjali, it will be helpful to see how he looks at mind. Then we will compare that with Dan Siegel’s interpersonal neurobiology.

Samkhya, the philosophical foundation of the Yoga Sutras, describes mind, known in general as citta, as involving three distinct but interwoven processes.

The first process, known as manas (YS 1-35, II – 53, III-48), organizes sensory information, records and stores memory and allows for ‘auto-pilot’ actions. It is the bookkeeper, filer and office manager of the citta.

The ahamkara, literally the “I” maker, builds a self sense out of experiences and includes  likes and dislikes, tendencies and habits. Although there is no direct mention of the ahamkara in Patanjali, it is implied in sutra I-4, vrtti sarupyam itaratra. Here Patanjali describes the general state of confusing the transient movements of mind, in other words, the functioning of the mind, with the immutable Purusha, the True Self in Samkhya. The ahamkara, sometimes called the ego in Western psychology, is an absolutely necessary aspect of a healthy mind. It is not the true nature of ‘I”, but can easily convince itself otherwise. We will develop this very important idea of “Self” later in the course.

likes and dislikes, tendencies and habits. Although there is no direct mention of the ahamkara in Patanjali, it is implied in sutra I-4, vrtti sarupyam itaratra. Here Patanjali describes the general state of confusing the transient movements of mind, in other words, the functioning of the mind, with the immutable Purusha, the True Self in Samkhya. The ahamkara, sometimes called the ego in Western psychology, is an absolutely necessary aspect of a healthy mind. It is not the true nature of ‘I”, but can easily convince itself otherwise. We will develop this very important idea of “Self” later in the course.

The buddhi is the intelligence. This is cultivated in “mindfulness practice” and refers to awareness of what is arising in the present moment, analysis, and on going choice of action. This is in contrast with the manas, where decisions are made sub-consciously from habit and routine. In integration, buddhi and manas can work together skillfully, with the sub-routines operating in the background while modifications are made moment to moment. Reading is an example. As you read these words, you have previously learned a language with vocabulary and grammar and this foundation allows the intelligence to contemplate the meaning, looking for nuances and implications from the writer.

The word vrtti, mind activity, refers to the energetic nature of mind. Mind is not a noun, it is a verb. Mind is dynamic activity. The Self, or Purusha in the Sutras, is not the mind. According to Patanjali, mind activity, aka, energy/information flow, can come in three possible flavors: too much, too little, and just right, like the Goldilocks story. The Sanskrit term guna refers to energy in general, but here we will use it to examine mental energy. The first guna is rajas or the adjective form, rajasic, refers to action or movement; inertia of motion is name offered by Sir Isaac Newton. When out of balance, i.e., too much rajas, these energies will be in the form of chaos or aggresssiveness, and the mind field is disruptive and unstable. Tamas, or tamasic, refers to the opposite of movement, inertia of rest. When out of balance the stability of tamas degenerates into stagnation. Here the mind activity is sluggish or stupified.

In Sattva or sattvic states, mind activity is harmonious with a perfect, dynamic balance between movement and stability. This is an excellent definition of mental health, also known as integration. Dan Siegel, the acronym man, uses the word FACES to highlite the qualities demonstrated in an healthy integrated system, like the human nervous system. It is Flexible, Adaptable, Coherent, Energized and Stable. Just about every neuro-psychological disorder falls into one of two categories where the process on neural integration is disrupted: disorders of chaos (excess rajas) or rigidity (excess tamas).

In your practice, observe these aspects of mind activity. Learn to recognize them in action. Emotional self regulation is the key to mental health and the beginning of yoga. We could spend years exploring the dimensions of mental health, but this is a tiny beginning.

Dan Siegel, author of ‘The Developing Mind” and many other mind-based books, defines the mind as “an embodied and relational process that organizes the flow of energy and information.” “Embodied” recognizes the there is no mind-body split, although this split is often implied in modern psychological language. “Relational’ recognizes that we are embedded in relationships and mind does not exist in isolation, although the mind can often convince itself that this is so. The body is energy. Information is a highly complex form of energy and the self-organizing aspects of mind uses information to bring further levels of integration to maintain health and well being. Yoga taps into this process and develops and refines it further and further.

