Lesson 14: Samyama in Asana

We now take a much deeper look at the meditative side of asana. This is not physical exercise, stretching or gymnastics of the modern yoga scene, but asana as yoga, an internal movement into the heart and soul of being alive as described by B.K.S. Iyengar.

Summer of 1984 saw two major conventions happening in San Francisco. The Democrats were first, in July,  nominating Walter Mondale and Geraldine Ferraro for the ticket to run against Ronnie Reagan and George Bush the elder. Ferraro was the first female ever nominated for either President or Vice President, but, unfortunately it was a Republican world in those days and the Dems had no chance.

nominating Walter Mondale and Geraldine Ferraro for the ticket to run against Ronnie Reagan and George Bush the elder. Ferraro was the first female ever nominated for either President or Vice President, but, unfortunately it was a Republican world in those days and the Dems had no chance.

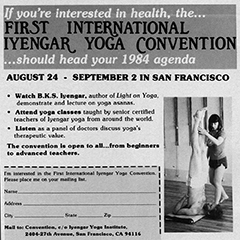

Later that summer, the world wide Iyengar community descended upon the Bay Area for the first (and only!) International Iyengar Yoga Convention. (Check out the hairy guy with Judith Lasater in the flyer!) During one of the question and answer sessions at the convention, Ramanand Patel asked B.K.S. Iyengar “What is ‘samyama in asana?”  As asana is the main focus of the Iyengar system, Ramanand’s question was designed to link posture with the meditative depths of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras. We recorded the sessions on those old fashioned audio cassettes and I transcribed Iyengar’s answer word for word. Carol Cavanaugh and I edited it for punctuation and clarity and we published it as the lead article in the Iyengar Yoga Institute Review in October 1985.

As asana is the main focus of the Iyengar system, Ramanand’s question was designed to link posture with the meditative depths of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras. We recorded the sessions on those old fashioned audio cassettes and I transcribed Iyengar’s answer word for word. Carol Cavanaugh and I edited it for punctuation and clarity and we published it as the lead article in the Iyengar Yoga Institute Review in October 1985.

I wish I could include the audio but I cannot find it. I listened to this so many times back in the 80′s his voice has burned into my brain cells. Even as I write this I hear his animated voice. After over thirty years of my own inquiry into this process, I find his words continue to ring with amazing genius and depth. Words are not his strength, but he was inspired that day. As you read the transcript, recognize that the words were being spoken to an audience. This first part will include the article in full, as it first appeared in 1985 and I have also added some photos and charts that were not part of the original publication. In part two, I will integrate my own commentary from the perspectives of neuro-science and my personal practice.

****************

Note: the following is a transcript of a discourse given by B.K.S. Iyengar  at the First International Iyengar Yoga Convention in August, 1984. Unfortunately, Mr. Iyengar’s first sentence or two were not recorded and the text begins in mid sentence. However, his ensuing discussion strongly implies that the missing segment introduces the five gross elements: fire, air, earth, water and ether. These elements compose part of the 25 principles of the Samkhya model of reality. Samkhya is the philosophical foundation of yoga. (See accompanying chart.)

at the First International Iyengar Yoga Convention in August, 1984. Unfortunately, Mr. Iyengar’s first sentence or two were not recorded and the text begins in mid sentence. However, his ensuing discussion strongly implies that the missing segment introduces the five gross elements: fire, air, earth, water and ether. These elements compose part of the 25 principles of the Samkhya model of reality. Samkhya is the philosophical foundation of yoga. (See accompanying chart.)

In this model, the evolution of consciousness proceeds from the most subtle aspects of mind to the grossest aspects of matter. Mr Iyengar describes the use of asana to retrace this process from the gross level back to pure consciousness. This requires the integration, the uniting of all the diverse aspects and elements into a single harmonious flowing consciousness.  The yogic term for this integrative process is Samyama. Samyama is the simultaneous practice of Dharana, Dhyana, and Samadhi, the last three limbs of Patanjali’s eight limbs of yoga and is described and discussed in Chapter Three of the Yoga Sutras. Kofi Busia’s succinct translation of the first few sutras of this chapter may be of use to the reader who is unfamiliar with these terms.

