Lesson 12: The Science of Breath

1. Anatomy and Kinesiology of Breathing.

Breathing is the most fundamental movement of energy in the body as it unites us to the world around us continuously and intimately. Our words spiritual and spirit come from the Latin ‘spiritus’ meaning breath, giving us insight into the layers of importance embedded in this rhythmic flow of inhalation and exhalation. Life begins with our first breath and ends with our last, and every breath is spiritually important.

In the first section, we began our observation of our breathing, and this will continue to be our primary practice. Just watching and feeling. But now we can add some specific directions to help focus our attention what is happening at the structural level. Returning to our supported savasana,  allow the spine to relax as fully as possible and begin to notice what parts of the body actually move with the breathing. Most people will feel the belly or abdomen moving up and down, especially as the relaxation deepens.

allow the spine to relax as fully as possible and begin to notice what parts of the body actually move with the breathing. Most people will feel the belly or abdomen moving up and down, especially as the relaxation deepens.

With ‘abdominal breathing, the diaphragm pushes down toward the abdomen on inhalation, causing it to rise up. On the exhalation, the abdomen drops and the diaphragm returns back up in the chest as the air is expelled. For those who carry a lot of anxiety or tension, this is a powerful way to relax the diaphragm and calm the mind. Can you now feel the diaphragm? It is easy to feel the abdomen, as you can see it move. The diaphragm is hidden from view, and often from perception. Visualize the picture of the diaphragm above. See its rounded, dome like shape as it fills the lower rib cage. Imagine the muscle fibers lengthening. In the second image, we see the diaphragm from below. The white tendinous fibers in the center are attachments for the muscle fibers, which also attach to the surrounding ribs.

How do the muscle fibers of the diaphragm act? We can look at the biceps muscle for some clues.  In a push up, the hand and lower arm are the stabilizing end, and the contracting biceps pulls the upper arm toward the forearm.

In a push up, the hand and lower arm are the stabilizing end, and the contracting biceps pulls the upper arm toward the forearm.  In a curl, the opposite action occurs. The upper arm is the stable end and the forearm is pulled toward the upper arm. Muscles have no inherent preference in direction of pull. It just depends on which end is the stabilizer and which is the mover.

In a curl, the opposite action occurs. The upper arm is the stable end and the forearm is pulled toward the upper arm. Muscles have no inherent preference in direction of pull. It just depends on which end is the stabilizer and which is the mover.

The same principle is seen in the diaphragm, a large muscle, with one end attaching to the ribs and the other end to its own central tendon, (which makes the diaphragm unique). In the diaphragm, most people (unconsciously) stabilize the ribs and the muscle fibers pull the tendon down on contraction, which in breathing is inhalation. In exhalation, the fibers relax and the tendon rises back up. The freeing up of this action is called abdominal breathing, as mentioned above. The distance moved by the diaphragm is called the ‘excursion’ and averages 3 – 5 centimeters. A well trained, healthy diaphragm can move as much as 7 – 8 cms.

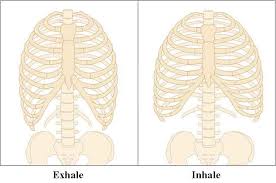

Another possibility, explored in yogic breathing, involves stabilizing the tendon and using the muscle fibers to lift the ribs. On inhalation, when the muscles contract, they pull the ribs up, and because of the way the ribs move on the spine, the ribs also flare out. On the exhalation, they reverse, dropping and coming back in. Same fibers working, just pulling in the opposite direction. In order to have this work, the ribs have to be free to move, and this is another area where yoga practice can help.

Another possibility, explored in yogic breathing, involves stabilizing the tendon and using the muscle fibers to lift the ribs. On inhalation, when the muscles contract, they pull the ribs up, and because of the way the ribs move on the spine, the ribs also flare out. On the exhalation, they reverse, dropping and coming back in. Same fibers working, just pulling in the opposite direction. In order to have this work, the ribs have to be free to move, and this is another area where yoga practice can help.

There is a physiological impulse inhale. When the oxygen/carbon dioxide levels reach a limit, a signalis sent along the phrenic nerve to the diaphragm telling it to contract. The relaxation of the contraction creates the exhalation. Because the average person does not exhale completely, over time, the fibers of the muscles relax less and less, growing tighter, decreasing the movement available to the diaphragm. This will be seen as a slow collapse of the chest and a bulging of the abdomen, having nothing to do with weight gain. That is another layer. This is strictly an energetic shift based on poor breathing patterns. Healthy exhalation helps to stretch the diaphragm, and the abdominal muscles are a big help here.

The abs that most interest us are the transversus abdomini, the deepest of the three layers, the others being the rectus abdomeni and the internal and external obliques. The transversus runs at right angles to the spine and knits together at the median line, the linea alba, (white line) which runs right up the center. We will look at this from a radically different perspective when we take up Chinese medicine in a later section, but for now know that the transversus works in synchrony with the multifidus muscles deep in the posterior spine, to help maintain an integrated core support. (see Tonic Function’ section).

When the transversus is strong, it supports the core without shortening it and provides a powerful rebound to deepen the exhalation. It thus acts as a  counterbalance to the contracting diaphragm. In the practice of uddiyana bandha, the whole abdominal wall is drawn in and lifted to maximize the stretch of the diaphragm and the expulsion of air from the lungs. The multifidi also have to participate to release the spine, so a full uddiyana may be difficult with spinal knots. Mild practice tones the abdominal wall without strain.

counterbalance to the contracting diaphragm. In the practice of uddiyana bandha, the whole abdominal wall is drawn in and lifted to maximize the stretch of the diaphragm and the expulsion of air from the lungs. The multifidi also have to participate to release the spine, so a full uddiyana may be difficult with spinal knots. Mild practice tones the abdominal wall without strain.

2. Circulation of the Prana/Chi

The hidden breath is the circulation of the energies of the breath throughout the body and the respiration at the cellular level.

(to be continued…)