Dan Siegel, author of ‘The Developing Mind” and many other mind-based books, defines the mind as “an embodied and relational process that organizes the flow of energy and information.” “Embodied” recognizes the there is no mind-body split, although this split is often implied in modern psychological language. “Relational’ recognizes that we are embedded in relationships and mind does not exist in isolation, although the mind can often convince itself that this is so. The body is energy. Information is a highly complex form of energy and the self-organizing aspects of mind uses information to bring further levels of integration to maintain health and well being. Yoga taps into this process and develops and refines it further and further.

One of the most important types of mind activity is integration, described by Dan as ” the collaborative, linking functions that coordinate various levels of processes within the mind and between people.” (DM pg 301) It can also be described as the linking of differentiated systems to create something larger than the sum of the parts. Hand – eye coordination is an example of integration. The visual system and the kinesthetic system work together to allow a complex motor skill such as hitting or catching a baseball. These are sattvic mind states.

Reading is another example of integration. The retina registers light and dark patterns, the pattern recognition portion of the brain interprets the information into words, and the meaning making aspect draws conclusions, makes connections, inferences, etc. Now, If you can read Thai, you will understand that การให้ทานความรู้เป็นทานอันประเสริฐสุด says ‘Passing on knowledge is the greatest gift.” If you do not read the Thai script not, the forms do not convey any information.

The term samadhi, the primary practice of used in the Yoga Sutras, describes a state of relaxed focused attention directed onto the process of attention. Conscious attention is integrating, whether as mindful attending to the present, focal attention known as samadhi, or insight where attention rests in itself. These involve using a sustained sattvic flow of energy/information to develop and strengthen deeper and deeper states of integration. Yoga studies the process of attention and integration and refines this over and over again.

In “Mindsight” Dan Siegel defines eight domains of integration,

(and I add 1, dorsal/ventral). The first and most basic is:

Integration of Consciousness, which essentially is the definition of yoga. This refers to building skills to stabilize attention and then working with the global awareness of all aspects of our lives to help bring them into a state of harmony. Perceptions, bodily sensations, emotions, actions, relationships and our own thoughts are examined. The “Hub of Awareness” meditation is the key practice.

Next come the three ‘spatial’ domains, highly relevant to the somanauts/yoga students.

Horizontal Integration helps to link right and left brain activities. The right develops early on and involves spatial awareness, imagination, non-verbal communication, holistic thinking and more. The left brain develops later and is responsible for logic, linearity, literal thinking, written and spoken language and more. Read ” A Stroke of Insight” by Jill Bolt Taylor for a fascinating unfolding of some right brain/left brain skills and perspectives. If the linking between these hemispheres is blocked, the richness and complexity of life can be lost. Yoga poses and other forms of mindful movement help integrate right and left sides of the brain.

Vertical Integration refers to the vertical nature of the nervous system with nerves form the lower body ascending up through the spinal cord into the brain stem, the limbic structures and the cortex. People who ‘live in their heads’ are lacking in vertical integration. Hatha yoga brings the awareness and intelligence of the cells, organs, muscles and bones into conscious awareness and is thus a major practice of vertical integration.

Depth or Dorsal/Ventral Integration refers to the third and most challenging of the spatial directions, front to back. Most of us have very little perception of depth in the body. Head/tail and right/left are relatively easy, but we are pretty shallow from front to back. This becomes important as we dive into embryology and discover the tubular nature of structures. Without dorsal/ventral integration, we have no middle, no center. we are two dimensional. Breathing begins the process of discovering the inside that differentiates front from back. When e find the ‘expansion fields, we can take that feeling anywhere.

The next three involve temporal domains, where aspects past, present and future are integrated.