The yogic term for this integrative process is Samyama. Samyama is the simultaneous practice of Dharana, Dhyana, and Samadhi, the last three limbs of Patanjali’s eight limbs of yoga and is described and discussed in Chapter Three of the Yoga Sutras. Kofi Busia’s succinct translation of the first few sutras of this chapter may be of use to the reader who is unfamiliar with these terms.

“Concentration (Dharana) consists of keeping the attention centered in one area. Keeping the attention uninterrupted in that state is meditation (Dhyana.) Enlightenment (Samadhi) comes when the attention-keeping ability shines forth as an entity in its own right, quite separate from the means or objects first used to create or draw it forth. These three together are called insightful perception (Samyama). Achievement of it brings the very highest wisdom. It is used to discover higher and higher planes of wisdom.”

Mr. Iyengar’s discourse begins … “have peculiar qualities known as touch, form, sound, taste and smell. Our body is made up of these five elements with these five qualities of the elements; it comprises flesh, bones, bone marrow, blood, and so forth. Along with the five elements and five qualities of elements, each human has in their system to know five organs of action and five organs of perception. Legs, arms, excretory organs, generative organs and mouth are known as organs of action. Eyes, ears, nose, tongue and skin are known as organs of perception. The elements are felt by action from the organs of action. There is tremendous communication between the organs of action and the organs of perception. While performing the asanas, the flesh, the marrow of the bones and the bones are organs of action, The skin, the feeling, the smell, the touch, the vibration, the movements are all connected to the organs of perception.

While performing the asanas, you and I, we have to very carefully observe that if the muscles are extended strongly, heavily, or with speed, the organs of perception cannot receive the action done by the fibers, by the cells, by the spindles, or the muscles. Hence they do not receive the actual functioning of the inner system which can only imprint on the organs of perception – the skin – to be felt later by the other parts: the eyes, the ears. So, when performing the asanas, one has to be very careful. The spindles of the physical elemental system (the fibers of the muscles) should act so as to not disturb the fibers of the organs of perception, the inner layer of the skin. If they are not overstretched, naturally the organs of perception can receive the exact action done by the flesh. So when we are performing the asanas, we have to adjust in such a way that the fibers of the flesh do not protrude toward the skin more than what is essential.

(In making contact between the movement and the organs of perception, all the elements become involved.) The power of intelligence you use to make contact is the element of air flowing in the system. They call it bio-energy, we call it prana. The will, the mind that you use, is the fire; the circulation which take place is connected to the element of water, and the mass of flesh within is nothing but the element of earth. And, while performing, as there is a pause between two sounds, a pause between two actions, as there is a space between two words, so also in the system there is an inner space, which is known as the element of ether.

When the asanas are performed, the power of intelligence, the element of air, should be spaced in such a way that the spindles of the organs of action, the flesh, allow the movement to come in contact with the spindles of the organs of perception, the inner layer of the skin. Then you understand the perfect balance of the presentation of that asana. If there is an overstretch, they are hard; you hit the organs of perception so strongly that they become insensitive. If there is an under-stretch there is no feeling; the organs of perception do not perceive the action. So when the organs of perception maintain their sensitivity, the fibers of the flesh, the organs of action have to be carefully handled inside, using the intelligence so that the fire, the mind, may not burn or move the fibers too fast or extinguish them.

And if you can do that way, than you know the contacting and balancing of the cells of the organs of perception through the cells of the organs of action; the ligaments, fibers and so forth. When they commune while performing, when you have understood the tremendous inner balance, without aggravating the organs of perception or of action, then you have mastered the asana. Only that asana! So the communication between the organs of perception and the organs of action should commune to the intelligence a certain rhythm and balance while performing. When that is performed, that asana is mastered. Sometimes we overstretch, sometimes we under-stretch, sometimes we use with will, sometimes we use the force of our body. These are known as imbalances in our presentations. When these are removed, the asana is perfect.

