Stillness

(Notes from the Detroit workshop, Jan 2013)

Mobility and motility are both expressions of the world of form. Buddhists call this impermanence, Patanjali uses the term prakriti, and the fundamental principle is change. Life is constant change. The body is a verb, not a noun. Movement is the basic nature of the body, not something the body does. Much of the beginning work in yoga is to help release the energy blockages arises from confusion, trauma and injury.  Then life flows more freely, more coherently and the emotions begin to settle. Then, you are ready for the yoga of Patanjali. As he says in the first three sutras: I-1 atha yoganushasanam. I-2, yogash citta vrtti nirodhah; I-3, tada drashtuh svarupe avasthanam. Now begins the study of yoga. Yoga is the reigning in of the reactivity of the mind. Then there is abiding, with stability, in stillness.

Then life flows more freely, more coherently and the emotions begin to settle. Then, you are ready for the yoga of Patanjali. As he says in the first three sutras: I-1 atha yoganushasanam. I-2, yogash citta vrtti nirodhah; I-3, tada drashtuh svarupe avasthanam. Now begins the study of yoga. Yoga is the reigning in of the reactivity of the mind. Then there is abiding, with stability, in stillness.

Stillness is a word that points to the unchanging timeless primordial being that underlies all forms. In this way, stillness is not the absence of movement, but the unbounded infinite spaciousness in which movements come and go. This is analagous to saying the eternal present moment, ‘Now’ is not the absence of time but the source of all of time, past, present and future. Awareness is another word that is used. Awareness is contrasted to ‘what arises in awareness. Viveka, a lovely Sanskrit work from the Yoga Sutras means to know the difference between what is subject to change (prakriti, what arises in awareness) and the unchanging (purusha, Awareness). To recognize and truly know that stillness is the Truth of I, of Self, not the mind/body/personality that is always undergoing changes, is enlightenment, liberation. Awakening is the process of recognizing, deepening and stabilizing this realization as you go about your daily life activities.

Adyashanti, my mentor in awakening, contrasts what he calls ‘True Meditation’ with meditative practices where the intention is to develop concentration or some other mind state. He describes True Meditation the way Patanjali defines yoga; “it is most fundamentally an attitude of being—resting in and as being. Once you get the feel of it, you will be able to tune into it more and more often during your daily life. Eventually, in the state of liberation, meditation will simply become your natural condition.”

Adyashanti, my mentor in awakening, contrasts what he calls ‘True Meditation’ with meditative practices where the intention is to develop concentration or some other mind state. He describes True Meditation the way Patanjali defines yoga; “it is most fundamentally an attitude of being—resting in and as being. Once you get the feel of it, you will be able to tune into it more and more often during your daily life. Eventually, in the state of liberation, meditation will simply become your natural condition.”

“True Meditation has no direction or goal. It is pure wordless surrender, pure silent prayer. All methods aiming at achieving a certain state of mind are limited, impermanent and conditioned. Fascination with states leads only to bondage and dependency. True Meditation is effortless stillness, abidance as primordial being.” Or as Patanjali states in I-3, tada drashtuh svarupe avasthanam, then the Seer abides in her own True Nature.

“In True Meditation all objects (thoughts, feelings, emotions, memories, etc)” (what Patanjali calls ‘vrttis’), are left to their natural functioning. This means that no effort should be made to focus on, manipulate, control, or suppress any object of awareness.” (This is not so easy!) “In True Meditation, the emphasis is on being awareness—not on being aware of objects, but resting as conscious being itself. In meditation, you are not trying to change your experience; you are changing your relationship to your experience.” …”An attitude of open receptivity, free of any goal or anticiption, will facilitate the presence of silence and stillness to be revealed as your natural condition.”

These quotes come from Adyashanti’s “The Way of Liberation: A Practical Guide to Spiritual Enlightenment”. Soft cover (54 pages) book and a free downloadable copy available at http://www.adyashanti.org/index.php?file=productdetail&iprod_id=533.

Spiritual Enlightenment”. Soft cover (54 pages) book and a free downloadable copy available at http://www.adyashanti.org/index.php?file=productdetail&iprod_id=533.

See also ‘Stillness Speaks’ by Eckhart Tolle for another eloquent perspective on ‘stillness’.

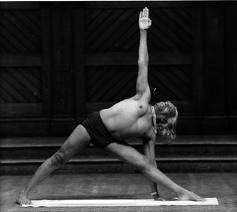

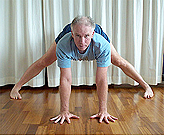

Photo credits: Sean Kilmurray, www.seankilmurrayphotography.com