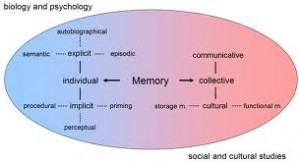

Memory Integration involves linking two basic types of memory. Implicit memory begins at conception if not before and encodes all the experiences the cell, enmbryo, fetus, baby encounters. These memories shape our behavior and relationships from way in the background. Explicit memory includes autobiographical memory, the sense that ‘I remember’ and often doesn’t arise until the second year of life. In a healthy individual the implicit encodings and our ‘remembering work together to help us stay in the present moment with awareness and sensitivity. Trauma can impair memory integration. PTSD, post traumatic stress disorder blocks the implicit experience of the trauma to become part of explicit memory. Thus a war veteran can hear a firecracker explode and instantaneously be thrown into the war zone, which is experienced as happening now.

Memory Integration involves linking two basic types of memory. Implicit memory begins at conception if not before and encodes all the experiences the cell, enmbryo, fetus, baby encounters. These memories shape our behavior and relationships from way in the background. Explicit memory includes autobiographical memory, the sense that ‘I remember’ and often doesn’t arise until the second year of life. In a healthy individual the implicit encodings and our ‘remembering work together to help us stay in the present moment with awareness and sensitivity. Trauma can impair memory integration. PTSD, post traumatic stress disorder blocks the implicit experience of the trauma to become part of explicit memory. Thus a war veteran can hear a firecracker explode and instantaneously be thrown into the war zone, which is experienced as happening now.

Narrative Integration is bringing coherence to the telling of our own story. Interestingly, the narrative function resides in the left hemishere and the autobiographical memory in the left. The more we can use story to make sense of our experiences and our actions, especially those of our childhood, and bring coherence to our life stories, the better parents we will be.

Temporal Integration brings in the capacity of the pre-frontal cortex to anticipate the future and even the deaths of ourselves and loved ones. This can induce more than a fair amount of anxiety so mindfulness practice can bring some ease and relaxation around ‘not knowing’ and help us be more comfortable with uncertainty. Emptiness meditation also brings insight into the nature of birth and death.

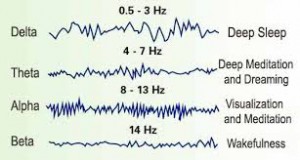

State integration allows us to acknowledge the different ‘mind states’ we naturally go through during the cpurse of a day. A ‘mind state” is  “the total pattern of activations in the brain at a particular moment in time.” DM pg 208. We can all recognize the difference between the states of deep sleep, dream sleep and waking. And during waking, we can be alert, agitated, meditative, relaxed etc. Each of these involves a pattern of brain activity which can often be demonstrated through the electrical patterns known as brain waves. Sometimes we can generate conflicting states or ones we find to be ‘unpleasant’. Rather than rejecting or trying to deny their existence, we see their presence and look more mindfully at their expressions, giving permission to have these states. Spiritual bypassing is an attempt to ignore, deny or avoid states that do not meet our ‘spiritual standards’. This is a very unhealthy approach. Compassion and spacious understanding are healing.

“the total pattern of activations in the brain at a particular moment in time.” DM pg 208. We can all recognize the difference between the states of deep sleep, dream sleep and waking. And during waking, we can be alert, agitated, meditative, relaxed etc. Each of these involves a pattern of brain activity which can often be demonstrated through the electrical patterns known as brain waves. Sometimes we can generate conflicting states or ones we find to be ‘unpleasant’. Rather than rejecting or trying to deny their existence, we see their presence and look more mindfully at their expressions, giving permission to have these states. Spiritual bypassing is an attempt to ignore, deny or avoid states that do not meet our ‘spiritual standards’. This is a very unhealthy approach. Compassion and spacious understanding are healing.

Interpersonal Integration recognizes that we are all ‘interbeing’ to use Thich Nhat Hahn’s term. We all are dependent upon others for comfort, survival, recognition, fun and more. Our brains have evolved to align with other brains, our minds with other minds, to create mind states of two and more beings entwined and attuned. This helps us stay grounded in the world. We learn to come together and separate. Sometimes those separations are smooth, sometimes they are ruptures, leaving psychic wounds. Learning how to repair these ruptures is crucial to all relationships.

om saha na vavatu

namaste astu

patanjali invocation