Now, there needs to be tremendous reflection because the elements have no reflection at all, they only act; but in acting they send a message to the organs of perception, triggering them to feel the essence of the action. In order to feel that, the organs of perception, which are connected to the brain, which is connected to the mind because the flesh is connected to the bone, and intelligence which is connected to the consciousness, must be intermingled to create the exact mixture, the exact blending of the fibers of the flesh with the fibers of the organs of perception. This requires tremendous repose, rethinking, reflection. Flesh acts, so it is a forward action from the flesh. Organs of perception should receive, should draw back. In order to draw back you have to create a pause, a space for the action, or the force of action which has been used, to be received by the organs of perception. That receiving movement is meditation in asana.

The acting movement requires skillful action. You have to create even more skillfulness to receive that skillful action with skillful organs of perception. That is why I said you have to communicate with each cell, with the air which is intelligence. So the intelligence acts as a bridge to bring the space, the ether, through vibration, sound, so that the organs of action and the organs of perception are brought very near,  without hitting each other. Each cell of the skin, while performing an asana, should exactly face level to the top layer of the flesh, or the cells of the flesh should be exactly facing the cell of the skin. One head of the spindle actually facing the other head of the spindle of the organs of perception. If that is done, that is known as integration, Samyama: that my cells of the body are completely one with the cells of the organs of perception. When the cells of action and the cells of perception have become one, the intelligence dissolves in those two, and makes these three vehicles of the consciousness as a single conscious movement in the entire body – this is samyama, or samadhi in that pose. I hope you understand – it is very difficult.”

without hitting each other. Each cell of the skin, while performing an asana, should exactly face level to the top layer of the flesh, or the cells of the flesh should be exactly facing the cell of the skin. One head of the spindle actually facing the other head of the spindle of the organs of perception. If that is done, that is known as integration, Samyama: that my cells of the body are completely one with the cells of the organs of perception. When the cells of action and the cells of perception have become one, the intelligence dissolves in those two, and makes these three vehicles of the consciousness as a single conscious movement in the entire body – this is samyama, or samadhi in that pose. I hope you understand – it is very difficult.”

Samyama in Asana: Part 2

You all know ‘samyama‘ (the simultaneous and sequential practice of dharana, dhyana and samadhi as described in chapter 3, the Vibhuti Pada of the Yoga Sutras) on one level or another, if you are practicing, as it is embedded in the nature of the organism to integrate intelligence, sensation and action. Driving a car is a simple and common example. The organs of action, ( hands on the steering wheel and gear shift, feet on the pedals), the organs of perception, (eyes and ears), and the intelligence, all act together as a single conscious process. As I have been teaching my 17 year old son how to drive, I fully appreciate that refining the art of driving is an ongoing process.

Same in mastery of the art of asana. Asana or posture is an on-going process of action, perception and intelligent inquiry. This is a point often missed in the modern approach to teaching asana where there are non-stop ‘acting’ instructions and no pausing to ‘reflect’ or receive the effects of the action. Iyengar spent years practicing vinyasa style yoga with his teacher (and brother-in-law) Krishnamacharya, refining his ability to move effortlessly, before he matured into his style of experiencing every pose as a meditative pose. There is tremendous elegance and artistry to be felt and expressed in movement, but samyama is different because of the stillness required. Maturity, patience, persistence and total openness are needed on this inner journey of awakening.

You already know this. In your practice just relax, be the ‘Seer’, and ‘See’ what is happening. Step one is to tap into the energy flow and sustain your attention here. (Not always easy as we all begin with some level of Attention Deficit Disorder.) For beginners, it is the outer breath. More experienced students realize that all energy is breath, aka prana or chi. Second step is to find the yin/yang, the dvandvas, a positive – negative polarity around which you can follow the ebb and flow of energy. Allow this polarity to find balance. This may take some time as well. Be patient. Third, drop the psychological content. ‘Drop it’ does not mean ‘stop it.’ Just let it be, without holding on to it, and continue to return to and sustain your attention to the physiological energy flow. This stage feels a bit like snorkeling or scuba diving as you are moving into the inner world of water, waves and other fluid movements.

Now, find the center or still point, the fulcrum around which the pair of energies oscillate in equilibrium. Rest in that center and continue to “drop everything”. All that remains is infinity, the luminous emptiness, Pure Awareness, that is the Source of all movement/activity. Rest in the silence. You may get a micro-second glance or longer before your attention is pulled back to the physiological or psychological activity. Not to worry. It is all process. Start again with bringing your attention to the energy flow. This is dharana. Staying there with your attention is dhyana. Relaxing into this state is samadhi, and the continuous cycling through the steps is samyama. Forever. The seeds of awakening will germinate and grow as you practice with awareness and sensitivity.

Remember that the ‘Silence’ referred to here does not require the absence of mind activity but a shift in attention from what is moving to the ever-present silence. Just as the experience of “Now” does not require ‘stopping’ time, tasting the silence does not require forcing the mind into stillness, which is essentially impossible. Just notice that ‘Silence’ is ever-present, whatever may arise. Awareness or Presence are other words people use to point to this. It is only habit that keeps us from resting in our own stillness, (drashtuh svarupe avasthanam).

Although your own direct experience is the most crucial aspect in making sense of Mr. Iyengar’s discourse on “Samyama in Asana”, some background information on the Samkhya model of reality can be very helpful as the term samyama comes directly from Patanjali. The meditative journey to awakening as articulated in his  Yoga Sutras uses the principles of Samkhya as the primary road map. Not quite as simple Taoism, it has 25 elements rather than two. These 25 are not abstract concepts but living qualities to be experienced, tasted, felt and studied. Consider this as a map to help you navigate your direct experience of the energetic reality. If you break the 25 into 5 groups of five, the whole model becomes much easier to digest.

Yoga Sutras uses the principles of Samkhya as the primary road map. Not quite as simple Taoism, it has 25 elements rather than two. These 25 are not abstract concepts but living qualities to be experienced, tasted, felt and studied. Consider this as a map to help you navigate your direct experience of the energetic reality. If you break the 25 into 5 groups of five, the whole model becomes much easier to digest.

The first five begins with the primary two, Purusha and Prakriti. They are foundational, sort of like the yin and yang principles of Taoism, and are at the root all of the sutras. Purusha can be seen as the masculine or yang  expression of spirituality, the formless, unchanging, unbounded, and unlimited ‘Seer’, often described as ‘Soul’ in western spiritual writings. Prakriti would then be the yin, the feminine, the world of unlimited forms, the ‘Seen’; of birth and death and all modes of change. Spirit is often used in the west to describe this manifest dimension of spirituality.

expression of spirituality, the formless, unchanging, unbounded, and unlimited ‘Seer’, often described as ‘Soul’ in western spiritual writings. Prakriti would then be the yin, the feminine, the world of unlimited forms, the ‘Seen’; of birth and death and all modes of change. Spirit is often used in the west to describe this manifest dimension of spirituality.

Enlightenment, in the Yoga Sutras, involves differentiation or discrimination between Purusha and Prakriti, the Seer and the Seen, and the realization that the Self, the “I” is the unchanging luminous “Seer”, Purusha, and not the mental constructs created by the mind, which are in the realm of prakriti. (Samkhya sees prakriti as separate from Purusha, enlightenment requires isolation from Prakriti, and thus is a dualistic philosophy. Modern spiritual understanding sees the limitation (and masculine bias!) of this perspective and recognizes that the world of forms, the feminine shakti/prakriti is never separate from the formless. Integral spirituality, (and Vedanta) honors both aspects of creation equally.)

Patanjali introduces enlightenment immediately in his Yoga Sutras. In the Samadhi Pada, chapter 1,  he says:

he says:

I-2 yogash citta vrtti nirodhah:

Yoga is the resolution of the (dysfunctional) mind states.

I-3 tada drashtuh svarupe avasthanam:

Then the identity of the Self (I am) with pure Awareness becomes stable.

I-4 vrtti sarupyam itaratra:

(At other times, i.e., in dysfunctional mind states) mind activity is mistaken for the Self.

The notion of ‘identification’, who or what am I, is introduced and enlightenment here is described as clearly recognizing that the true nature of I, of ‘I am’ is the infinite, unbounded Purusha, and this recognition becomes stabilized over time. Mind activity (prakriti), the basis of all experience is not the ‘Self’. Anything that is limited or transient cannot be the ‘Self’. That leaves only Purusha.

We all get tastes of this, usually without realizing what is happening, when we are at peace with ourselves in the moment, or when the self-sense temporarily drops away. Being in nature can facilitate this dropping away of “self”, as can a heart centered relational experience with another being. My teacher Swami Dayananda uses humor and jokes to get students to laugh. In laughter one forgets the psychological drama for a moment and dwells in the bliss of delight. These ‘dropping away’ states are usually temporary and the voices of the egoic selves inevitably return.These ‘egoic selves’ are based on the beliefs that ‘I am limited’, I need to be redeemed, or saved; that something has to change for me to be whole or free. But hopefully, if we can begin to recognize that ‘enlightenment’ is just realizing what is always ever – present anyway, that our natural state is happiness. Then perhaps we can relax a bit more and not turn practice into struggle.

Prakriti is the source of the other 23 principles, all based in form and thus subject to change. The next three (along with Purusha and Prakriti completing the first pentad) comprise what might be called in English, the ‘mind’. Mahat/Buddhi is the first evolute of prakriti. Mahat is cosmic intelligence, the mind of the universe that organizes and guides the world of form. It’s human expression is called the “Buddhi” and is the aspect of mind that integrates the various components of the human. The buddhi is also the discriminator, the gateway to self-realization. Buddha, the ‘awakened one’ is one whose buddhi is awake and fully integrated into the human functioning.

Ahamkara, the “I” maker, creates a personality/ego/self-identity. This delightful aspect of mind first appears in the human around the age of two when I, me and mine come to dominate the child’s world view. The ahamkara is essential for healthy mental functioning and navigating relationships, but is not capable of ‘seeing’ more subtle aspects of consciousness. That role belongs to the buddhi, if and when it is awake! This is the basic point Patanjali makes in the first few sutras.

Manas is the third aspect of the mental trinity. It involves memory and habits, and organizes sensory information so that it is intelligible to the buddhi. Operating on ‘autopilot’ is manas in action. Living in the present moment, and choosing carefully and consciously, is the buddhi in action.

The next 20 principles can be explored in groups of five and revolve around another yin/yang polarity, action and perception. There are five organs of action, aspects of the human organism that act in the world, and five gross elements that carry forth the action of the organs of action. There are also five organs of perception and five subtle elements that commune with the organs of perception. The integration of action, perception and the intelligence, the buddhi, is the theme of Samyama in Asana. The manas and ahamkara remain in the background performing their functions, but not intruding inappropriately in the process. Inappropriate intrusion of the ahamkara might include the personalization of the ongoing experience. ‘I don’t like this’, I’m not very good’, ‘look at me’ are just a few of the comments possible. Inappropriate manas would look like the continuous repetition of old habits that keep the mind/body stuck in patterns of suffering.

The five gross elements, the basic constituents of creation, are earth, water, fire, air and ether. The Chinese, (but interestingly enough, not the Japanese,) substitute wood and metal for air and ether.) These are the most tangible, palpable aspects of reality and the ones we meet first in the body.

Earth is weight or mass.  It is where we meet gravity directly and is the source of stability, the sthira of sthira sukham asanam. From one point of view, some of the qualities of earth are solid, dense, and cold. Feel this weightiness as the magnetic pull of the earth. Earth is associated with the 1st or root chakra, the muladhara, and the sense of smell, the most primal of our 5 senses.

It is where we meet gravity directly and is the source of stability, the sthira of sthira sukham asanam. From one point of view, some of the qualities of earth are solid, dense, and cold. Feel this weightiness as the magnetic pull of the earth. Earth is associated with the 1st or root chakra, the muladhara, and the sense of smell, the most primal of our 5 senses.

Water has weight, is tangible, but has the additional qualities of mobility and flexibility. It flows, it dissolves, it carries power in its mobility. It allows life to flourish. We are watery creatures walking about on land, carrying the ocean inside of us. Feel this. Feel like you are on a surf board, anchored, but free to ride the waves. Water is associated with the second chakra at the sacral region and the sense of taste.

Fire is the third element, expressed at the third chakra, the solar plexus. Connected to digestion, the fire of burning the fuel of food, the element fire is felt as warmth of the body. We are warm blooded creatures . Fire also represents dynamic action, passion, burning desire: and, at times, anger. Fire balances water. Iyengar describes them as anti elements. Too much fire and the water disappears into air. Too much water and the fire is extinguished. Finding balance here is primary. We can also see water and fire emotionally, as parasympathetic/relaxing/cooling and sympathetic/fiery arousal. People with a pitta constitution in Ayurveda have a strong fire element.

Air is the gaseous state of matter, often referred to as ‘wind’. The five pranas are aspects of the element air as experienced in the ‘breath’. Air also refers to communication, as in the nervous system. Mercury, the messenger of the gods, rules Gemini, an air sign in astrology. Air is associated with the fourth chakra at the heart.

There is no good equivalent to the fifth element, akasha. The closest is space or spaciousness. It refers to the aspect of creation that contains all other aspects. Einstein would agree, as he recognized that space, as described in physics, is subject to change. It is not fixed or absolute, which was the belief in science for centuries. This is still not an easy concept to grasp, but we all can experience the felt sense of having space, or needing more space, or expanding in to spaciousness.

The five organs of action are: arms, legs, excretory organs, generative or sexual organs and mouth. These are physical, tangible vehicles that allow us to interact with the world. I yoga practice we train arms and legs to help move and support the body. Certain asanas, ( as well as sensible dietary choices!) help the excretory organs to function in a healthy manner. Ayurveda considers that disease often begins with poor elimination. The sex organs have much hormonal/physiological/emotional power which also must be utilized intelligently. The mouth is the source of both speaking and eating. Wise speech is an important aspect of an intelligent and compassionate life.

The five organs of perception are: eyes, ears, nose, tongue and skin and the subtle elements that accompany them are sight, sound, smell, taste and touch. In asana, the skin is the primary organ of perception. Related to skin as tactile sensors are the nerve endings in the joints and tendons that respond to pressure and tension, and the inner ears for balance and coordination. Information coming from within the body is fed to the intelligence, the buddhi and adjustments are made by moving bones, redirecting energy flow, until there is a dynamic, self sustaining stability in the posture. This is sthira sukham, this is samyama in asana. Over time, the energy lines stabilize and the connective tissue pathways become charged with aliveness. The blood vessels, nerves and muscle fibers all listen to the energies traveling along the expanding fascial highways and respond as a single intelligence, moment to moment, adapting the needs as they change. this is the awakening of the intelligence of the body that is cultivated in samyama. (In a baby first learning to sit, stand and walk, the information flow to the movement brain (cerebellum and parts of the cortex) happens instinctively and the child’s attention is absorbed by learning to move. No thought or analysis is needed. However this process is soon overridden by the need to acquire language and manage the other cultural and egoic demands. This somatic intelligence tends to fade into the background. Some aspects may be employed in learning specific movement skills such as athletics or dance, but only asana explores the whole process for its own sake. )